I suppose I ought to eat or drink something or other, but the great question is "What?""

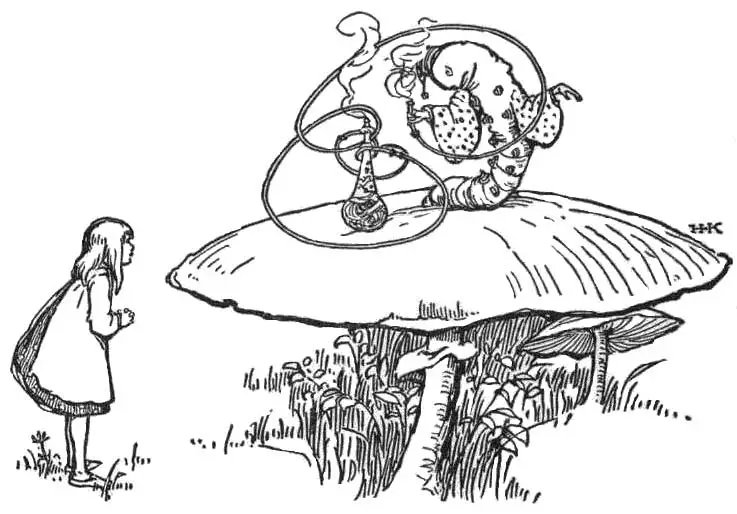

Alice looked all around her at the flowers and the blades of grass, but she could not see anything that looked like the right thing to eat or drink under the circumstances. There was a large mushroom growing near her, about the same height as herself. She stretched herself up on tiptoe and peeped over the edge and her eyes immediately met those of a large blue caterpillar, that was sitting on the top, with its arms folded, quietly smoking a long hookah and taking not the smallest notice of her or of anything else.

V—ADVICE FROM A CATERPILLAR

At last the Caterpillar took the hookah out of its mouth and addressed Alice in a languid, sleepy voice.

"Who are you?" said the Caterpillar.

Alice replied, rather shyly, "I—I hardly know, sir, just at present—at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have changed several times since then."

"What do you mean by that?" said the Caterpillar, sternly. "Explain yourself!"

"I can't explain myself, I'm afraid, sir," said Alice, "because I'm not myself, you see—being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing." She drew herself up and said very gravely, "I think you ought to tell me who you are, first."

"Why?" said the Caterpillar.

As Alice could not think of any good reason and the Caterpillar seemed to be in a very unpleasant state of mind, she turned away.

"Come back!" the Caterpillar called after her. "I've something important to say!" Alice turned and came back again.

"Keep your temper," said the Caterpillar.

"Is that all?" said Alice, swallowing down her anger as well as she could.

"No," said the Caterpillar.

It unfolded its arms, took the hookah out of its mouth again, and said, "So you think you're changed, do you?"

"I'm afraid, I am, sir," said Alice. "I can't remember things as I used—and I don't keep the same size for ten minutes together!"

"What size do you want to be?" asked the Caterpillar.

"Oh, I'm not particular as to size," Alice hastily replied, "only one doesn't like changing so often, you know. I should like to be a little larger, sir, if you wouldn't mind," said Alice. "Three inches is such a wretched height to be."

"It is a very good height indeed!" said the Caterpillar angrily, rearing itself upright as it spoke (it was exactly three inches high).

In a minute or two, the Caterpillar got down off the mushroom and crawled away into the grass, merely remarking, as it went, "One side will make you grow taller, and the other side will make you grow shorter."

"One side of what? The other side of what?" thought Alice to herself.

"Of the mushroom," said the Caterpillar, just as if she had asked it aloud; and in another moment, it was out of sight.

Alice remained looking thoughtfully at the mushroom for a minute, trying to make out which were the two sides of it. At last she stretched her arms 'round it as far as they would go, and broke off a bit of the edge with each hand.

"And now which is which?" she said to herself, and nibbled a little of the right–hand bit to try the effect. The next moment she felt a violent blow underneath her chin—it had struck her foot!

She was a good deal frightened by this very sudden change, as she was shrinking rapidly; so she set to work at once to eat some of the other bit. Her chin was pressed so closely against her foot that there was hardly room to open her mouth; but she did it at last and managed to swallow a morsel of the left–hand bit….

"Come, my head's free at last!" said Alice; but all she could see, when she looked down, was an immense length of neck, which seemed to rise like a stalk out of a sea of green leaves that lay far below her.

"Where have my shoulders got to? And oh, my poor hands, how is it I can't see you?" She was delighted to find that her neck would bend about easily in any direction, like a serpent. She had just succeeded in curving it down into a graceful zigzag and was going to dive in among the leaves, when a sharp hiss made her draw back in a hurry—a large pigeon had flown into her face and was beating her violently with its wings.

"Serpent!" cried the Pigeon.

"I'm not a serpent!" said Alice indignantly. "Let me alone!"

"I've tried the roots of trees, and I've tried banks, and I've tried hedges," the Pigeon went on, "but those serpents! There's no pleasing them!"

Alice was more and more puzzled.

"As if it wasn't trouble enough hatching the eggs," said the Pigeon, "but I must be on the look–out for serpents, night and day! And just as I'd taken the highest tree in the wood," continued the Pigeon, raising its voice to a shriek, "and just as I was thinking I should be free of them at last, they must needs come wriggling down from the sky! Ugh, Serpent!"

