The main pipes and branches gradually crept beneath the pavements. But the burners were still wanting; for, as it required delicate skill to make them, it was necessary that they should be fabricated abroad. Doctor Ox was here, there, and everywhere; neither he nor Ygène, his assistant, lost a moment, but they urged on the workmen, completed the delicate mechanism of the gasometer, fed day and night the immense piles which decomposed the water under the influence of a powerful electric current. Yes, the doctor was already making his gas, though the pipe-laying was not yet done; a fact which, between ourselves, might have seemed a little singular. But before long,--at least there was reason to hope so,--before long Doctor Ox would inaugurate the splendours of his invention in the theatre of the town.

For Quiquendone possessed a theatre--a really fine edifice, in truth--the interior and exterior arrangement of which combined every style of architecture. It was at once Byzantine, Roman, Gothic, Renaissance, with semicircular doors, Pointed windows, Flamboyant rose-windows, fantastic bell-turrets,--in a word, a specimen of all sorts, half a Parthenon, half a Parisian Grand Café. Nor was this surprising, the theatre having been commenced under the burgomaster Ludwig Van Tricasse, in 1175, and only finished in 1837, under the burgomaster Natalis Van Tricasse. It had required seven hundred years to build it, and it had, been successively adapted to the architectural style in vogue in each period. But for all that it was an imposing structure; the Roman pillars and Byzantine arches of which would appear to advantage lit up by the oxyhydric gas.

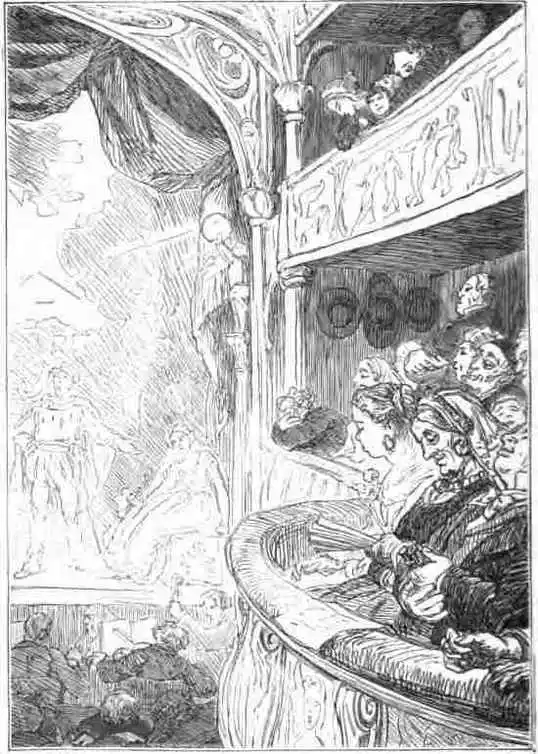

Pretty well everything was acted at the theatre of Quiquendone; but the opera and the opera comique were especially patronized. It must, however, be added that the composers would never have recognized their own works, so entirely changed were the "movements" of the music.

In short, as nothing was done in a hurry at Quiquendone, the dramatic pieces had to be performed in harmony with the peculiar temperament of the Quiquendonians. Though the doors of the theatre were regularly thrown open at four o'clock and closed again at ten, it had never been known that more than two acts were played during the six intervening hours. "Robert le Diable," "Les Huguenots," or "Guillaume Tell" usually took up three evenings, so slow was the execution of these masterpieces. The vivaces, at the theatre of Quiquendone, lagged like real adagios. The allegros were "long-drawn out" indeed. The demisemiquavers were scarcely equal to the ordinary semibreves of other countries. The most rapid runs, performed according to Quiquendonian taste, had the solemn march of a chant. The gayest shakes were languishing and measured, that they might not shock the ears of the dilettanti. To give an example, the rapid air sung by Figaro, on his entrance in the first act of "Le Barbiér de Séville," lasted fifty-eight minutes--when the actor was particularly enthusiastic.

Artists from abroad, as might be supposed, were forced to conform themselves to Quiquendonian fashions; but as they were well paid, they did not complain, and willingly obeyed the leader's baton, which never beat more than eight measures to the minute in the allegros.

But what applause greeted these artists, who enchanted without ever wearying the audiences of Quiquendone! All hands clapped one after another at tolerably long intervals, which the papers characterized as "frantic applause;" and sometimes nothing but the lavish prodigality with which mortar and stone had been used in the twelfth century saved the roof of the hall from falling in.

Besides, the theatre had only one performance a week, that these enthusiastic Flemish folk might not be too much excited; and this enabled the actors to study their parts more thoroughly, and the spectators to digest more at leisure the beauties of the masterpieces brought out.

Such had long been the drama at Quiquendone. Foreign artists were in the habit of making engagements with the director of the town, when they wanted to rest after their exertions in other scenes; and it seemed as if nothing could ever change these inveterate customs, when, a fortnight after the Schut-Custos affair, an unlooked-for incident occurred to throw the population into fresh agitation.

It was on a Saturday, an opera day. It was not yet intended, as may well be supposed, to inaugurate the new illumination. No; the pipes had reached the hall, but, for reasons indicated above, the burners had not yet been placed, and the wax-candles still shed their soft light upon the numerous spectators who filled the theatre. The doors had been opened to the public at one o'clock, and by three the hall was half full. A queue had at one time been formed, which extended as far as the end of the Place Saint Ernuph, in front of the shop of Josse Lietrinck the apothecary. This eagerness was significant of an unusually attractive performance.

"Are you going to the theatre this evening?" inquired the counsellor the same morning of the burgomaster.

"I shall not fail to do so," returned Van Tricasse, "and I shall take Madame Van Tricasse, as well as our daughter Suzel and our dear Tatanémance, who all dote on good music."

"Mademoiselle Suzel is going then?"

"Certainly, Niklausse."

"Then my son Frantz will be one of the first to arrive," said Niklausse.

"A spirited boy, Niklausse," replied the burgomaster sententiously; "but hot-headed! He will require watching!"

"He loves, Van Tricasse,--he loves your charming Suzel."

"Well, Niklausse, he shall marry her. Now that we have agreed on this marriage, what more can he desire?"

"He desires nothing, Van Tricasse, the dear boy! But, in short-- we'll say no more about it--he will not be the last to get his ticket at the box-office."

"Ah, vivacious and ardent youth!" replied the burgomaster, recalling his own past. "We have also been thus, my worthy counsellor! We have loved--we too! We have danced attendance in our day! Till to-night, then, till to-night! By-the-bye, do you know this Fiovaranti is a great artist? And what a welcome he has received among us! It will be long before he will forget the applause of Quiquendone!"

The tenor Fiovaranti was, indeed, going to sing; Fiovaranti, who, by his talents as a virtuoso, his perfect method, his melodious voice, provoked a real enthusiasm among the lovers of music in the town.

For three weeks Fiovaranti had been achieving a brilliant success in "Les Huguenots." The first act, interpreted according to the taste of the Quiquendonians, had occupied an entire evening of the first week of the month.--Another evening in the second week, prolonged by infinite andantes, had elicited for the celebrated singer a real ovation. His success had been still more marked in the third act of Meyerbeer's masterpiece. But now Fiovaranti was to appear in the fourth act, which was to be performed on this evening before an impatient public. Ah, the duet between Raoul and Valentine, that pathetic love-song for two voices, that strain so full of crescendos, stringendos, and piu crescendos--all this, sung slowly, compendiously, interminably! Ah, how delightful!

Fiovaranti had been achieving a brilliant success in "Les Huguenots."

At four o'clock the hall was full. The boxes, the orchestra, the pit, were overflowing.

1 comment