He had left his father’s kingdom to have the pleasure of seeing and talking

to her.

Overjoyed to find her all alone, he spoke to her with great politeness and respect. After he had paid her all the ordinary compliments he saw that she was extremely sad, and said, “I

cannot understand, Madam, how a person as beautiful as you can be as sad as you seem to be. For although I can boast of having seen countless exquisitely charming ladies, I have never seen anyone

whose beauty compares to yours.”

“You are kind to say so,” answered the princess, and here she stopped, unable to think of anything else to say.

“Beauty,” said Riquet with the Tuft, “is such a great advantage, that it should make up for everything else, and since you possess this treasure, I can see nothing that would

trouble you.”

“I would much rather,” cried the princess, “be as ugly as you are, and have wit, than have all this beauty, and be as stupid as I am.”

“There is nothing, Madam,” he replied, “that shows that we have wit, more than to believe that we have none; and it is the nature of that excellent quality, that the more

people have of it, the more they believe they want it.”

“I do not know that,” said the princess, “but I know very well that I am very stupid, and this makes me so unhappy that I want to die.”

“If that is all that troubles you, Madam, I can very easily put an end to it.”

“And how will you do that?” cried the princess.

“I have the power, Madam,” replied Riquet with the Tuft, “to give to the person I love best, as much wit as anyone could have. As you are that very person, you will have as

great a share of it as anyone living, if you will agree to marry me.”

The princess was astonished, and said nothing at all (for she could not think of anything to say).

“I see,” said Riquet with the Tuft, “that this proposal makes you very uneasy, and I am not surprised, but I will give you a whole year to consider it.”

The princess had so little wit and, at the same time, so great a desire to have some, that she imagined the end of a year would never come, and she therefore accepted the proposal. She had no

sooner promised Riquet with the Tuft that she would marry him on that day the following year, than she found that she was completely changed, with an incredible ability to say whatever she wanted,

in a polite, easy and natural manner. She started a very interesting conversation with Riquet with the Tuft, during which she rattled on at such a rate that the prince began to believe that he had

given her more wit than he had kept for himself.

When the princess returned to the palace the court didn’t know what to think of this sudden and extraordinary change, for they now heard from her as much sensible conversation and as many

infinitely witty asides as they had heard stupid and silly remarks before. Everyone was overjoyed beyond belief – all except her younger sister, who, no longer having the advantage over her

of wit, seemed in comparison to be very disagreeable and plain.

The king began to take the advice of his older daughter and would even sometimes hold his council meetings in her apartment. The rumour of this change spread far and wide, and all the young

princes of the neighbouring kingdoms did their best to win her favour, and almost all of them proposed marriage to her. Not one of them had enough wit for her, and although she gave them all a

hearing, she would not get engaged to any of them.

However, one day a prince came along who was so powerful, witty, rich and handsome that the princess could not help being taken with him. Her father noticed it and told her that she could decide

for herself whom she wanted to marry and that she could declare her intentions towards this prince if she wished. However, the more wit we have, the more difficult we find it to make a decision in

such matters, so, having thanked her father, she asked him to give her time to consider the matter.

By chance, in order to think about what she should do, the princess went for a walk in the same wood where she had met Riquet with the Tuft. While she was walking, deep in thought, she heard the

confused noise under her feet of a great many people rushing about very busily. Listening more attentively, she heard one say, “Bring me that pot.” Then she heard another say,

“Give me that kettle,” and a third, “Put some wood on the fire.”

At the same time the ground opened and she saw under her feet a great kitchen full of cooks, maids and all sorts of servants necessary for a magnificent banquet. About 20 or 30 of them left the

kitchen to set up spits in a clearing around a very long table, with larding pins in their hands and skewers in their caps. They began to work, keeping time to a very melodious song.

The princess was amazed at this sight, and asked them who they worked for.

“For Prince Riquet with the Tuft,” was the reply, “who is to be married tomorrow.”

The princess was more surprised than ever, and when she remembered that it was a year to the day when she had promised to marry Riquet with the Tuft, she felt like sinking into the ground.

