Amok and Other Stories

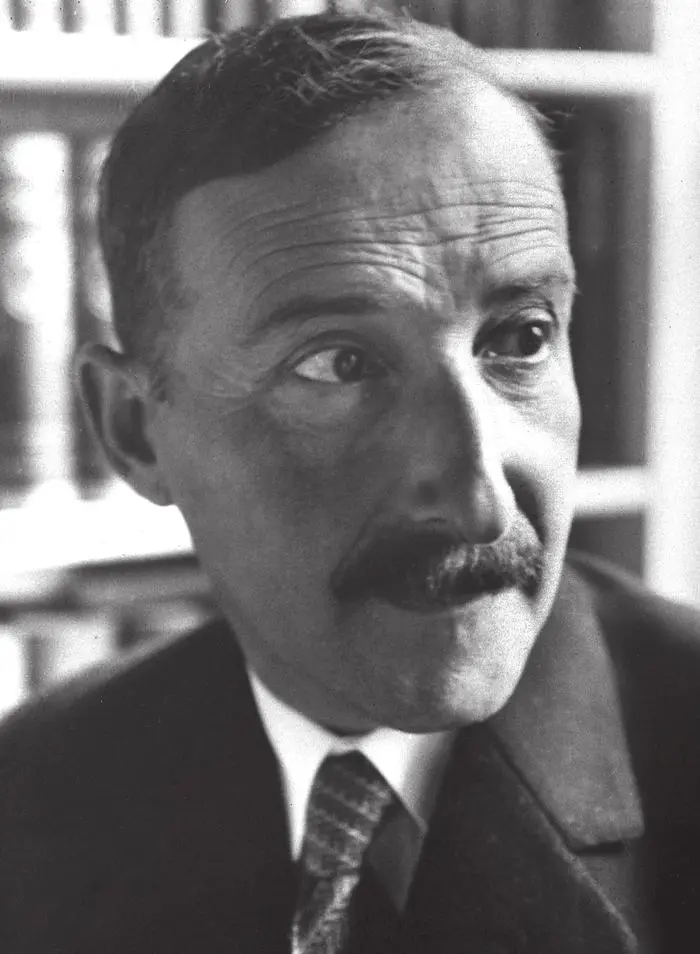

STEFAN ZWEIG

AMOK

AND OTHER STORIES

Translated from the German by

Anthea Bell

PUSHKIN PRESS

LONDON

CONTENTS

Title Page

Amok

The Star above the Forest

Leporella

Incident on Lake Geneva

Translator’s Afterword

Copyright

IN MARCH 1912 A STRANGE ACCIDENT occurred in Naples harbour during the unloading of a large ocean-going liner which was reported at length by the newspapers, although in extremely fanciful terms. Although I was a passenger on the Oceania, I did not myself witness this strange incident—nor did any of the others—since it happened while coal was being taken on board and cargo unloaded, and to escape the noise we had all gone ashore to pass the time in coffeehouses or theatres. It is my personal opinion however, that a number of conjectures which I did not voice publicly at the time provide the true explanation of that sensational event, and I think that, at a distance of some years, I may now be permitted to give an account of a conversation I had in confidence immediately before the curious episode.

When I went to the Calcutta shipping agency trying to book a passage on the Oceania for my voyage home to Europe, the clerk apologetically shrugged his shoulders. He didn’t know if it would be possible for him to get me a cabin, he said; at this time of year, with the rainy season imminent, the ship was likely to be fully booked all the way from Australia, and he would have to wait for a telegram from Singapore. Next day, I was glad to hear, he told me that yes, he could still reserve me a cabin, although not a particularly comfortable one; it would be below deck and amidships. As I was impatient to get home I did not hesitate for long, but took it.

The clerk had not misinformed me. The ship was over-crowded and my cabin a poor one: a cramped little rectangle of a place near the engine room, lit only dimly through a circular porthole. The thick, curdled air smelled greasy and musty, and I could not for a moment escape the electric ventilator fan that hummed as it circled overhead like a steel bat gone mad. Down below the engines clattered and groaned like a breathless coal-heaver constantly climbing the same flight of stairs, up above I heard the tramp of footsteps pacing the promenade deck the whole time. As soon as I had stowed my luggage away amidst the dingy girders in my stuffy tomb, I then went back on deck to get away from the place, and as I came up from the depths I drank in the soft, sweet wind blowing off the land as if it were ambrosia.

But the atmosphere of the promenade deck was crowded and restless too, full of people chattering incessantly, hurrying up and down with the uneasy nervousness of those forced to be inactive in a confined space. The arch flirtatiousness of the women, the constant pacing up and down on the bottleneck of the deck as flocks of passengers surged past the deckchairs, always meeting the same faces again, were actually painful to me. I had seen a new world, I had taken in turbulent, confused images that raced wildly through my mind. Now I wanted leisure to think, to analyse and organise them, make sense of all that had impressed itself on my eyes, but there wasn’t a moment of rest and peace to be had here on the crowded deck. The lines of a book I was trying to read blurred as the fleeting shadows of the chattering passengers moved by. It was impossible to be alone with myself on the unshaded, busy thoroughfare of the deck of this ship.

I tried for three days; resigned to my lot, I watched the passengers and the sea. But the sea was always the same, blue and empty, and only at sunset was it abruptly flooded with every imaginable colour. As for the passengers, after seventy-two hours I knew them all by heart. Every face was tediously familiar, the women’s shrill laughter no longer irritated me, even the loud voices of two Dutch officers quarrelling nearby were not such a source of annoyance any more. There was nothing for it but to escape the deck, although my cabin was hot and stuffy, and in the saloon English girls kept playing waltzes badly on the piano, staccato-fashion. Finally I decided to turn the day’s normal timetable upside down, and in the afternoon, having anaesthetized myself with a few glasses of beer, I went to my cabin to sleep through the evening with its dinner and dancing.

When I woke it was dark and oppressive in the little coffin of my cabin. I had switched off the ventilator, so the air around my temples felt greasy and humid. My senses were bemused, and it took me some minutes to remember my surroundings and wonder what the time was. It must have been after midnight, anyway, for I could not hear music or those restless footsteps pacing overhead. Only the engine, the breathing heart of the leviathan, throbbed as it thrust the body of the ship on into the unseen.

I made my way up to the deck. It was deserted. And as I looked above the steam from the funnel and the ghostly gleam of the spars, a magical brightness suddenly met my eyes. The sky was radiant, dark behind the white stars wheeling through it and yet radiant, as if a velvet curtain up there veiled a great light, and the twinkling stars were merely gaps and cracks through which that indescribable brightness shone. I had never before seen the sky as I saw it that night, glowing with such radiance, hard and steely blue, and yet light came sparkling, dripping, pouring, gushing down, falling from the moon and stars as if burning in some mysterious inner space. The white-painted outlines of the ship stood out bright against the velvety dark sea in the moonlight, while all the detailed contours of the ropes and the yards dissolved in that flowing brilliance; the lights on the masts seemed to hang in space, with the round eye of the lookout post above them, earthly yellow stars amidst the shining stars of the sky.

And right above my head stood the magical constellation of the Southern Cross, hammered into the invisible void with shining diamond nails and seeming to hover, although only the ship was really moving, quivering slightly as it made its way up and down with heaving breast, up and down, a gigantic swimmer passing through the dark waves. I stood there looking up; I felt as if I were bathed by warm water falling from above, except that it was light washing over my hands, mild, white light pouring around my shoulders, my head, and seeming to permeate me entirely, for all at once everything sombre about me was brightly lit.

1 comment