That is true, says the first Man, for he was not a Man presumptuously secure, but had escap’d a long while, and Men, as I said above, especially in the City, began to be overeasie upon that Score. That is true, says he, I do not think my self secure, but I hope I have not been in Company with any Person that there has been any Danger in. No! Says his Neighbour, was not you at the Bull-head Tavern in Gracechurch Street with Mr. —— the Night before last: YES, says the first, I was, but there was, but there was no Body there, that we had any Reason to think dangerous: Upon which his Neighbour said no more, being unwilling to surprize him; but this made him more inquisitive, and as his Neighbour appear’d backward, he was the more impatient, and in a kind of Warmth, says he aloud, why he is not dead, is he! upon which his Neighbour still was silent, but cast up his Eyes, and said something to himself; at which the first Citizen turned pale, and said no more but this, then I am a dead Man too, and went Home immediately, and sent for a neighbouring Apothecary to give him something preventive, for he had not yet found himself ill; but the Apothecary opening his Breast, fetch’d a Sigh, and said no more, but this, look up to God; and the Man died in a few Hours.

Now let any Man judge from a Case like this, if it is possible for the Regulations of Magistrates, either by shutting up the Sick, or removing them, to stop an Infection, which spreads it self from Man to Man, even while they are perfectly well, and insensible of its Approach, and may be so for many Days.

It may be proper to ask here, how long it may be supposed, Men might have the Seeds of the Contagion in them, before it discover’d it self in this fatal Manner; and how long they might go about seemingly whole, and yet be contagious to all those that came near them? I believe the most experienc’d Physicians cannot answer this Question directly, any more than I can; and something an ordinary Observer may take notice of, which may pass their Observation. The opinion of Physicians Abroad seems to be, that it may lye Dormant in the Spirits, or in the Blood Vessels, a very considerable Time; why else do they exact a Quarentine of those who come into their Harbours, and Ports, from suspected Places? Forty Days is, one would think, too long for Nature to struggle with such an Enemy as this, and not conquer it, or yield to it: But I could not think by my own Observation that they can be infected so, as to be contagious to others, above fifteen or sixteen Days at farthest; and on that score it was, that when a House was shut up in the City, and any one had died of the Plague, but no Body appear’d to be ill in the Family for sixteen or eighteen Days after, they were not so strict, but that they would connive at their going privately Abroad; nor would People be much afraid of them afterward, but rather think they were fortified the better, having not been vulnerable when the Enemy was in their own House; but we sometimes found it had lyen much longer conceal’d.

Upon the foot of all these Observations, I must say, that tho’ Providence seem’d to direct my Conduct to be otherwise; yet it is my opinion, and I must leave it as a Prescription, (viz.) that the best Physick against the Plague is to run away from it. I know People encourage themselves, by saying, God is able to keep us in the midst of Danger, and able to overtake us when we think our selves out of Danger; and this kept Thousands in the Town, whose Carcasses went into the great Pits by Cart Loads; and who, if they had fled from the Danger, had, I believe, been safe from the Disaster; at least ’tis probable they had been safe.

And were this very Fundamental only duly consider’d by the People, on any future occasion of this, or the like Nature, I am persuaded it would put them upon quite different Measures for managing the People, from those that they took in 1665, or than any that have been taken Abroad that I have heard of; in a Word, they would consider of separating the People into smaller Bodies, and removing them in Time farther from one another, and not let such a Contagion as this, which is indeed chiefly dangerous to collected Bodies of People, find a Million of People in a Body together, as was very near the Case before, and would certainly be the Case, if it should ever appear again.

The Plague like a great Fire, if a few Houses only are contiguous where it happens, can only burn a few Houses; or if it begins in a single, or as we call it a lone House, can only burn that lone House where it begins: But if it begins in a close built Town, or City, and gets a Head, there its Fury encreases, it rages over the whole Place, and consumes all it can reach.

I could propose many Schemes, on the foot of which the Government of this City, if ever they should be under the Apprehensions of such another Enemy, (God forbid they should) might ease themselves of the greatest Part of the dangerous People that belong to them; I mean such as the begging, starving, labouring Poor, and among them chiefly those who in Case of a Siege, are call’d the useless Mouths; who being then prudently, and to their own Advantage dispos’d of, and the wealthy Inhabitants disposing of themselves, and of their Servants, and Children, the City and its adjacent Parts would be so effectually evacuated, that there would not be above a tenth Part of its People left together, for the Disease to take hold upon: But suppose them to be a fifth Part, and that two Hundred and fifty Thousand People were left, and if it did seize upon them, they would by their living so much at large, be much better prepar’d to defend themselves against the Infection, and be less liable to the Effects of it, than if the same Number of People lived close together in one smaller City, such as Dublin, or Amsterdam, or the like.

It is true, Hundreds, yea Thousands of Families fled away at this last Plague, but then of them, many fled too late, and not only died in their Flight, but carried the Distemper with them into the Countries where they went, and infected those whom they went among for Safety; which confounded the Thing, and made that be a Propagation of the Distemper, which was the best means to prevent it; and this too is an Evidence of it, and brings me back to what I only hinted at before, but must speak more fully to here; namely, that Men went about apparently well, many Days after they had the taint of the Disease in their Vitals, and after their Spirits were so seiz’d, as that they could never escape it; and that all the while they did so, they were dangerous to others. I say, this proves, that so it was; for such People infected the very Towns they went thro’, as well as the Families they went among, and it was by that means, that almost all the great Towns in England had the Distemper among them, more or less; and always they would tell you such a Londoner or such a Londoner brought it down.