What had made her forget was that when she made the promise she was very silly, and having gained the vast stock of wit that Riquet with the Tuft had bestowed on her, she had completely

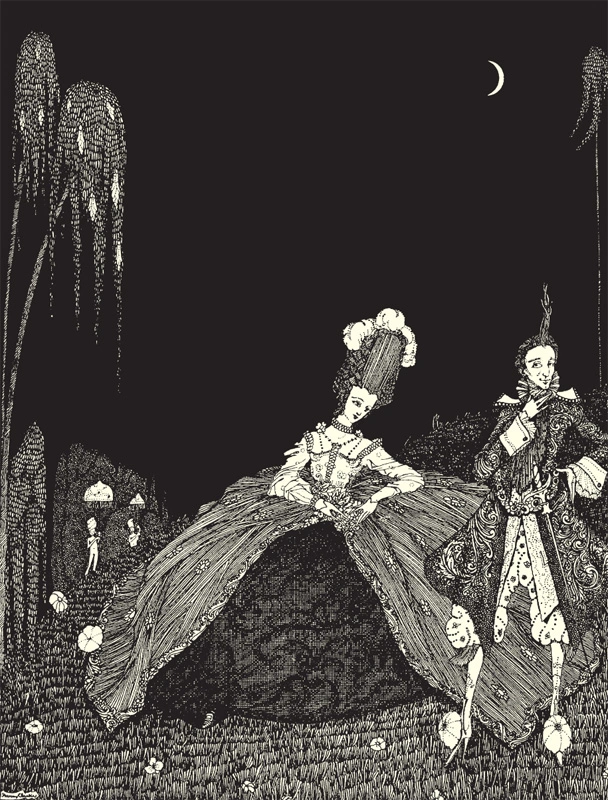

forgotten her stupidity. She went on her way, but had not taken more than 30 steps before Riquet with the Tuft presented himself to her, magnificently dressed, looking like a prince who was going

to be married.

“RIQUET WITH THE TUFT APPEARED TO HER THE FINEST PRINCE UPON EARTH”

“You see, Madam,” he said, “I am very precise at keeping my word, and do not doubt that you have come here to keep yours, and to make me, by marrying me, the happiest of

men.”

“I freely admit to you,” answered the princess, “that I have not yet made any decision about this, and I believe that I shall never make the one you wish for.”

“You astonish me, Madam,” said Riquet with the Tuft.

“I believe that,” said the princess, “and if I were dealing with a clown, or a stupid man, I would find myself very much at a loss. ‘A princess always observes her

word,’ he would say to me, ‘and you must marry me, since you promised to do so.’ But as I know you are a man of the world who is a master of sense and good judgement, I am sure

that you will listen to reason. You know that when I was just a fool I could never have decided to marry you. Why would you have me – now that I have as much judgement as you gave me and

which makes me a more difficult person than I was then – come to such a decision, when I was not able to do so at that time? If you sincerely wanted to make me your wife, you were very wrong

to deprive me of my stupid simplicity and make me see things more clearly than I did.”

“If a man of no wit or sense,” replied Riquet with the Tuft, “would be entitled, as you say, to reproach you for breaking your promise, why will you not let me do the same in a

matter that concerns all of the happiness in my life? Is it reasonable that people of wit and sense should be in a worse situation than those who have none? Can you pretend this, you who have so

much wit, and who wanted so much to have it? But let us speak of the facts. Putting aside my ugliness and deformity, is there anything about me that you don’t like? Are you put off by my

birth, wit, humour or manners?”

“Not at all,” answered the princess, “I love you and respect you in all these things.”

“If that is true,” said Riquet with the Tuft, “I will be very happy, since it is in your power to make me the most lovable of men.”

“How can that be?” asked the princess.

