Daniel. Thoreau’s Morning Work: Memory and Perception in “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, ” the Journal, and “Walden. ” New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Radaker, Kevin. “ ‘A Separate Intention of the Eye’: Luminist Eternity in Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers,” Canadian Review of American Studies 18 (1987): 41-60.

Richardson, Robert D., Jr. Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Rossi, William. “Poetry and Progress: Thoreau, Lyell, and the Geological Principles of A Week,” American Literature 66 (1994): 275-300.

Rowe, John Carlos. Through the Custom House: Nineteenth-Century American Fiction and Modern Poetry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Sattelmeyer, Robert. Thoreau’s Reading: A Study in Intellectual History, With Bibliographical Catalogue. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Sayre, Robert F. Thoreau and the American Indians. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Schneider, Richard J. Henry David Thoreau. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1987.

Suchoff, David B. “ ‘A More Conscious Silence’: Friendship and Language in Thoreau’s Week,” ELH 49 (1982): 673-88.

Sundquist, Eric J. Home as Found: Authority and Genealogy in Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

Walls, Laura Dassow. Seeing New Worlds: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Natural Science. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

Yu, Ning. “Thoreau’s Critique of the American Pastoral in A Week,” Nineteenth-Century Literature 51 (1996): 304-27.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

The preparation of this Penguin Classics edition follows closely the procedures of Robert F. Sayre in his establishment of a text of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers for the Library of America volume, Henry David Thoreau (New York, 1985). Like that volume, this one depends primarily on the “New and Revised Edition” of A Week, published by Ticknor and Fields in 1868—six years after Thoreau’s death. Following the book’s initial publication in 1849 by James Munroe and Company, Thoreau made changes (including additions based on reading he is known to have done after 1849) on a copy, now lost, of A Week. It was this corrected copy that Thoreau’s sister Sophia and his friend Ellery Channing used in helping to prepare the 1868 edition. The 1868 edition also includes some changes that Thoreau had indicated on proofsheets for the first edition but which were not incorporated in that edition. Still other changes, which only Thoreau himself could have made, are drawn from pre-1849 drafts of A Week. Thus, the 1868 edition, while Thoreau was not alive to oversee its publication, clearly reflects his intentions for a revised and corrected version of A Week. Inevitably, some first-edition errors were carried over into the 1868 edition, and new typesetting errors occurred. For the methods used to resolve these types of problems, see “Note on the Texts” (pages 1053-54) in the Library of America edition.

Where‘er thou sail’st who sailed with me,

Though now thou climbest loftier mounts,

And fairer rivers dost ascend,

Be thou my Muse, my Brother—.

I am bound, I am bound, for a distant shore,

By a lonely isle, by a far Azore,

There it is, there it is, the treasure I seek,

On the barren sands of a desolate creek.

I sailed up a river with a pleasant wind,

New lands, new people, and new thoughts to find;

Many fair reaches and headlands appeared,

And many dangers were there to be feared;

But when I remember where I have been,

And the fair landscapes that I have seen,

THOU seemest the only permanent shore,

The cape never rounded, nor wandered o’er.

Fluminaque obliquis cinxit declivia ripis;

Quæ, diversa locis, partim sorbentur ab ipsa;

In mare perveniunt partim, campoque recepta

Liberioris aquæ, pro ripis litora pulsant.1

OVID, MET. I. 39.

He confined the rivers within their sloping banks,

Which in different places are part absorbed by the earth,

Part reach the sea, and being received within the plain

Of its freer waters, beat the shore for banks.

Concord River

“Beneath low hills, in the broad interval

Through which at will our Indian rivulet

Winds mindful still of sannup and of squaw,

Whose pipe and arrow oft the plough unburies,

Here, in pine houses, built of new-fallen trees,

Supplanters of the tribe, the farmers dwell.”1

EMERSON.

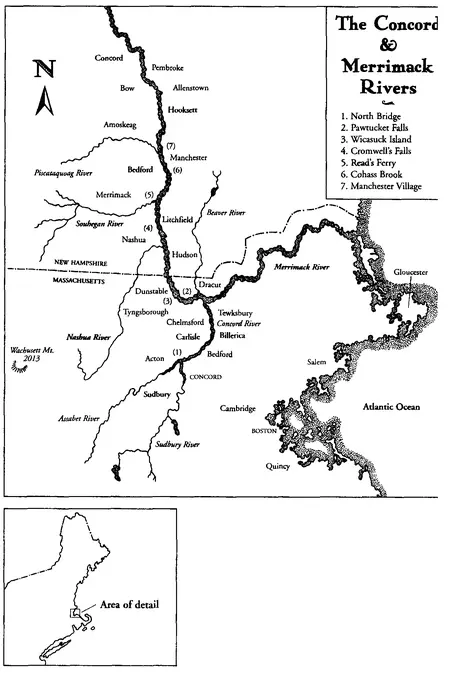

THE MUSKETAQUID, or Grass-ground River, though probably as old as the Nile or Euphrates, did not begin to have a place in civilized history, until the fame of its grassy meadows and its fish attracted settlers out of England in 1635, when it received the other but kindred name of CONCORD from the first plantation on its banks, which appears to have been commenced in a spirit of peace and harmony. It will be Grass-ground River as long as grass grows and water runs here; it will be Concord River only while men lead peaceable lives on its banks. To an extinct race it was grass-ground, where they hunted and fished, and it is still perennial grass-ground to Concord farmers, who own the Great Meadows, and get the hay from year to year. “One branch of it,” according to the historian of Concord,2 for I love to quote so good authority, “rises in the south part of Hopkinton, and another from a pond and a large cedar-swamp in Westborough,” and flowing between Hopkinton and Southborough, through Framingham, and between Sudbury and Wayland, where it is sometimes called Sudbury River, it enters Concord at the south part of the town, and after receiving the North or Assabeth River, which has its source a little farther to the north and west, goes out at the northeast angle, and flowing between Bedford and Carlisle, and through Billerica, empties into the Merrimack at Lowell. In Concord it is, in summer, from four to fifteen feet deep, and from one hundred to three hundred feet wide, but in the spring freshets, when it overflows its banks, it is in some places nearly a mile wide. Between Sudbury and Wayland the meadows acquire their greatest breadth, and when covered with water, they form a handsome chain of shallow vernal lakes, resorted to by numerous gulls and ducks. Just above Sherman’s Bridge, between these towns, is the largest expanse, and when the wind blows freshly in a raw March day, heaving up the surface into dark and sober billows or regular swells, skirted as it is in the distance with alder-swamps and smoke-like maples, it looks like a smaller Lake Huron, and is very pleasant and exciting for a landsman to row or sail over. The farm-houses along the Sudbury shore, which rises gently to a considerable height, command fine water prospects at this season. The shore is more flat on the Wayland side, and this town is the greatest loser by the flood.

1 comment