It must not be omitted, that when I speak of those People who were really thus dangerous, I suppose them to be utterly ignorant of their own Condition, for if they really knew their Circumstances to be such as indeed they were, they must have been a kind of willful Murtherers, if they would have gone Abroad among healthy People, and it would have verified indeed the Suggestion which I mention’d above, and which I thought seemed untrue, (viz.) That the infected People were utterly careless as to giving the Infection to others, and rather forward to do it than not; and I believe it was partly from this very Thing that they raised that Suggestion, which I hope was not really true in Fact.

I confess no particular Case is sufficient to prove a general, but I cou’d name several People within the Knowledge of some of their Neighbours and Families yet living, who shew’d the contrary to an extream. One Man, a Master of a Family in my Neighbourhood, having had the Distemper, he thought he had it given him by a poor Workman whom he employ’d, and whom he went to his House to see, or went for some Work that he wanted to have finished, and he had some Apprehensions even while he was at the poor Workman’s Door, but did not discover it fully, but the next Day it discovered it self, and he was taken very ill; upon which he immediately caused himself to be carried into an out Building which he had in his Yard, and where there was a Chamber over a Work house, the Man being a Brazier; here he lay, and here he died, and would be tended by none of his Neighbours, but by a Nurse from Abroad, and would not suffer his Wife, or Children, or Servants, to come up into the Room lest they should be infected, but sent them his Blessing and Prayers for them by the Nurse, who spoke it to them at a Distance, and all this for fear of giving them the Distemper, and without which, he knew as they were kept up, they could not have it.

And here I must observe also, that the Plague, as I suppose all Distempers do, operated in a different Manner on differing Constitutions; some were immediately overwhelm’d with it, and it came to violent Fevers, Vomitings, unsufferable Head-achs, Pains in the Back, and so up to Ravings and Ragings with those Pains: Others with Swellings and Tumours in the Neck or Groyn, or Arm-pits, which till they could be broke, put them into insufferable Agonies and Torment; while others, as I have observ’d, were silently infected, the Fever preying upon their Spirits insensibly, and they seeing little of it, till they fell into swooning, and faintings, and Death without pain.

I am not Physician enough to enter into the particular Reasons and Manner of these differing Effects of one and the same Distemper, and of its differing Operation in several Bodies; nor is it my Business here to record the Observations, which I really made, because the Doctors themselves, have done that part much more effectually than I can do, and because my opinion may in some things differ from theirs: I am only relating what I know, or have heard, or believe of the particular Cases, and what fell within the Compass of my View, and the different Nature of the Infection, as it appeared in the particular Cases which I have related; but this may be added too, that tho’ the former Sort of those Cases, namely those openly visited, were the worst for themselves as to Pain, I mean those that had such Fevers, Vomitings, Headachs, Pains and Swellings, because they died in such a dreadful Manner, yet the latter had the worst State of the Disease; for in the former they frequently recover’d, especially if the Swellings broke,* but the latter was inevitable Death; no cure, no help cou’d be possible, nothing could follow but Death; and it was worse also to others, because as, above, it secretly, and unperceiv’d by others, or by themselves, communicated Death to those they convers’d with, the penetrating Poison insinuating it self into their Blood in a Manner, which it is impossible to describe, or indeed conceive.

This infecting and being infected, without so much as its being known to either Person, is evident from two Sorts of Cases, which frequently happened at that Time; and there is hardly any Body living who was in London during the Infection, but must have known several of the Cases of both Sorts.

1. Fathers and Mothers have gone about as if they had been well, and have believ’d themselves to be so, till they have insensibly infected, and been the Destruction of their whole Families: Which they would have been far from doing, if they had the least Apprehensions of their being unsound and dangerous themselves. A Family, whose Story I have heard, was thus infected by the Father, and the Distemper began to appear upon some of them, even before he found it upon himself; but searching more narrowly, it appear’d he had been infected some Time, and as soon as he found that his Family had been poison’d by himself, he went distracted, and would have laid violent Hands upon himself, but was kept from that by those who look’d to him, and in a few Days died.

2. The other Particular is, that many People having been well to the best of their own Judgment, or by the best Observation which they could make of themselves for several Days, and only finding a Decay of Appetite, or a light Sickness upon their Stomachs; nay, some whose Appetite had been strong, and even craving, and only a light Pain in their Heads; have sent for Physicians to know what ail’d them, and have been found to their great Surprize, at the brink of Death, the Tokens upon them, or the Plague grown up to an incurable Height.

It was very sad to reflect, how such a Person as this last mentioned above, had been a walking Destroyer, perhaps for a Week or Fortnight before that; how he had ruin’d those, that he would have hazarded his Life to save, and had been breathing Death upon them, even perhaps in his tender Kissing and Embracings of his own Children: Yet thus certainly it was, and often has been, and I cou’d give many particular Cases where it has been so; if then the Blow is thus insensibly striking, if the Arrow flies thus unseen, and cannot be discovered; to what purpose are all the Schemes for shutting up or removing the sick People? those Schemes cannot take place, but upon those that appear to be sick, or to be infected; whereas there are among them, at the same time, Thousands of People, who seem to be well, but are all that while carrying Death with them into all Companies which they come into.