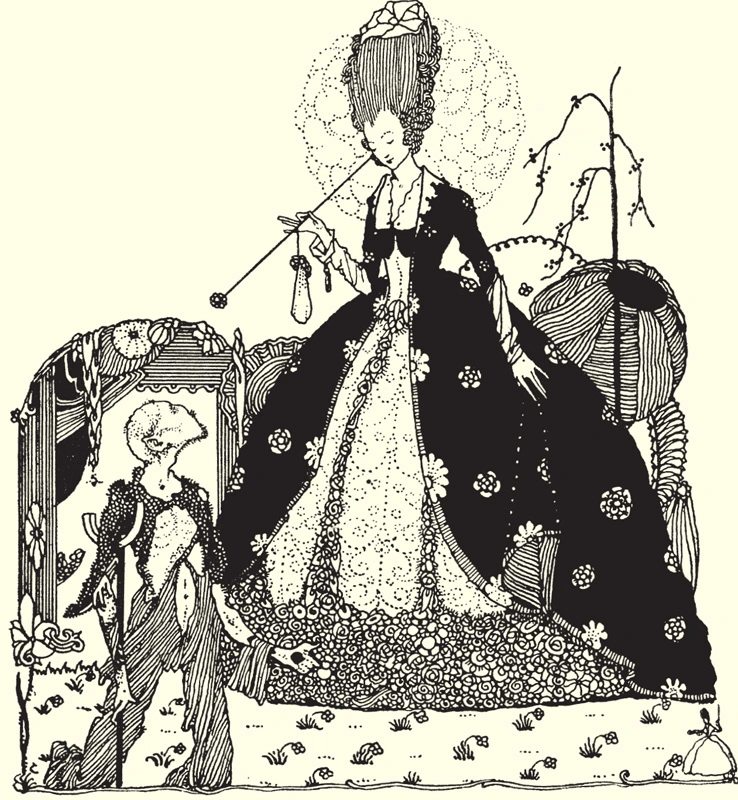

“It will come about,” said Riquet with the Tuft, “if you love me enough to want it. And so that you will not doubt what I say, you should know that the same fairy who, on my

birthday, gave me the power of making the person who pleased me extremely witty and judicious, has given you the power to make the man you love extremely handsome.”

“If that is the case,” said the princess, “I wish, with all my heart, that you may be the most lovable prince in the world, and I bestow it upon you.”

The princess had no sooner said these words, than Riquet with the Tuft appeared to her to be the finest prince upon the earth, the most handsome and amiable man she had ever seen. Some say it

was not the enchantments of the fairy that brought about this alteration, but that love alone caused the change. They say that the princess, having reflected on the perseverance of her lover, his

discretion, and all the good qualities of his mind, his wit and his judgement, no longer saw the deformity of his body or the ugliness of his face. His hump seemed to be no more than a broad back,

and that while until then she had seen him limp horribly, she now found that it was no more than his particular way of walking, which she found charming.

They also say that his eyes, which had squinted badly, seemed now all the brighter and more sparkling, that their unevenness seemed to her to be a sign of great love, and that his great red nose

had an air of the martial and heroic.

Whatever the reason, the princess promised to marry him, on condition that he obtained her father’s consent. The king knew his daughter well and had great esteem for Riquet with the Tuft,

who he knew to be a wise and judicious prince. He received him as his son-in-law with pleasure, and the next morning their marriage was celebrated, as Riquet with the Tuft had foreseen, and

according to the orders he had given a long time before.

THE MORAL

What in this little Tale we find,

Is less a fable than real truth.

In those we love appear rare gifts of mind,

And body too: wit, judgement, beauty, youth.

ANOTHER

A countenance whereon, by nature’s hand

Beauty is trac’d, also the lively stain

Of such complexion art can ne’er attain,

With all these gifts hath not so much command

On hearts, as hath one secret charm alone.

Love finds that out, to all besides unknown.

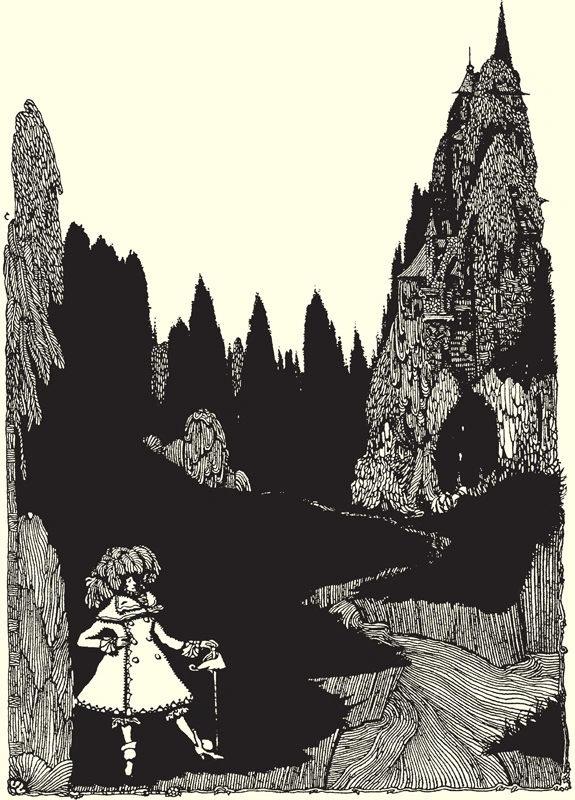

TOM THUMB

Once upon a time there was a woodcutter, who had a wife and seven children, all boys. The eldest was ten years old, and the youngest was seven

years of age. It might seem strange that the woodcutter had so many children in so short a time, but it was because his wife never gave birth to fewer than two children at a time. They were very

poor, and their seven children were a great burden to them, because not one of them was able to earn his keep. They were also very worried about the youngest child, who was very puny, and hardly

ever spoke, which they regarded as a sign of stupidity, although in this case it was actually an indication of good sense.

1 comment