"But I'm not a serpent, I tell you!" said Alice. "I'm a—I'm a—I'm a little girl," she added rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through that day.

"You're looking for eggs, I know that well enough," said the Pigeon; "and what does it matter to me whether you're a little girl or a serpent?"

"It matters a good deal to me," said Alice hastily; "but I'm not looking for eggs, as it happens, and if I was, I shouldn't want yours—I don't like them raw."

"Well, be off, then!" said the Pigeon in a sulky tone, as it settled down again into its nest. Alice crouched down among the trees as well as she could, for her neck kept getting entangled among the branches, and every now and then she had to stop and untwist it. After awhile she remembered that she still held the pieces of mushroom in her hands, and she set to work very carefully, nibbling first at one and then at the other, and growing sometimes taller and sometimes shorter, until she had succeeded in bringing herself down to her usual height.

It was so long since she had been anything near the right size that it felt quite strange at first. "The next thing is to get into that beautiful garden—how is that to be done, I wonder?" As she said this, she came suddenly upon an open place, with a little house in it about four feet high. "Whoever lives there," thought Alice, "it'll never do to come upon them this size; why, I should frighten them out of their wits!" She did not venture to go near the house till she had brought herself down to nine inches high.

VI—PIG AND PEPPER

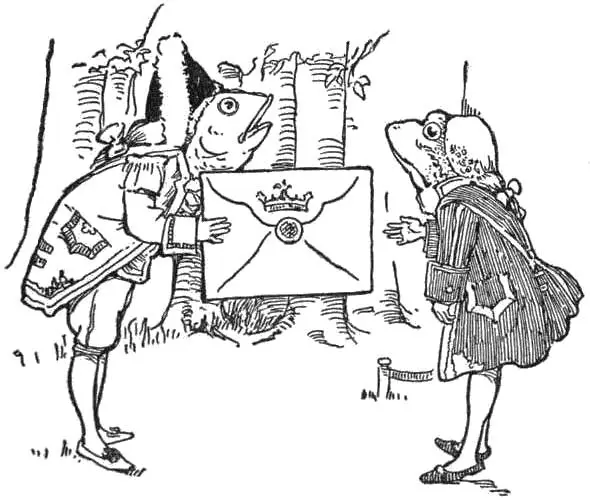

For a minute or two she stood looking at the house, when suddenly a footman in livery came running out of the wood (judging by his face only, she would have called him a fish)—and rapped loudly at the door with his knuckles. It was opened by another footman in livery, with a round face and large eyes like a frog.

The Fish–Footman began by producing from under his arm a great letter, and this he handed over to the other, saying, in a solemn tone, "For the Duchess. An invitation from the Queen to play croquet." The Frog–Footman repeated, in the same solemn tone, "From the Queen. An invitation for the Duchess to play croquet." Then they both bowed low and their curls got entangled together.

When Alice next peeped out, the Fish–Footman was gone, and the other was sitting on the ground near the door, staring stupidly up into the sky. Alice went timidly up to the door and knocked.

"There's no sort of use in knocking," said the Footman, "and that for two reasons. First, because I'm on the same side of the door as you are; secondly, because they're making such a noise inside, no one could possibly hear you." And certainly there was a most extraordinary noise going on within—a constant howling and sneezing, and every now and then a great crash, as if a dish or kettle had been broken to pieces.

"How am I to get in?" asked Alice.

"Are you to get in at all?" said the Footman. "That's the first question, you know."

Alice opened the door and went in. The door led right into a large kitchen, which was full of smoke from one end to the other; the Duchess was sitting on a three–legged stool in the middle, nursing a baby; the cook was leaning over the fire, stirring a large caldron which seemed to be full of soup.

"There's certainly too much pepper in that soup!" Alice said to herself, as well as she could for sneezing. Even the Duchess sneezed occasionally; and as for the baby, it was sneezing and howling alternately without a moment's pause. The only two creatures in the kitchen that did not sneeze were the cook and a large cat, which was grinning from ear to ear.

"Please would you tell me," said Alice, a little timidly, "why your cat grins like that?"

"It's a Cheshire–Cat," said the Duchess, "and that's why."

"I didn't know that Cheshire–Cats always grinned; in fact, I didn't know that cats could grin," said Alice.

"You don't know much," said the Duchess, "and that's a fact."

Just then the cook took the caldron of soup off the fire, and at once set to work throwing everything within her reach at the Duchess and the baby—the fire–irons came first; then followed a shower of saucepans, plates and dishes. The Duchess took no notice of them, even when they hit her, and the baby was howling so much already that it was quite impossible to say whether the blows hurt it or not.

"Oh, please mind what you're doing!" cried Alice, jumping up and down in an agony of terror.

"Here! You may nurse it a bit, if you like!" the Duchess said to Alice, flinging the baby at her as she spoke. "I must go and get ready to play croquet with the Queen," and she hurried out of the room.

Alice caught the baby with some difficulty, as it was a queer–shaped little creature and held out its arms and legs in all directions. "If I don't take this child away with me," thought Alice, "they're sure to kill it in a day or two.

1 comment