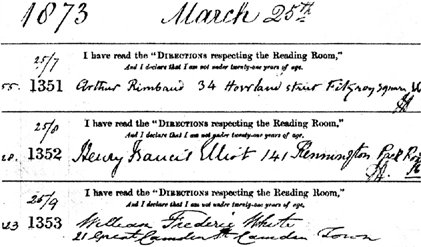

On the 25th of March, 1873, Rimbaud pushed through the padded leather doors that lead into the museum’s copper-domed Round Reading Room. And there, rung by a high circle of windows spilling daylight into the basin of tables—tables that would host Charles Dickens, Karl Marx, Virginia Woolf, and so many more—Rimbaud, the rebel, the blasphemer, the poet who would become famous for his “long, involved, and logical derangement of all the senses,” committed his most representative crime. Its inception remains indelibly marked on the library’s register for that day:

On line 1351, above the day’s eighth registrant (the pristinely forgotten Henry Elliot of Park Row), the day’s seventh applicant, eighteen-year-old Arthur Rimbaud, in a cramped hand, affirmed that he had read the “DIRECTIONS respecting the Reading Room”—

This was an old lie from the young man, one Rimbaud had been perfecting, in various forms, for years: when he was fifteen, sending poems and pleas from his home in the sticks to famous poets in Paris, claiming that he was seventeen (“Something in me … wants to break free”); or, when he was seventeen and writing them again, suggesting he was eighteen (“The same idiot is sending you more of his stuff.… Am I progressing?”). And yet, if Rimbaud’s early lies hooked him little more than minnows, the London version at last landed him a whale: a Reader’s Ticket to the great library, one that settled some of England’s choicest literary treasures into a boy’s scheming hands. This ticket gave Rimbaud the run of a collection that no less a littérateur than Vladimir Lenin (who told his own whopper when he registered there using the alias “Jacob Richter”) endorsed as having more Russian books than could be found in Russia. And with this rare abundance, not only in Russian books but in every language, what infamy did the eighteen-year-old Rimbaud then commit? What did this figure who subsequent generations of poets, the Pounds and Eliots and Cummingses (not to mention, later still, the Dylans and Morrisons and Reeds) looked to as the prototype of the bohemian poet, the rebel auteur, the sage and scourge—what, having lied his way into Alexandria, did Rimbaud then do?

In keeping with the conduct some anecdotes insist was his habit, it would not be unreasonable to wonder if Rimbaud began writing on table-tops, not with schoolboy pencils but, as some have reported he did in Paris cafés, with his own excrement. Or, in keeping with the behavior some contend was his custom, not unfathomable to suppose that he might have dropped his pants and, as some say he did into man’s glass of milk, ejaculated onto the pages of the Magna Carta. Or did this famously libidinous bard seduce unsuspecting scholars? Or did the bellicose poet cleave out the pages of books with the very same sword cane’s blade that perhaps pierced a photographer’s belly? Or, forgoing these trifles, these low sports, having come, after all, so far—from Paris, “the big shitty,” and before Paris, Charleville, the “moronic, provincial little town” from which he hailed—did Rimbaud decide, what the hell, to burn the place down to the ground?

Well, no. In fact, Rimbaud did nothing so supposedly Rimbaldean. He lied about his age, yes, but for one reason only, and not a particularly pornographic one: he lied so he could sit there, under the great dome, undisturbed, in good light, for weeks, and read.

The lives of writers are, not untypically, rather dull. A grotesque amount of time goes to waste, or seems to. Lock a man or woman in a room for ten years while he or she writes a novel or epic poem, and dinner-table talk tends to suffer, won’t overflow with thrilling tales. And so, in Rimbaud’s case, there is no question that his life supplies us with an uncommon quantity of entertaining hooks that might make the biographies of other writers seem, by comparison, dullsville. After all, Rimbaud did indeed write nearly all his poetry during his teens; and yes, truly, he was a serial runaway from fourteen on, hiking through France during wartime, alone; and absolutely he shoplifted; and sure he hightailed it repeatedly to Paris in the hope of being anointed by the poets he wished to have as peers; and you bet he was shot, in the wrist, by one of his lovers; and later, when he was done with poetry (for, of course, he famously said goodbye to poetry, at twenty-one, or, if not exactly goodbye, exited in the middle of the party and left the front door perplexingly wide open), he did sell grosses of guns to various African warlords. And, of course, there is his early, miserable death from cancer, or syphilis, or gangrene (for we cannot verify the cause), although we do know it followed complications that arose after the amputation of a leg, when he was just thirty-seven.

