If the material does not cut upon itself, but allows the knot to be pulled taut, then it is suitable for rope making, providing that the material will ‘bite’ together and is not smooth or slippery.

You will find these qualities in all sorts of plants, in ground vines, in most of the longer grasses, in some of the water reeds and rushes, in the inner barks of many trees and shrubs, and in the long hair or wool of many animals.

Some green freshly gathered materials may be ‘stiff’ or unyielding. When this is the case try passing it through hot flames for a few moments. The heat treatment should cause the sap to burst through some of the cell structure, and the material thus becomes pliable.

Fibres for rope making may be obtained from many sources: Surface roots of many shrubs and trees have strong fibrous bark;

Dead inner bark of fallen branches of some species of trees and in the new growth of many trees such as willows;

In the fibrous material of many water and swamp growing plants and rushes;

In many species of grass and in many weeds;

In some sea weeds;

In fibrous material from leaves, stalks and trunks of many palms;

In many fibrous-leaved plants such as the aloes.

GATHERING AND PREPARATION OF MATERIALS

In some plants there may be a high content of vegetable gum and this can often be removed by soaking in water, or by boiling, or again, by drying the material and ‘teasing’ it into thin strips.

Some of the materials have to be used green it any strength is required. The materials that should be green include the sedges, water rushes, grasses, and lianas.

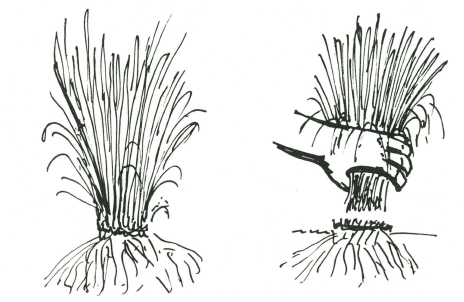

Grasses, sedges and water rushes should be cut and never pulled. Cutting above ground level is ‘harvesting,’ but pulling up the plant means its ‘destruction.’

It is advisable not to denude an area entirely but to work over a wide location and harvest the most suitable material, leaving some for seeding and further growth.

For the gathering of sedges and grasses, be particularly careful therefore to ‘harvest’ the material, that is, cut what you require above ground level, and take only from the biggest clumps.

By doing this you are not destroying the plant, but rather aiding the natural growth, since your harvesting is truly pruning.

You will find that from a practical point of view this is far the easiest method.

Many of the strong-leafed plants are deeply rooted, and you simply cannot pull a leaf off them.

Palm fibre in tropical or sub-tropical regions is harvested. You will find it at the junction of the leaf and the palm trunk, or you will find it lying on the ground beneath many palms. Palm fibre is a ‘natural’ for making ropes and cords.

Fibrous matter from the inner bark of trees and shrubs is generally more easily used if the plant is dead or half dead. Much of the natural gum will have dried out and when the material is being teased, prior to spinning, the gum or resin will fall out in fine powder.

There may be occasions when you will have to use the bark of green shrubs, but avoid this unless it is absolutely essential, and only cut a branch here and there. Never ever cut a complete tree just because you want the bark for a length of cord.

TO MAKE CORD BY SPINNING WITH THE FINGERS

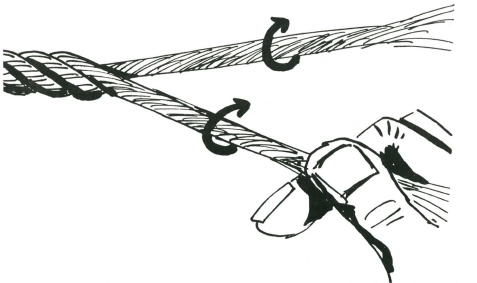

Use any material with long strong threads or fibres which you have previously tested for strength and pliability. Gather the fibres into loosely held strands of even thickness. Each of these strands is twisted clockwise. The twist will hold the fibre together. The strands should be from 1/8” downwards–for a rough and ready rule there should be about 15 to 20 fibres to a strand. Two, three or four of these strands are later twisted together, and this twisting together or ‘laying’ is done with an anti-clockwise twist, while at the same time the separate strands which have not yet been laid up are twisted clockwise. Each strand must be of equal twist and thickness.

This illustration shows the general direction of twist and the method whereby the fibres are bonded into strands. In similar manner the twisted strands are put together into lays, and the lays into ropes. Illustrated in this diagram is a two strand lay.

The person who twists the strands together is called the ‘layer,’ and he must see that the twisting is even, that the strands are uniform, and that the tension on each strand is equal. In laying, he must watch that each of the strands is evenly ‘laid up,’ that is, that one strand does not twist around the other two. (A thing you will find happening the first time you try to ‘lay up.’)

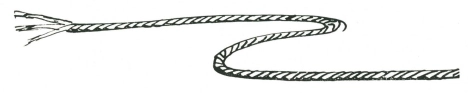

When spinning fine cords for fishing lines, snares, etc., considerable care must be taken to keep the strands uniform and the lay even. Fine thin cords of no more than one-thirty-second of an inch thickness can be spun with the fingers and they are capable of taking a breaking strain of twenty to thirty lbs. or more.

Normally two or more people are required to spin and lay up the strands for cord.

Many native people when spinning cord do so unaided, twisting the material by running the flat of the hand along the thigh, with the fibrous material between hand and thigh and with the free hand they feed in fibre for the next ‘spin.’ By this means one person can make long lengths of single stands.

This’ method of making cord or rope with the fingers is slow if any considerable length of cord is required.

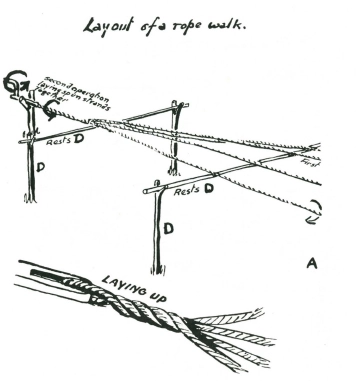

A more simple and easy way to rapidly make lengths of rope of fifty to a hundred yards or more in length is to make a rope-walk and set up multiple spinners in the form of cranks. The series of photographic illustrations on the succeeding pages show the details of rope spinning.

In a rope walk, each feeder holds the material under one arm and with one free hand feeds it into the strand which is being spun by the crank. The other hand lightly holds the fibres together till they are spun. As the lightly spun strands are increased in length they must be supported on cross bars. Do not let them lie on the ground. You can spin strands of twenty to one hundred yards before laying up. Do not spin the material in too thickly. Thick strands do not help strength in any way, rather they tend to make a weaker rope.

SETTING UP A ROPEWALK

When spinning ropes of ten yards or longer it is necessary to set cross bars every two or three yards to carry the strands as they are spun. If cross bars are not set up the strands or rope will sag to the ground, and some of the fibres will tangle up with grass, twigs or dirt on the ground. Also the twisting of the free end may either be stopped or interrupted and the strand will be unevenly twisted.

The easiest way to set up crossbars for the rope walk is to drive pairs of forked stakes into the ground about six feet apart and at intervals of about six to ten feet.

1 comment