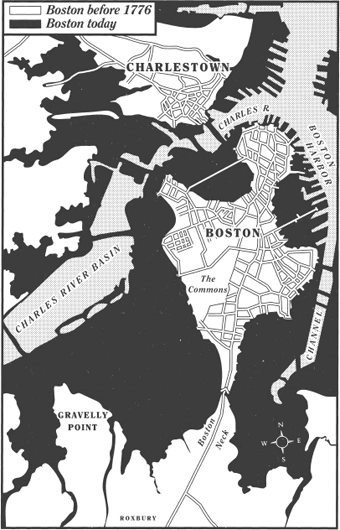

So return with him to old Boston, a place that for him was both familiar and fresh at the same time, because I wrote what I knew about Boston in the context of what I wanted to know about it.

William Martin

Boston, July 2012

October 1789

Horace Taylor Pratt pulled a silver snuffbox from his waistcoat pocket and placed it on the table in front of him. He hated snuffboxes. They were small, delicate, and nearly impossible for a man with one arm to open. Whenever he fumbled for snuff, Pratt cursed the two-armed world that conspired against him, but when he wanted a clear head, he had to have snuff. This evening, he wanted wits as sharp as a glasscutter.

He slid the box open, took a pinch of black powder, and brought it to his nose.

“Father!” The young voice cracked, and Pratt turned to his son, a handsome boy of thirteen. “You’re not going to sneeze in the presence of his majesty, are you, Father?”

Pratt looked around, his fingers poised theatrically just below his left nostril. “Majesty? I see no king, Horace.”

Two hundred of Boston’s most prominent citizens sat with the Pratts at a great, three-sided banquet table in Faneuil Hall. The gentlemen were dressed in their finest satins, brocades, broadcloths, and silks. The table was covered in Irish linen and laden with fruits and cheeses. Candles glowed against October’s early dusk. John Hancock’s personal stock of port filled crystal stemware. The guest of honor, seated between John Adams and Governor Hancock, was America’s most royal figure.

“I mean His Presidency.” Young Horace looked toward the middle of the table, where a hulking man with powdered hair chewed on a piece of cheddar while Hancock and Adams conversed around him. “You can’t take snuff in front of George Washington.”

Pratt leaned close to his son and whispered, “He looks rather bored sitting between those two Massachusetts magpies. I daresay he’d love a dash of snuff himself right now.”

Pratt inhaled the tobacco and took another pinch in his right nostril. He closed his eyes. He felt the tingle spread through his sinuses. His mouth opened, his back stiffened, and he reached for his handkerchief. Before he could cover his face, the sneeze burst out of him, and Washington jumped as though startled by a British musket. Pratt sneezed again, more violently. Conversation stopped all about the room. John Adams shot an angry glance at Pratt. Young Horace slumped in his chair and counted the stitches on the hem of the tablecloth. Pratt sneezed once more, a final, satisfied bark. Then he blew his nose and looked around. Every eye was on him.

When Horace Taylor Pratt wanted attention, no discreet clearing of the throat or subtle shuffling of the feet would do. He glanced toward the center of the table. Washington was still staring in his direction, and John Adams’s bald head was blushing crimson, the color of Washington’s satin frock.

Pratt stood quickly. “Before John Adams, in the high dudgeon for which he is famous, chides me for taking a bit of snuff, let me propose a toast.” He lifted his glass. “To the health of our Federal Republic and its new President.”

“Hear, hear,” grunted Mather Byles, the old Tory minister seated next to Pratt.

John Hancock raised his glass. John Adams lifted his crankily.

1 comment