There is no need for a month yet."

"Nor even for a year," replied Niklausse, unfolding his pocket-handkerchief and calmly applying it to his nose.

There was another silence of nearly a quarter of an hour. Nothing disturbed this repeated pause in the conversation; not even the appearance of the house-dog Lento, who, not less phlegmatic than his master, came to pay his respects in the parlour. Noble dog!-- a model for his race. Had he been made of pasteboard, with wheels on his paws, he would not have made less noise during his stay.

Towards eight o'clock, after Lotchè had brought the antique lamp of polished glass, the burgomaster said to the counsellor,--

"We have no other urgent matter to consider?"

"No, Van Tricasse; none that I know of."

"Have I not been told, though," asked the burgomaster, "that the tower of the Oudenarde gate is likely to tumble down?"

"Ah!" replied the counsellor; "really, I should not be astonished if it fell on some passer-by any day."

"Oh! before such a misfortune happens I hope we shall have come to a decision on the subject of this tower."

"I hope so, Van Tricasse."

"There are more pressing matters to decide."

"No doubt; the question of the leather-market, for instance."

"What, is it still burning?"

"Still burning, and has been for the last three weeks."

"Have we not decided in council to let it burn?"

"Yes, Van Tricasse--on your motion."

"Was not that the surest and simplest way to deal with it?"

"Without doubt."

"Well, let us wait. Is that all?"

"All," replied the counsellor, scratching his head, as if to assure himself that he had not forgotten anything important.

"Ah!" exclaimed the burgomaster, "haven't you also heard something of an escape of water which threatens to inundate the low quarter of Saint Jacques?"

"I have. It is indeed unfortunate that this escape of water did not happen above the leather-market! It would naturally have checked the fire, and would thus have saved us a good deal of discussion."

"What can you expect, Niklausse? There is nothing so illogical as accidents. They are bound by no rules, and we cannot profit by one, as we might wish, to remedy another."

It took Van Tricasse's companion some time to digest this fine observation.

"Well, but," resumed the Counsellor Niklausse, after the lapse of some moments, "we have not spoken of our great affair!"

"What great affair? Have we, then, a great affair?" asked the burgomaster.

"No doubt. About lighting the town."

"O yes. If my memory serves me, you are referring to the lighting plan of Doctor Ox."

"Precisely."

"It is going on, Niklausse," replied the burgomaster. "They are already laying the pipes, and the works are entirely completed."

"Perhaps we have hurried a little in this matter," said the counsellor, shaking his head.

"Perhaps. But our excuse is, that Doctor Ox bears the whole expense of his experiment. It will not cost us a sou."

"That, true enough, is our excuse. Moreover, we must advance with the age. If the experiment succeeds, Quiquendone will be the first town in Flanders to be lighted with the oxy--What is the gas called?"

"Oxyhydric gas."

"Well, oxyhydric gas, then."

At this moment the door opened, and Lotchè came in to tell the burgomaster that his supper was ready.

Counsellor Niklausse rose to take leave of Van Tricasse, whose appetite had been stimulated by so many affairs discussed and decisions taken; and it was agreed that the council of notables should be convened after a reasonably long delay, to determine whether a decision should be provisionally arrived at with reference to the really urgent matter of the Oudenarde gate.

The two worthy administrators then directed their steps towards the street-door, the one conducting the other. The counsellor, having reached the last step, lighted a little lantern to guide him through the obscure streets of Quiquendone, which Doctor Ox had not yet lighted. It was a dark October night, and a light fog overshadowed the town.

Niklausse's preparations for departure consumed at least a quarter of an hour; for, after having lighted his lantern, he had to put on his big cow-skin socks and his sheep-skin gloves; then he put up the furred collar of his overcoat, turned the brim of his felt hat down over his eyes, grasped his heavy crow-beaked umbrella, and got ready to start.

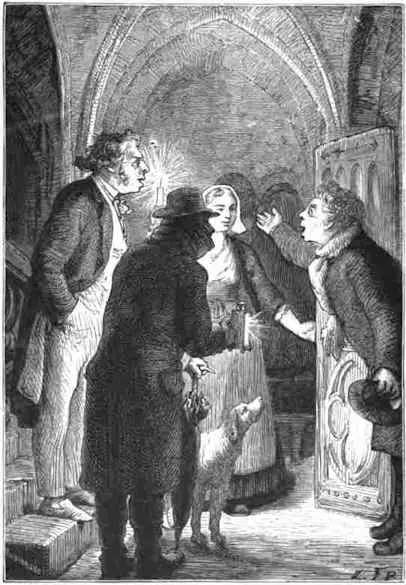

When Lotchè, however, who was lighting her master, was about to draw the bars of the door, an unexpected noise arose outside.

