Alexander overtook them on their march, not far from the place of their landing. To the northward of this place, on the left of the line of march which Alexander was taking, was the city of Lampsacus.

Alexander spares Lampsacus.

Now a large portion of Asia Minor, although for the most part under the dominion of Persia, had been in a great measure settled by Greeks, and, in previous wars between the two nations, the various cities had been in possession, sometimes of one power and sometimes of the other. In these contests the city of Lampsacus had incurred the high displeasure of the Greeks by rebelling, as they said, on one occasion, against them. Alexander determined to destroy it as he passed. The inhabitants were aware of this intention, and sent an embassador to Alexander to implore his mercy. When the embassador approached, Alexander, knowing his errand, uttered a declaration in which he bound himself by a solemn oath not to grant the request he was about to make. "I have come," said the embassador, "to implore you to destroy Lampsacus." Alexander, pleased with the readiness of the embassador in giving his language such a sudden turn, and perhaps influenced by his oath, spared the city.

Arrival at the Granicus.

He was now fairly in Asia. The Persian forces were gathering to attack him, but so unexpected and sudden had been his invasion that they were not prepared to meet him at his arrival, and he advanced without opposition till he reached the banks of the little river Granicus.

Chapter V.

Campaign in Asia Minor.

B.C. 334-333

Alexander hemmed in by Mount Ida and the Granicus.

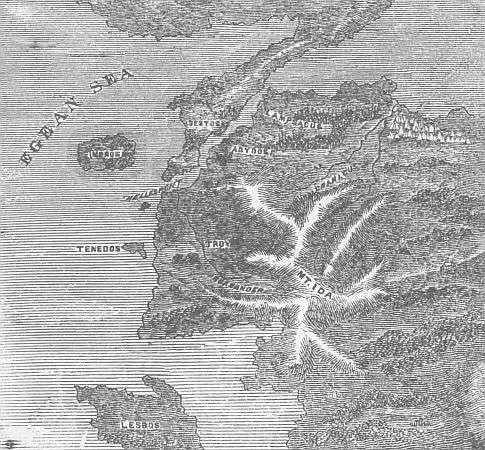

Although Alexander had landed safely on the Asiatic shore, the way was not yet fairly open for him to advance into the interior of the country. He was upon a sort of plain, which was separated from the territory beyond by natural barriers. On the south was the range of lofty land called Mount Ida. From the northeastern slopes of this mountain there descended a stream which flowed north into the sea, thus hemming Alexander's army in. He must either scale the mountain or cross the river before he could penetrate into the interior.

The Granicus.

He thought it would be easiest to cross the river. It is very difficult to get a large body of horsemen and of heavy-armed soldiers, with all their attendants and baggage, over high elevations of land. This was the reason why the army turned to the northward after landing upon the Asiatic shore. Alexander thought the Granicus less of an obstacle than Mount Ida. It was not a large stream, and was easily fordable.

The Granicus.

The Granicus.

[Enlarge]

Prodromi.

It was the custom in those days, as it is now when armies are marching, to send forward small bodies of men in every direction to explore the roads, remove obstacles, and discover sources of danger. These men are called, in modern times, scouts; in Alexander's day, and in the Greek language, they were called prodromi, which means forerunners. It is the duty of these pioneers to send messengers back continually to the main body of the army, informing the officers of every thing important which comes under their observation.

Alexander stopped at the Granicus.

Council called.

In this case, when the army was gradually drawing near to the river, the prodromi came in with the news that they had been to the river, and found the whole opposite shore, at the place of crossing, lined with Persian troops, collected there to dispute the passage. The army continued their advance, while Alexander called the leading generals around him, to consider what was to be done.

Parmenio recommended that they should not attempt to pass the river immediately. The Persian army consisted chiefly of cavalry. Now cavalry, though very terrible as an enemy on the field of battle by day, are peculiarly exposed and defenseless in an encampment by night. The horses are scattered, feeding or at rest. The arms of the men are light, and they are not accustomed to fighting on foot; and on a sudden incursion of an enemy at midnight into their camp, their horses and their horsemanship are alike useless, and they fall an easy prey to resolute invaders. Parmenio thought, therefore, that the Persians would not dare to remain and encamp many days in the vicinity of Alexander's army, and that, accordingly, if they waited a little, the enemy would retreat, and Alexander could then cross the river without incurring the danger of a battle.

Alexander resolves to advance.

His motives.

But Alexander was unwilling to adopt any such policy. He felt confident that his army was courageous and strong enough to march on, directly through the river, ascend the bank upon the other side, and force their way through all the opposition which the Persians could make. He knew, too, that if this were done it would create a strong sensation throughout the whole country, impressing every one with a sense of the energy and power of the army which he was conducting, and would thus tend to intimidate the enemy, and facilitate all future operations. But this was not all; he had a more powerful motive still for wishing to march right on, across the river, and force his way through the vast bodies of cavalry on the opposite shore, and this was the pleasure of performing the exploit.

The Macedonian phalanx.

Its organization.

Accordingly, as the army advanced to the banks, they maneuvered to form in order of battle, and prepared to continue their march as if there were no obstacle to oppose them. The general order of battle of the Macedonian army was this. There was a certain body of troops, armed and organized in a peculiar manner, called the Phalanx.

1 comment