A Far Country

South Australia, 1846, and the countryside is being rapidly carved into pastures and copper mines. It’s first come, first served and no prizes for coming second. But to hold your prize you must be as tough and unforgiving as the land itself.

A young man, Jason Hallam, shipwrecked off the Yorke Peninsula, is taken in by the Narungga clan who live there. He learns their ways, hears the whispers that the kuinyo, the white man is coming to take their land. And then black and white tragically collide.

Jason is caught between two worlds — his best friend, Mura, is Narungga, and Alison, the girl he loves, a grazier’s daughter. What price is he prepared to pay to tread his own path, make his own rules?

A compelling story of loyalty, loss and survival, A Far Country is alive with the beauty and brutality of a wild frontier and the people who made it their home.

To Luke, who missed out last time, and to Stefan, who kindly gave me the use of his name

CONTENTS

About A Far Country

Dedication

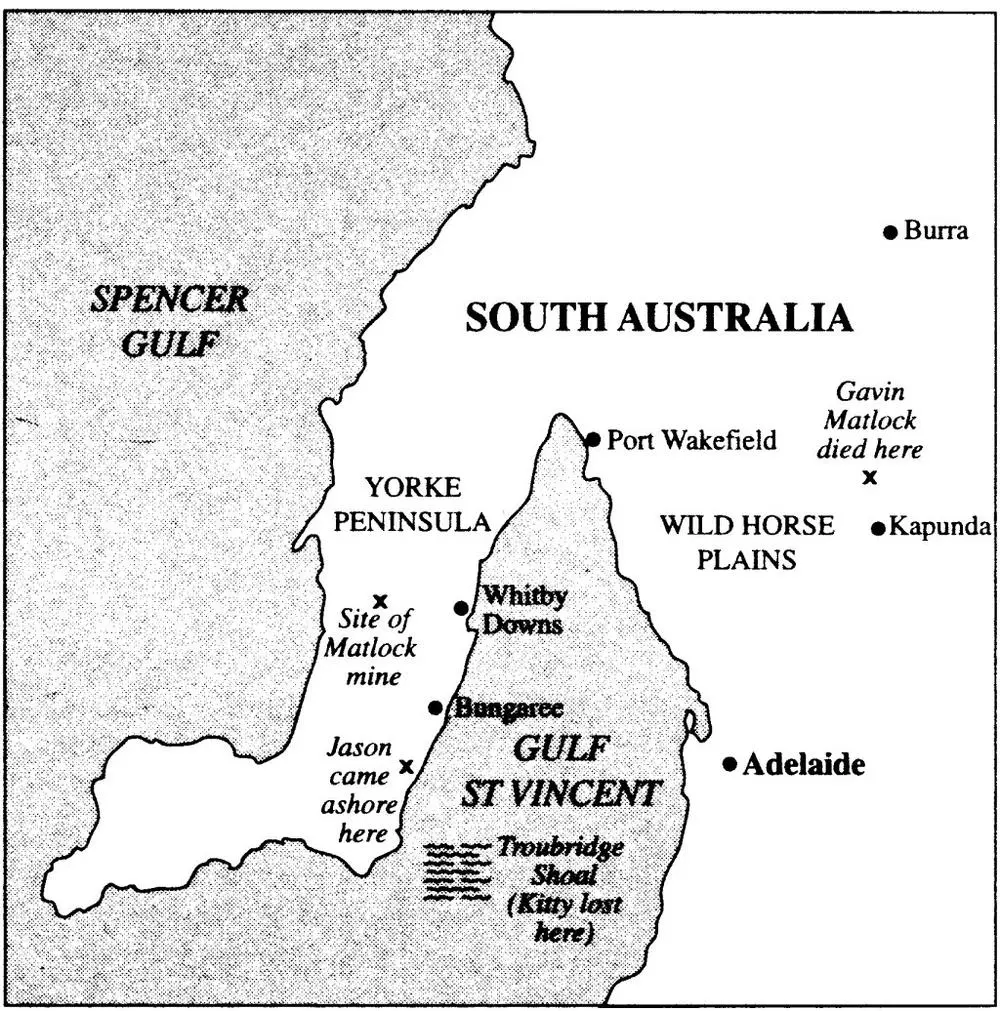

Map

PROLOGUE

BOOK ONE: PETREL

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

BOOK TWO: STORM HAWK

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

BOOK THREE: EAGLES

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

EPILOGUE

AUTHOR’S NOTES

About John Fletcher

Also by the Author

Copyright

I am in torment, therefore I shall go today to the place where it happened.

If Gavin knew he would prohibit it for fear it might upset me too much or—far worse—for fear it might not upset me at all.

He has always believed that he knows what is good for me, what is bad for me. He has always been sure of that, as of everything. At least he had been until now, until the death of Edward Erhart Matlock, our son, aged fourteen. I do not normally take issue with my husband but today is different. It is not every day, after all, that one mourns the loss of one’s only child.

Gavin is afraid for me, what I may do or not do. I see it in his eyes. He no longer knows me. He is a big man, hard and on occasion pitiless, as he must be if he is to have any chance of subduing this hard and pitiless land. When he heard the news of our son’s death he screamed his hurt like a baby, hands like hammers punishing the earth. He is incapable of understanding that my own sorrow is no less real for being hidden. Most women show their feelings and it offends his sense of propriety that I do not. I cannot do it. My grief is in my blood and marrow and bone, too deeply rooted to find expression in the tears and keening he expects. I see him watching my dry eyes, my face and voice without evidence of grief. He thinks I am cold.

I cannot help what he thinks.

All the same, it angers me. How can he think such things? He has known me seventeen years yet it is plain that he understands nothing of me, has never understood. This realisation shocks me. I am watching him—a person whom I thought as much a part of me as my breath and blood, a sharer in my fears, my joys, in eating and sleeping and loving—become a stranger before my eyes.

Death has taken more than the breath and bone and skin, the joy and hope that was our son. So be it. I have survived everything else that life has brought me. I shall survive this.

As soon as Gavin has left the house—it seems obscene that the daily work must continue despite death and grief, yet how can it be otherwise?—I shall go to the place where Edward died. I shall go alone. I shall say my farewells to my son in my own way. He will understand why my grief is hidden. He will not question it, he to whom all knowledge and all secrets are now revealed.

II

The peninsula runs from north-east to south-west.

1 comment