This frequently puzzled our Physicians, and especially the Apothecaries and Surgeons, who knew not how to discover the Sick from the Sound; they all allow’d that it was really so, that many People had the Plague in their very Blood, and preying upon their Spirits, and were in themselves but walking putrified Carcasses, whose Breath was infectious,* and their Sweat Poison; and yet were as well to look on as other People, and even knew it not themselves: I say, they all allowed that it was really true in Fact, but they knew not how to propose a Discovery.

My Friend Doctor Heath was of Opinion, that it might be known by the smell of their Breath; but then, as he said, who durst Smell to that Breath for his Information? Since to know it, he must draw the Stench of the Plague up into his own Brain, in order to distinguish the Smell! I have heard, it was the opinion of others, that it might be distinguish’d by the Party’s breathing upon a piece of Glass, where the Breath condensing, there might living Creatures be seen by a Microscope of strange monstrous and frightful Shapes, such as Dragons, Snakes, Serpents, and Devils, horrible to behold: But this I very much question the Truth of, and we had no Microscopes* at that Time, as I remember, to make the Experiment with.

It was the opinion also of another learned Man, that the Breath of such a Person would poison, and instantly kill a Bird; not only a small Bird, but even a Cock or Hen, and that if it did not immediately kill the latter, it would cause them to be roupy as they call it; particularly that if they had laid any Eggs at that Time, they would be all rotten: But those are Opinions which I never found supported by any Experiments, or heard of others that had seen it; so I leave them as I find them, only with this Remark; namely, that I think the Probabilities are very strong for them.

Some have proposed that such Persons should breathe hard upon warm Water, and that they would leave an unusual Scum upon it, or upon several other things, especially such as are of a glutinous Substance and are apt to receive a Scum and support it.

But from the whole I found, that the Nature of this Contagion was such, that it was impossible to discover it at all, or to prevent its spreading from one to another by any human Skill.

Here was indeed one Difficulty, which I could never thoroughly get over to this time, and which there is but one way of answering that I know of, and it is this, viz. The first Person that died of the Plague was in Decemb. 20th, or thereabouts 1664, and in, or about Long-acre, whence the first Person had the Infection, was generally said to be, from a Parcel of Silks imported from Holland, and first opened in that House.

But after this we heard no more of any Person dying of the Plague, or of the Distemper being in that Place, till the 9th of February; which was about 7 Weeks after, and then one more was buried out of the same House: Then it was hush’d, and we were perfectly easy as to the publick, for a great while; for there were no more entred in the Weekly Bill to be dead of the Plague, till the 22d of April, when there was 2 more buried not out of the same House, but out of the same Street; and as near as I can remember, it was out of the next House to the first: this was nine Weeks asunder, and after this we had No more till a Fortnight, and then it broke out in several Streets and spread every way. Now the Question seems to lye thus, where lay the Seeds of the Infection all this while? How came it to stop so long, and not stop any longer? Either the Distemper did not come immediately by Contagion from Body to Body, or if it did, then a Body may be capable to continue infected, without the Disease discovering itself, many Days, nay Weeks together, even not a Quarantine of Days only, but Soixantine, not only 40 Days but 60 Days or longer.

It’s true, there was, as I observed at first, and is well known to many yet living, a very cold Winter, and a long Frost,* which continued three Months, and this, the Doctors say, might check the Infection; but then the learned must allow me to say, that if according to their Notion, the Disease was, as I may say, only frozen up, it would like a frozen River, have returned to its usual Force and Current when it thaw’d, whereas the principal Recess of this Infection, which was from February to April, was after the Frost was broken, and the Weather mild and warm.

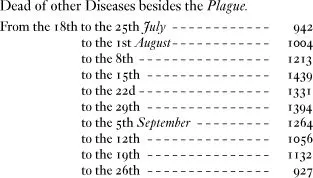

But there is another way of solving all this Difficulty, which I think my own Remembrance of the thing will supply; and that is, the Fact is not granted, namely, that there died none in those long Intervals, viz. from the 20th of December to the 9th of February, and from thence to the 22d of April. The Weekly Bills are the only Evidence on the other side, and those Bills were not of Credit enough, at least with me, to support an Hypothesis, or determine a Question of such Importance as this: For it was our receiv’d Opinion at that time, and I believe upon very good Grounds, that the Fraud lay in the Parish Officers, Searchers, and Persons appointed to give Account of the Dead, and what Diseases they died of: And as People were very loth at first to have the Neighbours believe their Houses were infected, so they gave Money to procure, or otherwise procur’d the dead Persons to be return’d as dying of other Distempers; and this I know was practis’d afterwards in many Places, I believe I might say in all Places, where the Distemper came, as will be seen by the vast Encrease of the Numbers plac’d in the Weekly Bills under other Articles of Diseases, during the time of the Infection: For Example, in the Month of July and August, when the Plague was coming on to its highest Pitch; it was very ordinary to have from a thousand to twelve hundred, nay to almost fifteen Hundred a Week of other Distempers; not that the Numbers of those Distempers were really encreased to such a Degree: But the great Number of Families and Houses where really the Infection was, obtain’d the Favour to have their dead be return’d of other Distempers to prevent the shutting up their Houses. For Example,

