It is true that Alexander's soldiers, about to leave their homes to go to another quarter of the globe, and into scenes of danger and death from which it was very improbable that many of them would ever return, had no other celestial protection to look up to than the spirits of ancient heroes, who, they imagined, had, somehow or other, found their final home in a sort of heaven among the summits of the mountains, where they reigned, in some sense, over human affairs; but this, small as it seems to us, was a great deal to them. They felt, when sacrificing to these gods, that they were invoking their presence and sympathy. These deities having been engaged in the same enterprises themselves, and animated with the same hopes and fears, the soldiers imagined that the semi-human divinities invoked by them would take an interest in their dangers, and rejoice is their success.

The nine Muses.

The Muses, in honor of whom, as well as Jupiter, this great Macedonian festival was held, were nine singing and dancing maidens, beautiful in countenance and form, and enchantingly graceful in all their movements. They came, the ancients imagined, from Thrace, in the north, and went first to Jupiter upon Mount Olympus, who made them goddesses. Afterward they went southward, and spread over Greece, making their residence, at last, in a palace upon Mount Parnassus, which will be found upon the map just north of the Gulf of Corinth and west of Bœotia. They were worshiped all over Greece and Italy as the goddesses of music and dancing. In later times particular sciences and arts were assigned to them respectively, as history, astronomy, tragedy, &c., though there was no distinction of this kind in early days.

Festivities in honor of Jupiter.

Spectacles and shows.

The festivities in honor of Jupiter and the Muses were continued in Macedon nine days, a number corresponding with that of the dancing goddesses. Alexander made very magnificent preparations for the celebration on this occasion. He had a tent made, under which, it is said, a hundred tables could be spread; and here he entertained, day after day, an enormous company of princes, potentates, and generals. He offered sacrifices to such of the gods as he supposed it would please the soldiers to imagine that they had propitiated. Connected with these sacrifices and feastings, there were athletic and military spectacles and shows—races and wrestlings—and mock contests, with blunted spears. All these things encouraged and quickened the ardor and animation of the soldiers. It aroused their ambition to distinguish themselves by their exploits, and gave them an increased and stimulated desire for honor and fame. Thus inspirited by new desires for human praise, and trusting in the sympathy and protection of powers which were all that they conceived of as divine, the army prepared to set forth from their native land, bidding it a long, and, as it proved to most of them, a final farewell.

Alexander's route.

Alexander begins his march.

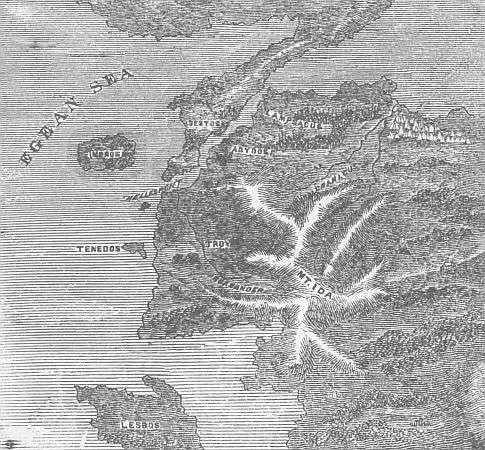

By following the course of Alexander's expedition upon the map at the commencement of chapter iii., it will be seen that his route lay first along the northern coasts of the Ægean Sea. He was to pass from Europe into Asia by crossing the Hellespont between Sestos and Abydos. He sent a fleet of a hundred and fifty galleys, of three banks of oars each, over the Ægean Sea, to land at Sestos, and be ready to transport his army across the straits. The army, in the mean time, marched by land. They had to cross the rivers which flow into the Ægean Sea on the northern side; but as these rivers were in Macedon, and no opposition was encountered upon the banks of them, there was no serious difficulty in effecting the passage. When they reached Sestos, they found the fleet ready there, awaiting their arrival.

Romantic adventure.

It is very strikingly characteristic of the mingling of poetic sentiment and enthusiasm with calm and calculating business efficiency, which shone conspicuously so often in Alexander's career, that when he arrived at Sestos, and found that the ships were there, and the army safe, and that there was no enemy to oppose his landing on the Asiatic shore, he left Parmenio to conduct the transportation of the troops across the water, while he himself went away in a single galley on an excursion of sentiment and romantic adventure. A little south of the place where his army was to cross, there lay, on the Asiatic shore, an extended plain, on which were the ruins of Troy. Now Troy was the city which was the scene of Homer's poems—those poems which had excited so much interest in the mind of Alexander in his early years; and he determined, instead of crossing the Hellespont with the main body of his army, to proceed southward in a single galley, and land, himself, on the Asiatic shore, on the very spot which the romantic imagination of his youth had dwelt upon so often and so long.

The Plain of Troy.

The Plain of Troy.

[Enlarge]

The plain of Troy.

Tenedos.

Mount Ida.

The Scamander.

Troy was situated upon a plain. Homer describes an island off the coast, named Tenedos, and a mountain near called Mount Ida. There was also a river called the Scamander. The island, the mountain, and the river remain, preserving their original names to the present day, except that the river is now called the Mender, but, although various vestiges of ancient ruins are found scattered about the plain, no spot can be identified as the site of the city. Some scholars have maintained that there probably never was such a city; that Homer invented the whole, there being nothing real in all that he describes except the river, the mountain, and the island. His story is, however, that there was a great and powerful city there, with a kingdom attached to it, and that this city was besieged by the Greeks for ten years, at the end of which time it was taken and destroyed.

The Trojan war.

Dream of Priam's wife.

Exposure of Paris.

The story of the origin of this war is substantially this. Priam was king of Troy. His wife, a short time before her son was born, dreamed that at his birth the child turned into a torch and set the palace on fire. She told this dream to the soothsayers, and asked them what it meant. They said it must mean that her son would be the means of bringing some terrible calamities and disasters upon the family.

1 comment