Part” in the center and Harvey, editor of the Review, wrote inclusive page numbers “199 to 242” at the top right. Paine, who in early 1907 helped Clemens prepare a section for publication in the Review, wrote in the top left corner, and later added (in blue pencil), “Copied for use”—referring to another typescript, TS3, prepared from this one to serve as printer’s copy for the excerpt, which was published in the Review for 19 April 1907 (NAR 16).

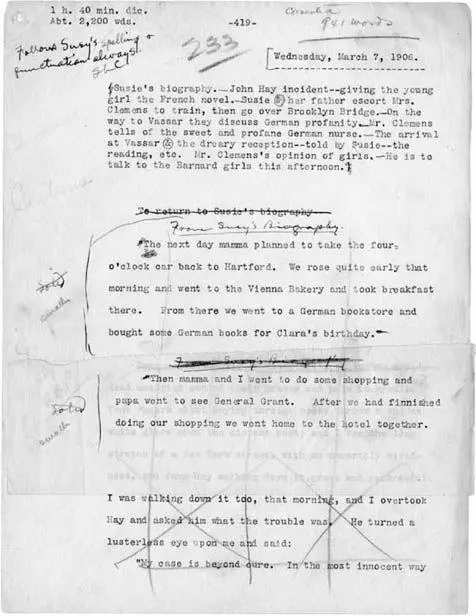

FIGURE 16. The first page of the Autobiographical Dictation of 7 March 1906 (TS1, 419). Clemens wrote “Follow Susy’s spelling & punctuation always. SLC” at the top left; inserted the head “From Susy’s Biography” (twice); and noted that the extracts were to be set “solid” (i.e., with reduced line spacing). Another typescript, TS3, was prepared from this one to serve as printer’s copy for an excerpt published in the Review for 16 November 1906 (NAR 6). The rest of the writing is by Paine, who used this typescript to prepare his 1924 edition (MTA, 2:166–72), from which he omitted all of page 420 and most of page 421. He cut a strip from the bottom of page 421 and pasted it to this page (covering part of the text), crossed out the second heading for Susy’s biography, and altered Clemens’s “solid” to “smaller.”

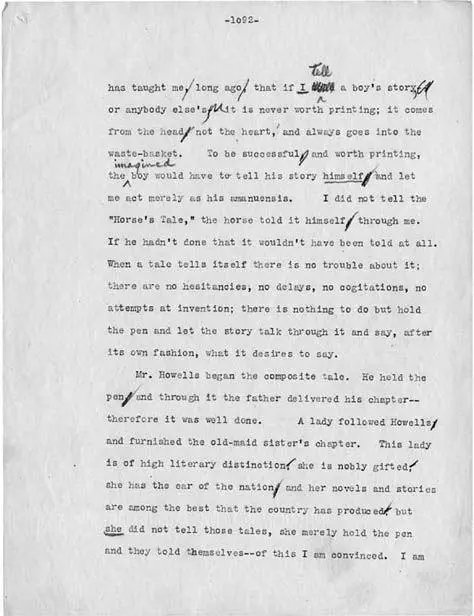

FIGURE 17. The fourth page of the Autobiographical Dictation of 29 August 1906 (TS1, 1092). All of the revisions are in pencil, but only some of them are Clemens’s: DeVoto added his own before he published the dictation in Mark Twain in Eruption (243). They can all be correctly identified by examining the text of TS4, which followed only Clemens’s markings, and DeVoto’s book, which followed all of them. Clemens made no changes in the punctuation; he wrote “tell” and “imagined,” and underlined “I,” “himself,” and “she” to italicize them.

These chapters should be issued soon in a little book. It would be a classic for a thousand years, & it could later be published in the large book. I am off to Chicago tomorrow & back on the 9th I wish I could print this wonderful thing in McClure’s Magazine. It would civilize a nation. It will uplift the Sunday press.

Finally, with Harvey’s return from England in mid-July, the troublesome Library of Humor problem was resolved and Clemens was able to return to Dublin on 25 July.88

Clemens had already published several essays in Harvey’s North American Review: “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” and “To My Missionary Critics” (1901) as well as his satirical commentary on Christian Science (1902–3). His first impulse had been to sell Harvey selections from the autobiography to go into Harper’s Weekly (which Harvey also edited), a much more widely read journal than the Review. But when Harvey finally made the twice-postponed visit to Dublin, arriving late on 31 July, he had big plans for the Review.89 He promptly immersed himself in the autobiography, and by the time he left Dublin on 4 August he and Clemens had agreed on what would become a sixteen-month series in the Review. “I like this arrangement,” Clemens confided to his friend Mary Rogers (Henry’s daughter-in-law), even as Harvey departed, “& so will Mr. Rogers; but he didn’t much like the idea of McClure’s newspaper syndicate, & I ceased to like it myself & stopped the negociations before I left New York.”90 As Clemens wrote to Clara on 3 August, he was impressed by Harvey’s “great plan: to turn the North American Review into a fortnightly the 1st of Sept, introduce into it a purely literary section, of high class, & in other ways make a great & valuable periodical of it.” He was also clearly flattered by Harvey’s response to his text:

He was always icily indifferent to the Autobiography before, but thought he would like to look at it now, so I told him to come up. He arrived 3 days ago, & has now carefully read close upon a hundred thousand words of it (there are 250,000). He says it is the “greatest book of the age,” & has in it “the finest literature.”

He has done some wonderful editing; for he has selected 5 instalments of 5,000 words each; & although these are culled from here & there & yonder, he has made each seem to have been written by itself—& without altering a word. At 10,000 words a month we shall place about 110,000 or 120,000 words before the public in 12 months. . . .

To-morrow Harvey will carry away one full set of the MSS to Howells & get him to help select instalments. I can’t do the selecting myself. The instalments will come to me in galley-proofs for approval, but I guess I will pass them on to you for final judgment after I have examined them.91

Not only did Harvey “carefully read close upon a hundred thousand words” of the autobiography’s 250,000, but by the time he left Dublin on 4 August he had read the remaining 150,000 words, encompassing the pre-1906 material and all the dictations through the end of June.92

A Composite Typescript: TS3

Harvey’s “wonderful editing” was exactly as Clemens characterized it: he selected excerpts and patched them together to create five installments, essentially without “altering a word.” Domestic anecdotes were a principal theme. He used the moving description of Olivia, and of Susy and her death, with nearly all the excerpts from Susy’s biography of her father that were quoted in the February and March dictations. Other favored topics included Clemens’s amusing misdeeds, such as his swearing about the missing shirt buttons; Susy’s charming eccentricities of spelling; Clemens’s puzzlement over the “spoon-shaped drive”; and the challenges of the burglar alarm at the Hartford house.

1 comment