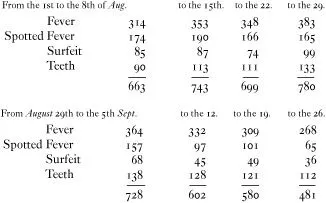

Now it was not doubted, but the greatest part of these, or a great part of them, were dead of the Plague, but the Officers were prevail’d with to return them as above, and the Numbers of some particular Articles of Distempers discover’d is, as follows;

There were several other Articles which bare a Proportion to these, and which it is easy to perceive, were increased on the same Account, as Aged, Consumptions, Vomitings, Imposthumes, Gripes, and the like, many of which were not doubted to be infected People; but as it was of the utmost Consequence to Families not to be known to be infected, if it was possible to avoid it, so they took all the measures they could to have it not believ’d; and if any died in their Houses to get them return’d to the Examiners, and by the Searchers, as having died of other Distempers.

This, I say, will account for the long Interval, which, as I have said, was between the dying of the first Persons that were returned in the Bill to be dead of the Plague, and the time when the Distemper spread openly, and could not be conceal’d.

Besides, the Weekly Bills themselves at that time evidently discover this Truth; for while there was no Mention of the Plague, and no Increase after it had been mentioned, yet it was apparent that there was an Encrease of those Distempers which bordered nearest upon it, for Example there were Eight, Twelve, Seventeen of the Spotted Fever in a Week, when there were none, or but very few of the Plague; whereas before One, Three, or Four, were the ordinary Weekly Numbers of that Distemper; likewise, as I observed before, the Burials increased Weekly in that particular Parish, and the Parishes adjacent, more than in any other Parish, altho’ there were none set down of the Plague; all which tells us, that the Infection was handed on, and the Succession of the Distemper really preserv’d, tho’ it seem’d to us at that time to be ceased, and to come again in a manner surprising.

It might be also, that the Infection might remain in other parts of the same Parcel of Goods which at first it came in, and which might not be perhaps opened, or at least not fully, or in the Cloths of the first infected Person; for I cannot think, that any Body could be seiz’d with the Contagion in a fatal and mortal Degree for nine Weeks together, and support his State of Health so well, as even not to discover it to themselves; yet if it were so, the Argument is the stronger in Favour of what I am saying; namely, that the Infection is retain’d in Bodies apparently well, and convey’d from them to those they converse with, while it is known to neither the one nor the other.

Great were the Confusions at that time upon this very Account; and when People began to be convinc’d that the Infection was receiv’d in this surprising manner from Persons apparently well, they began to be exceeding shie and jealous of every one that came near them. Once in a publick Day, whether a Sabbath Day or not I do not remember, in Aldgate Church in a Pew full of People, on a sudden, one fancy’d she smelt an ill Smell, immediately she fancies the Plague was in the Pew, whispers her Notion or Suspicion to the next, then rises and goes out of the Pew, it immediately took with the next, and so to them all; and every one of them, and of the two or three adjoining Pews, got up and went out of the Church, no Body knowing what it was offended them or from whom.

This immediately filled every Bodies Mouths with one Preparation or other, such as the old Women directed, and some perhaps as Physicians directed, in order to prevent Infection by the Breath of others; insomuch that if we came to go into a Church, when it was any thing full of People, there would be such a Mixture of Smells at the Entrance, that it was much more strong, tho’ perhaps not so wholesome, than if you were going into an Apothecary’s or Druggist’s Shop; in a Word, the whole Church was like a smelling Bottle, in one Corner it was all Perfumes, in another Aromaticks, Balsamicks, and Variety of Drugs, and Herbs; in another Salts and Spirits, as every one was furnish’d for their own Preservation; yet I observ’d, that after People were possess’d, as I have said, with the Belief or rather Assurance, of the Infection being thus carryed on by Persons apparently in Health, the Churches and Meeting-Houses were much thinner of People than at other times before that they us’d to be; for this is to be said of the People of London, that during the whole time of the Pestilence, the Churches or Meetings were never wholly shut up, nor did the People decline coming out to the public Worship of God, except only in some Parishes when the Violence of the Distemper was more particularly in that Parish at that time; and even then no longer, than it continued to be so.

Indeed nothing was more strange, than to see with what Courage the People went to the public Service of God, even at that time when they were afraid to stir out of their own Houses upon any other Occasion; this I mean before the time of Desperation, which I have mention’d already; this was a Proof of the exceeding Populousness of the City at the time of the Infection, notwithstanding the great Numbers that were gone into the Country at the first Alarm, and that fled out into the Forests and Woods when they were farther terrifyed with the extraordinary Increase of it. For when we came to see the Crouds and Throngs of People, which appear’d on the Sabbath Days at the Churches, and especially in those parts of the Town where the Plague was abated, or where it was not yet come to its Height, it was amazing. But of this I shall speak again presently; I return in the mean time to the Article of infecting one another at first; before People came to right Notions of the Infection, and of infecting one another, People were only shye of those that were really sick, a Man with a Cap upon his Head, or with Cloths round his Neck, which was the Case of those that had Swellings there; such was indeed frightful: But when we saw a Gentleman dress’d, with his Band on and his Gloves in his Hand, his Hat upon his Head, and his Hair comb’d, of such we had not the least Apprehensions; and People conversed a great while freely, especially with their Neighbours and such as they knew. But when the Physicians assured us, that the Danger was as well from the Sound, that is the seemingly sound, as the Sick; and that those People, who thought themselves entirely free, were oftentimes the most fatal; and that it came to be generally understood, that People were sensible of it, and of the reason of it: Then I say they began to be jealous of every Body, and a vast Number of People lock’d themselves up, so as not to come abroad into any Company at all, nor suffer any, that had been abroad in promiscuous Company, to come into their Houses, or near them; at least not so near them, as to be within the Reach of their Breath, or of any Smell from them; and when they were oblig’d to converse at a Distance with Strangers, they would always have Preservatives in their Mouths, and about their Cloths to repell and keep off the Infection.