But this list of wicked plot points is, just that, a list, one I compiled in five minutes and which you read through in seconds. Rather than believing it tells us anything deeply revealing about Rimbaud’s life, and instead of seeing it as proof of regular, serial upheavals, one might instead acknowledge, after scanning them, that these events, really only a handful sprinkled over a life, were, however dark, ultimately incidental, minor marks on an otherwise pale sheet, punctuation that breaks the monotonous phrase printed there that better describes Rimbaud’s early life. That phrase? It says, in a repeating loop: a man, sitting, in various chairs, reading; a man, sitting, at various desks, writing.

And so, when we read Rimbaud’s letter to a friend, in May of 1873, composed shortly after he returned from his time spent reading in London, we get a truer sense of his days than the dirty thumbnail theater his bio might suggest. Sitting in a barn in his mother’s family farm in Roche—a very pastoral image that, one of well-fed livestock and clucking chickens—Rimbaud wrote to his boyhood friend Ernest Delahaye to gripe about his boredom: “What a pain in the ass, and what monstrous innocents these peasants are.” Rimbaud provided his friend with a sketch, his self-portrait-as-wandering-vagrant, complete with staff in hand:

He explained, too, what he was working on (“I’m doing some little prose pieces under the general title The Pagan Book or The Black Book”). He said he’d love to send these pieces to him but cried poverty (“I already have three: it costs too much!”). And then, in closing, made a request: that Delahaye ship him something tantalizing, something to sustain him in the wasteland of the French countryside, for “The French countryside is death.” And yet, Rimbaud asked neither for sex (in the form of illicit erotica); nor drugs (to feed his supposed program of seerdom); nor the nineteenth-century equivalent of rock and roll, whatever that might have been. On second thought, actually, Rimbaud did ask for the nineteenth-century equivalent of rock and roll, or what he might have viewed as such: Rimbaud asked his friend to send him more books.

It is a short list, but a list nonetheless and one that gives us more insight than we might imagine into those “little prose pieces” he was writing. In the May letter, he told Delahaye that “my fate rests with this book for which I still have a half-dozen horror-stories to make up. How does one make up atrocities here?” Well, it helps to have sources. Joyce could not have written Ulysses without Homer, nor Cummings his poetry without Sappho’s, nor Pound his without both those examples and Confucius’s teachings to boot—sources upon which to draw and distort, writers with whom to conspire. Thus Rimbaud told Delahaye, “I’ll soon send you stamps so you can buy and send me Goethe’s Faust … [and] see if there is any Shakespeare.”

Whether or not these were sent and, if sent, received is another of history’s shortfalls: we just don’t know. But reading Rimbaud’s prose pieces themselves, which is to say reading the book we know Rimbaud was writing that May—the book, A Season in Hell, that you now have in your hands—it is quite clear why he would have wanted what he demanded. That A Season in Hell was the book he was writing is known to us with any certainty is because, on the final page of the first edition, we find the following:

April-August: the season (and a half) when Rimbaud wishes us to understand that he wrote the seven thousand words that comprise the most important French poem of the nineteenth century. Not “most important” because it was the first or only such hybrid work; but because it was the first, in its content, to look both forward and backward through history and literature, using a knowledge of the two to write a poem very much about the present culture, a culture viewed, of course, through the agreeable myopia of a single reporter’s gaze. The poem unfolds, therefore, in that reportorial first person, but in a language that no one would mistake for having come from the newspaper. Which is not to say that the prose is purple, only deliberate, leached of sentimentality, hard-edged, distilled into soliloquies, nine of them (the three that had been written by May; the half-dozen he wrote thereafter).

1 comment