Yes! Strange as the thing seems, a noise--a real noise, such as the town had certainly not heard since the taking of the donjon by the Spaniards in 1513--terrible noise, awoke the long-dormant echoes of the venerable Van Tricasse mansion.

Some one knocked heavily upon this door, hitherto virgin to brutal touch! Redoubled knocks were given with some blunt implement, probably a knotty stick, wielded by a vigorous arm. With the strokes were mingled cries and calls. These words were distinctly heard:--

"Monsieur Van Tricasse! Monsieur the burgomaster! Open, open quickly!"

The burgomaster and the counsellor, absolutely astounded, looked at each other speechless.

This passed their comprehension. If the old culverin of the château, which had not been used since 1385, had been let off in the parlour, the dwellers in the Van Tricasse mansion would not have been more dumbfoundered.

Meanwhile, the blows and cries were redoubled. Lotchè, recovering her coolness, had plucked up courage to speak.

"Who is there?"

"It is I! I! I!"

"Who are you?"

"The Commissary Passauf!"

The Commissary Passauf! The very man whose office it had been contemplated to suppress for ten years. What had happened, then? Could the Burgundians have invaded Quiquendone, as they did in the fourteenth century? No event of less importance could have so moved Commissary Passauf, who in no degree yielded the palm to the burgomaster himself for calmness and phlegm.

On a sign from Van Tricasse--for the worthy man could not have articulated a syllable--the bar was pushed back and the door opened.

Commissary Passauf flung himself into the antechamber. One would have thought there was a hurricane.

"What's the matter, Monsieur the commissary?" asked Lotchè, a brave woman, who did not lose her head under the most trying circumstances.

"What's the matter!" replied Passauf, whose big round eyes expressed a genuine agitation. "The matter is that I have just come from Doctor Ox's, who has been holding a reception, and that there--"

I have just come from Doctor Ox's

"There?"

"There I have witnessed such an altercation as--Monsieur the burgomaster, they have been talking politics!"

"Politics!" repeated Van Tricasse, running his fingers through his wig.

"Politics!" resumed Commissary Passauf, "which has not been done for perhaps a hundred years at Quiquendone. Then the discussion got warm, and the advocate, André Schut, and the doctor, Dominique Custos, became so violent that it may be they will call each other out."

"Call each other out!" cried the counsellor. "A duel! A duel at Quiquendone! And what did Advocate Schut and Doctor Gustos say?"

"Just this: 'Monsieur advocate,' said the doctor to his adversary, 'you go too far, it seems to me, and you do not take sufficient care to control your words!'"

The Burgomaster Van Tricasse clasped his hands--the counsellor turned pale and let his lantern fall--the commissary shook his head. That a phrase so evidently irritating should be pronounced by two of the principal men in the country!

"This Doctor Custos," muttered Van Tricasse, "is decidedly a dangerous man--a hare-brained fellow! Come, gentlemen!"

On this, Counsellor Niklausse and the commissary accompanied the burgomaster into the parlour.

CHAPTER IV.

IN WHICH DOCTOR OX REVEALS HIMSELF AS A PHYSIOLOGIST OF THE FIRST RANK, AND AS AN AUDACIOUS EXPERIMENTALIST.

Who, then, was this personage, known by the singular name of Doctor Ox?

An original character for certain, but at the same time a bold savant, a physiologist, whose works were known and highly estimated throughout learned Europe, a happy rival of the Davys, the Daltons, the Bostocks, the Menzies, the Godwins, the Vierordts--of all those noble minds who have placed physiology among the highest of modern sciences.

Doctor Ox was a man of medium size and height, aged--: but we cannot state his age, any more than his nationality. Besides, it matters little; let it suffice that he was a strange personage, impetuous and hot-blooded, a regular oddity out of one of Hoffmann's volumes, and one who contrasted amusingly enough with the good people of Quiquendone. He had an imperturbable confidence both in himself and in his doctrines. Always smiling, walking with head erect and shoulders thrown back in a free and unconstrained manner, with a steady gaze, large open nostrils, a vast mouth which inhaled the air in liberal draughts, his appearance was far from unpleasing. He was full of animation, well proportioned in all parts of his bodily mechanism, with quicksilver in his veins, and a most elastic step.

1 comment