It must be acknowledg’d, that when People began to use these Cautions, they were less exposed to Danger, and the Infection did not break into such Houses so furiously as it did into others before, and thousands of Families were preserved, speaking with due Reserve to the Direction of Divine Providence, by that Means.

But it was impossible to beat any thing into the Heads of the Poor, they went on with the usual Impetuosity of their Tempers full of Outcries and Lamentations when taken, but madly careless of themselves, Fool-hardy and obstinate, while they were well: Where they could get Employment they push’d into any kind of Business, the most dangerous and the most liable to Infection; and if they were spoken to, their Answer would be, I must trust to God for that; if I am taken, then I am provided for, and there is an End of me, and the like: OR THUS, Why, What must I do? I can’t starve, I had as good have the Plague as perish for want. I have no Work, what could I do? I must do this or beg: Suppose it was burying the dead, or attending the Sick, or watching infected Houses, which were all terrible Hazards, but their Tale was generally the same. It is true Necessity was a very justifiable warrantable Plea, and nothing could be better; but their way of Talk was much the same, where the Necessities were not the same: This adventurous Conduct of the Poor was that which brought the Plague among them in a most furious manner, and this join’d to the Distress of their Circumstances, when taken, was the reason why they died so by Heaps; for I cannot say, I could observe one jot of better Husbandry among them, I mean the labouring Poor, while they were well and getting Money, than there was before, but as lavish, as extravagant, and as thoughtless for to-morrow as ever; so that when they came to be taken sick, they were immediately in the utmost Distress as well for want, as for Sickness, as well for lack of Food, as lack of Health.

This Misery of the Poor I had many Occasions to be an Eye-witness of, and sometimes also of the charitable Assistance that some pious People daily gave to such, sending them Relief and Supplies both of Food, Physick and other Help, as they found they wanted; and indeed it is a Debt of Justice due to the Temper of the People of that Day to take Notice here, that not only great Sums, very great Sums of Money were charitably sent to the Lord Mayor and Aldermen for the Assistance and Support of the poor distemper’d People; but abundance of private People daily distributed large Sums of Money for their Relief, and sent People about to enquire into the Condition of particular distressed and visited Families, and relieved them; nay some pious Ladies were so transported with Zeal in so good a Work, and so confident in the Protection of Providence in Discharge of the great Duty of Charity, that they went about in person distributing Alms to the Poor, and even visiting poor Families, tho’ sick and infected in their very Houses, appointing Nurses to attend those that wanted attending, and ordering Apothecaries and Surgeons, the first to supply them with Drugs or Plaisters, and such things as they wanted; and the last to lance and dress the Swellings and Tumours, where such were wanting; giving their Blessing to the Poor in substantial Relief to them, as well as hearty Prayers for them.

I will not undertake to say, as some do, that none of these charitable People were suffered to fall under the Calamity itself; but this I may say, that I never knew any one of them that miscarried, which I mention for the Encouragement of others in case of the like Distress; and doubtless, if they that give to the Poor, lend to the Lord, and he will repay them;* those that hazard their Lives to give to the Poor, and to comfort and assist the Poor in such a Misery as this, may hope to be protected in the Work.

Nor was this Charity so extraordinary eminent only in a few; but, (for I cannot lightly quit this Point) the Charity of the rich as well in the City and Suburbs as from the Country, was so great, that in a Word, a prodigious Number of People, who must otherwise inevitably have perished for want as well as Sickness, were supported and subsisted by it; and tho’ I could never, nor I believe any one else come to a full Knowledge of what was so contributed, yet I do believe, that as I heard one say, that was a critical Observer of that Part, there was not only many Thousand Pounds contributed, but many hundred thousand Pounds, to the Relief of the Poor of this distressed afflicted City; nay one Man affirm’d to me that he could reckon up above one hundred thousand Pounds a Week, which was distributed by the Church Wardens at the several Parish Vestries, by the Lord Mayor and the Aldermen in the several Wards and Precincts, and by the particular Direction of the Court and of the Justices respectively in the parts where they resided; over and above the private Charity distributed by pious Hands in the manner I speak of, and this continued for many Weeks together.

I confess this is a very great Sum; but if it be true, that there was distributed in the Parish of Cripplegate only 17800 Pounds* in one Week to the Relief of the Poor, as I heard reported, and which I really believe was true, the other may not be improbable.

It was doubtless to be reckon’d among the many signal good Providences which attended this great City, and of which there were many other worth recording; I say, this was a very remarkable one, that it pleased God thus to move the Hearts of the People in all parts of the Kingdom, so chearfully to contribute to the Relief and Support of the poor at London; the good Consequences of which were felt many ways, and particularly in preserving the Lives and recovering the Health of so many thousands, and keeping so many Thousands of Families from perishing and starving.

