Wrong again: for indubitably he does support himself, and that is the only unanswerable proof that any man can show of his possessing the means so to do. No more then. Since he will not quit me, I must quit him. I will change my offices; I will move elsewhere; and give him fair notice, that if I find him on my new premises I will then proceed against him as a common trespasser.

Acting accordingly, next day I thus addressed him: “I find these chambers too far from the City Hall; the air is unwholesome. In a word, I propose to remove my offices next week, and shall no longer require your services. I tell you this now, in order that you may seek another place.”

He made no reply, and nothing more was said.

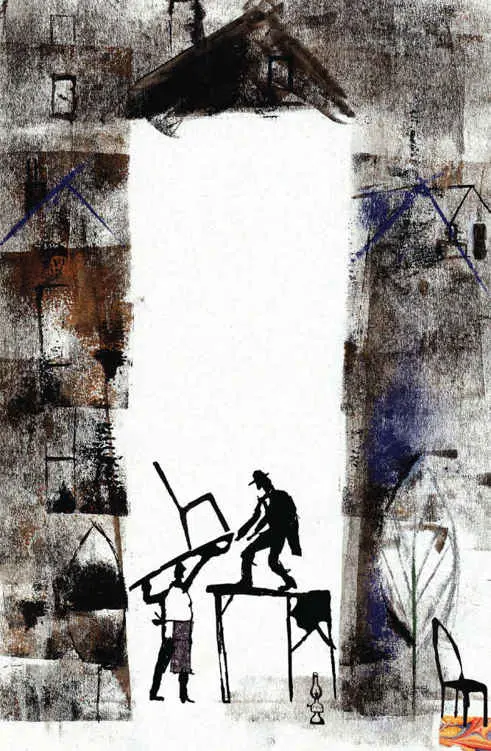

On the appointed day I engaged carts and men, proceeded to my chambers, and having but little furniture, every thing was removed in a few hours. Throughout, the scrivener remained standing behind the screen, which I directed to be removed the last thing. It was withdrawn; and being folded up like a huge folio, left him the motionless occupant of a naked room. I stood in the entry watching him a moment, while something from within me upbraided me.

I re-entered, with my hand in my pocket—and—and my heart in my mouth.

“Good-bye, Bartleby; I am going—good-bye, and God some way bless you; and take that,” slipping something in his hand. But it dropped upon the floor, and then,—strange to say—I tore myself from him whom I had so longed to be rid of.

Established in my new quarters, for a day or two I kept the door locked, and started at every footfall in the passages. When I returned to my rooms after any little absence, I would pause at the threshold for an instant, and attentively listen, ere applying my key. But these fears were needless. Bartleby never came nigh me.

I thought all was going well, when a perturbed looking stranger visited me, inquiring whether I was the person who had recently occupied rooms at No. — Wall-street.

Full of forebodings, I replied that I was.

“Then sir,” said the stranger, who proved a lawyer, “you are responsible for the man you left there. He refuses to do any copying; he refuses to do any thing; he says he prefers not to; and he refuses to quit the premises.”

“I am very sorry, sir,” said I, with assumed tranquillity, but an inward tremor, “but, really, the man you allude to is nothing to me—he is no relation or apprentice of mine, that you should hold me responsible for him.”

“In mercy’s name, who is he?”

“I certainly cannot inform you. I know nothing about him. Formerly I employed him as a copyist; but he has done nothing for me now for some time past.”

“I shall settle him then,—good morning, sir.”

Several days passed, and I heard nothing more; and though I often felt a charitable prompting to call at the place and see poor Bartleby, yet a certain squeamishness of I know not what withheld me.

All is over with him, by this time, thought I at last, when through another week no further intelligence reached me. But coming to my room the day after, I found several persons waiting at my door in a high state of nervous excitement.

“That’s the man—here he comes,” cried the foremost one, whom I recognized as the lawyer who had previously called upon me alone.

“You must take him away, sir, at once,” cried a portly person among them, advancing upon me, and whom I knew to be the landlord of No. — Wall-street. “These gentlemen, my tenants, cannot stand it any longer; Mr. B——” pointing to the lawyer, “has turned him out of his room, and he now persists in haunting the building generally, sitting upon the banisters of the stairs by day, and sleeping in the entry by night. Every body is concerned; clients are leaving the offices; some fears are entertained of a mob; something you must do, and that without delay.”

Aghast at this torrent, I fell back before it, and would fain have locked myself in my new quarters. In vain I persisted that Bartleby was nothing to me—no more than to any one else. In vain:—I was the last person known to have any thing to do with him, and they held me to the terrible account. Fearful then of being exposed in the papers (as one person present obscurely threatened) I considered the matter, and at length said, that if the lawyer would give me a confidential interview with the scrivener, in his (the lawyer’s) own room, I would that afternoon strive my best to rid them of the nuisance they complained of.

Going up stairs to my old haunt, there was Bartleby silently sitting upon the banister at the landing.

“What are you doing here, Bartleby?” said I.

“Sitting upon the banister,” he mildly replied.

I motioned him into the lawyer’s room, who then left us.

“Bartleby,” said I, “are you aware that you are the cause of great tribulation to me, by persisting in occupying the entry after being dismissed from the office?”

No answer.

“Now one of two things must take place. Either you must do something, or something must be done to you. Now what sort of business would you like to engage in? Would you like to re-engage in copying for some one?”

“No; I would prefer not to make any change.”

“Would you like a clerkship in a dry-goods store?”

“There is too much confinement about that. No, I would not like a clerkship; but I am not particular.”

“Too much confinement,” I cried, “why you keep yourself confined all the time!”

“I would prefer not to take a clerkship,” he rejoined, as if to settle that little item at once.

“How would a bar-tender’s business suit you? There is no trying of the eyesight in that.”

“I would not like it at all; though, as I said before, I am not particular.”

His unwonted wordiness inspirited me. I returned to the charge.

“Well then, would you like to travel through the country collecting bills for the merchants? That would improve your health.”

“No, I would prefer to be doing something else.”

“How then would going as a companion to Europe, to entertain some young gentleman with your conversation,—how would that suit you?”

“Not at all. It does not strike me that there is any thing definite about that.

1 comment