And now I am talking of the merciful Disposition of Providence in this time of Calamity, I cannot but mention again, tho’ I have spoken several times of it already on other Account, I mean that of the Progression of the Distemper; how it began at one end of the Town, and proceeded gradually and slowly from one Part to another, and like a dark Cloud that passes over our Heads, which as it thickens and overcasts the Air at one End, clears up at the other end: So while the Plague went on raging from West to East, as it went forwards East, it abated in the West, by which means those parts of the Town, which were not seiz’d, or who were left, and where it had spent its Fury, were (as it were) spar’d to help and assist the other; whereas had the Distemper spread it self over the whole City and Suburbs at once, raging in all Places alike, as it has done since in some Places abroad, the whole Body of the People must have been overwhelmed, and there would have died twenty thousand a Day, as they say there did at Naples,* nor would the People have been able to have help’d or assisted one another.

For it must be observ’d that where the Plague was in its full Force, there indeed the People were very miserable, and the Consternation was inexpressible. But a little before it reach’d even to that place, or presently after it was gone, they were quite another Sort of People, and I cannot but acknowledge, that there was too much of that common Temper of Mankind to be found among us all at that time; namely to forget the Deliverance, when the Danger is past: But I shall come to speak of that part again.

It must not be forgot here to take some Notice of the State of Trade, during the time of this common Calamity, and this with respect to Foreign Trade, as also to our Home-trade.

As to Foreign Trade, there needs little to be said; the trading Nations of Europe were all afraid of us, no Port of France, or Holland, or Spain, or Italy would admit our Ships or correspond with us; indeed we stood on ill Terms with the Dutch, and were in a furious War with them, but tho’ in a bad Condition to fight abroad, who had such dreadful Enemies to struggle with at Home.

Our Merchants accordingly were at a full Stop, their Ships could go no where, that is to say to no place abroad; their Manufactures and Merchandise, that is to say, of our Growth, would not be touch’d abroad; they were as much afraid of our Goods, as they were of our People; and indeed they had reason, for our woolen Manufactures are as retentive of Infection as human Bodies,* and if pack’d up by Persons infected would receive the Infection, and be as dangerous to touch, as a Man would be that was infected; and therefore when any English Vessel arriv’d in Foreign Countries, if they did take the Goods on Shore, they always caused the Bales to be opened and air’d in Places appointed for that Purpose: But from London they would not suffer them to come into Port, much less to unlade their Goods upon any Terms whatever; and this Strictness was especially us’d with them in Spain and Italy. In Turkey and the Islands of the Arches* indeed as they are call’d, as well those belonging to the Turks as to the Venetians, they were not so very rigid; in the first there was no Obstruction at all; and four Ships, which were then in the River loading for Italy, that is for Leghorn and Naples, being denyed Product, as they call it, went on to Turkey, and were freely admitted to unlade their Cargo without any Difficulty, only that when they arriv’d there, some of their Cargo was not fit for Sale in that Country, and other Parts of it being consign’d to Merchants at Leghorn, the Captains of the Ships had no Right nor any Orders to dispose of the Goods; so that great Inconveniences followed to the Merchants. But this was nothing but what the Necessity of Affairs requir’d, and the Merchants at Leghorn and at Naples having Notice given them, sent again from thence to take Care of the Effects, which were particularly consign’d to those Ports, and to bring back in other Ships such as were improper for the Markets at Smyrna and Scanderoon.*

The Inconveniences in Spain and Portugal were still greater; for they would, by no means, suffer our Ships, especially those from London, to come into any of their Ports, much less to unlade; there was a Report, that one of our Ships having by Stealth delivered her Cargo, among which was some Bales of English Cloth, Cotton, Kersyes, and such like Goods, the Spaniards caused all the Goods to be burnt, and punished the Men with Death who were concern’d in carrying them on Shore. This I believe was in Part true, tho’ I do not affirm it: But it is not at all unlikely, seeing the Danger was really very great, the Infection being so violent in London.

I heard likewise that the Plague was carryed into those Countries by some of our Ships, and particularly to the Port of Faro in the Kingdom of Algarve, belonging to the King of Portugal; and that several Persons died of it there, but it was not confirm’d.

On the other Hand, tho’ the Spaniards and Portuguese were so shie of us, it is most certain, that the Plague, as has been said, keeping at first much at that end of the Town next Westminster, the merchandising part of the Town, such as the City and the Water-side, was perfectly sound, till at least the Beginning of July; and the Ships in the River till the Beginning of August; for to the 1st of July, there had died but seven within the whole City,* and but 60 within the Liberties; but one in all the Parishes of Stepney, Aldgate, and White-Chappel; and but two in all the eight Parishes of Southwark. But it was the same thing abroad, for the bad News was gone over the whole World, that the City of London was infected with the Plague; and there was no inquiring there, how the Infection proceeded, or at which part of the Town it was begun, or was reach’d to.

Besides, after it began to spread, it increased so fast, and the Bills grew so high, all on a sudden, that it was to no purpose to lessen the Report of it, or endeavour to make the People abroad think it better than it was, the Account which the Weekly Bills gave in was sufficient; and that there died two thousand to three or four thousand a Week, was sufficient to alarm the whole trading part of the World, and the following time being so dreadful also in the very City it self, put the whole World, I say, upon their Guard against it.

You may be sure also, that the Report of these things lost nothing in the Carriage, the Plague was it self very terrible, and the Distress of the People very great, as you may observe by what I have said: But the Rumor was infinitely greater, and it must not be wonder’d, that our Friends abroad, as my Brother’s Correspondents in particular were told there, namely in Portugal and Italy where he chiefly traded, that in London there died twenty thousand in a Week; that the dead Bodies lay unburied by Heaps; that the living were not sufficient to bury the dead, or the Sound to look after the Sick; that all the Kingdom was infected likewise, so that it was an universal Malady, such as was never heard of in those parts of the World; and they could hardly believe us, when we gave them an Account how things really were, and how there was not above one Tenth part of the People dead; that there was 500000 left that lived all the time in the Town; that now the People began to walk the Streets again, and those, who were fled, to return, there was no Miss of the usual Throng of people in the Streets, except as every Family might miss their Relations and Neighbours, and the like; I say they could not believe these things; and if Enquiry were now to be made in Naples, or in other Cities on the Coast of Italy, they would tell you that there was a dreadful Infection in London so many Years ago; in which, as above, there died Twenty Thousand in a Week, &c. Just as we have had it reported in London, that there was a Plague in the City of Naples, in the Year 1656, in which there died 20000 People in a Day, of which I have had very good Satisfaction, that it was utterly false.

But these extravagant Reports were very prejudicial to our Trade as well as unjust and injurious in themselves; for it was a long Time after the Plague was quite over, before our Trade could recover it self in those parts of the World; and the Flemings and Dutch, but especially the last, made very great Advantages of it, having all the Market to themselves, and even buying our Manufactures in the several Parts of England where the Plague was not, and carrying them to Holland, and Flanders, and from thence transporting them to Spain, and to Italy, as if they had been of their own making.

But they were detected sometimes and punish’d, that is to say, their Goods confiscated, and Ships also; for if it was true, that our Manufactures, as well as our People, were infected,* and that it was dangerous to touch or to open, and receive the Smell of them; then those People ran the hazard by that clandestine Trade,* not only of carrying the Contagion into their own Country, but also of infecting the Nations to whom they traded with those Goods; which, considering how many Lives might be lost in Consequence of such an Action, must be a Trade that no Men of Conscience could suffer themselves to be concern’d in.

I do not take upon me to say, that any harm was done, I mean of that Kind, by those People: But I doubt I need not make any such Proviso in the Case of our own Country; for either by our People of London, or by the Commerce, which made their conversing with all Sorts of People in every County, and of every considerable Town, necessary, I say, by this means the Plague was first or last spread all over the Kingdom, as well in London as in all the Cities and great Towns, especially in the trading Manufacturing Towns, and Sea-Ports; so that first or last, all the considerable Places in England were visited more or less, and the Kingdom of Ireland in some Places, but not so universally; how it far’d with the People in Scotland, I had no opportunity to enquire.

It is to be observ’d, that while the Plague continued so violent in London, the out Ports, as they are call’d, enjoy’d a very great Trade, especially to the adjacent Countries, and to our own Plantations; for Example, the Towns of Colchester, Yarmouth, and Hull, on that side of England, exported to Holland and Hamburgh the Manufactures of the adjacent Counties for several Months after the Trade with London was as it were entirely shut up; likewise the Cities of Bristol and Exeter with the Port of Plymouth, had the like Advantage to Spain, to the Canaries, to Guinea, and to the West Indies; and particularly to Ireland; but as the Plague spread it self every way after it had been in London, to such a Degree as it was in August and September; so all, or most of those Cities and Towns were infected first or last, and then Trade was as it were under a general Embargo, or at a full stop,* as I shall observe farther, when I speak of our home Trade.

One thing however must be observed, that as to Ships coming in from Abroad, as many you may be sure did, some, who were out in all Parts of the World a considerable while before, and some who when they went out knew nothing of an Infection, or at least of one so terrible; these came up the River boldly, and delivered their Cargoes as they were oblig’d to do, except just in the two Months of August and September, when the Weight of the Infection lying, as I may say, all below Bridge, no Body durst appear in Business for a while: But as this continued but for a few Weeks, the Homeward bound Ships, especially such whose Cargoes were not liable to spoil, came to an Anchor for a Time, short of THE POOL1, or fresh Water part of the River, even as low as the River Medway, where several of them ran in, and others lay at the Nore, and in the Hope below Gravesend: So that by the latter end of October, there was a very great Fleet of Homeward bound Ships to come up, such as the like had not been known for many Years.

Two particular Trades were carried on by Water Carriage all the while of the Infection, and that with little or no Interruption, very much to the Advantage and Comfort of the poor distressed People of the City, and those were the coasting Trade for Corn, and the Newcastle Trade for Coals.*

The first of these was particularly carried on by small Vessels, from the Port of Hull, and other Places in the Humber, by which great Quantities of Corn were brought in from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire: The other part of this Corn-Trade was from Lynn in Norfolk, from Wells, and Burnham, and from Yarmouth, all in the same County; and the third Branch was from the River Medway, and from Milton, Feversham, Margate, and Sandwich, and all the other little Places and Ports round the Coast of Kent and Essex.

There was also a very good Trade from the Coast of Suffolk with Corn, Butter and Cheese; these Vessels kept a constant Course of Trade, and without Interruption came up to that Market known still by the Name of Bear-Key, where they supply’d the City plentifully with Corn, when Land Carriage began to fail, and when the People began to be sick of coming from many Places in the Country.

This also was much of it owing to the Prudence and Conduct of the Lord Mayor, who took such care to keep the Masters and Seamen from Danger, when they came up, causing their Corn to be bought off at any time they wanted a Market, (which however was very seldom) and causing the Corn-Factors immediately to unlade and deliver the Vessels loaden with Corn, that they had very little occasion to come out of their Ships or Vessels, the Money being always carried on Board to them, and put into a Pail of Vinegar before it was carried.

The second Trade was, that of Coals from Newcastle upon Tyne; without which the City would have been greatly distressed; for not in the Streets only, but in private Houses and Families, great Quantities of Coals were then burnt, even all the Summer long, and when the Weather was hottest, which was done by the Advice of the Physicians; some indeed oppos’d it, and insisted that to keep the Houses and Rooms hot, was a means to propagate the Distemper, which was a Fermentation and Heat already in the Blood, that it was known to spread, and increase in hot Weather, and abate in cold, and therefore they alledg’d that all contagious Distempers are the worse for Heat, because the Contagion was nourished, and gain’d Strength in hot Weather, and was as it were propagated in Heat.

Others said, they granted, that Heat in the Climate might propagate Infection, as sultry hot Weather fills the Air with Vermine, and nourishes innumerable Numbers, and Kinds of venomous Creatures, which breed in our Food, in the Plants, and even in our Bodies, by the very stench of which, Infection may be propagated; also, that heat in the Air, or heat of Weather, as we ordinarly call it, makes Bodies relax and faint, exhausts the Spirits, opens the Pores,* and makes us more apt to receive Infection, or any evil Influence, be it from noxious pestilential Vapors, or any other Thing in the Air: But that the heat of Fire, and especially of Coal Fires kept in our Houses, or near us, had a quite different Operation, the Heat being not of the same Kind, but quick and fierce, tending not to nourish but to consume, and dissipate all those noxious Fumes, which the other kind of Heat rather exhaled and stagnated than separated and burnt up; besides it was alledg’d, that the sulphurous and nitrous Particles, that are often found to be in the Coal, with that bituminous Substance which burns, are all assisting to clear and purge the Air, and render it wholsom and safe to breath[e] in, after the noctious Particles as above are dispersed and burnt up.

The latter Opinion prevail’d at that Time, and as I must confess I think with good Reason, and the Experience of the Citizens confirm’d it, many Houses which had constant Fires kept in the Rooms, having never been infected at all; and I must join my Experience to it, for I found the keeping good Fires kept our Rooms sweet and wholsom, and I do verily believe made our whole Family so, more than would otherwise have been.

But I return to the Coals as a Trade, it was with no little difficulty that this Trade was kept open, and particularly because as we were in an open War with the Dutch,* at that Time; the Dutch Capers at first took a great many of our Collier Ships, which made the rest cautious, and made them to stay to come in Fleets together: But after some time, the Capers were either afraid to take them, or their Masters, the States, were afraid they should, and forbad them, lest the Plague should be among them, which made them fare the better.

For the Security of those Northern Traders, the Coal Ships were order’d by my Lord Mayor, not to come up into the Pool above a certain Number at a Time, and order’d Lighters, and other Vessels, such as the Wood-mongers, that is the Wharf Keepers, or Coal-Sellers furnished, to go down, and take out the Coals as low as Deptford and Greenwich, and some farther down.

Others deliver’d great Quantities of Coals in particular Places, where the Ships cou’d come to the Shoar, as at Greenwich, Blackwal, and other Places, in vast Heaps, as if to be kept for Sale; but were then fetch’d away, after the Ships which brought them were gone; so that the Seamen had no Communication with the River-Men, nor so much as came near one another.

Yet all this Caution, could not effectually prevent the Distemper getting among the Colliery, that is to say, among the Ships, by which a great many Seamen died of it; and that which was still worse, was, that they carried it down to Ipswich, and Yarmouth, to Newcastle upon Tyne, and other Places on the Coast; where, especially at Newcastle and at Sunderland, it carried off a great Number of People.

The making so many Fires as above, did indeed consume an unusual Quantity of Coals; and that upon one or two stops of the Ships coming up, whether by contrary Weather, or by the Interruption of Enemies, I do not remember, but the Price of Coals was exceeding dear,* even as high as 4 1. a Chalder, but it soon abated when the Ships came in, and as afterwards they had a freer Passage, the Price was very reasonable all the rest of that Year.

The publick Fires* which were made on these Occasions, as I have calculated it, must necessarily have cost the City about 200 Chalder of Coals a Week, if they had continued, which was indeed a very great Quantity; but as it was, thought necessary, nothing was spar’d; however as some of the Physicians cry’d them down, they were not kept a-light above four or five Days; the Fires were order’d thus.

One at the Custom-house, one at Billingsgate, one at Queen-hith, and one at the Three Cranes, one in Black Friars, and one at the Gate of Bridewel, one at the Corner of Leadenhal Street, and Grace-church, one at the North, and one at the South Gate of the Royal Exchange, one at Guild Hall, and one at Blackwell-hall Gate, one at the Lord Mayor’s Door, in St.

1 comment