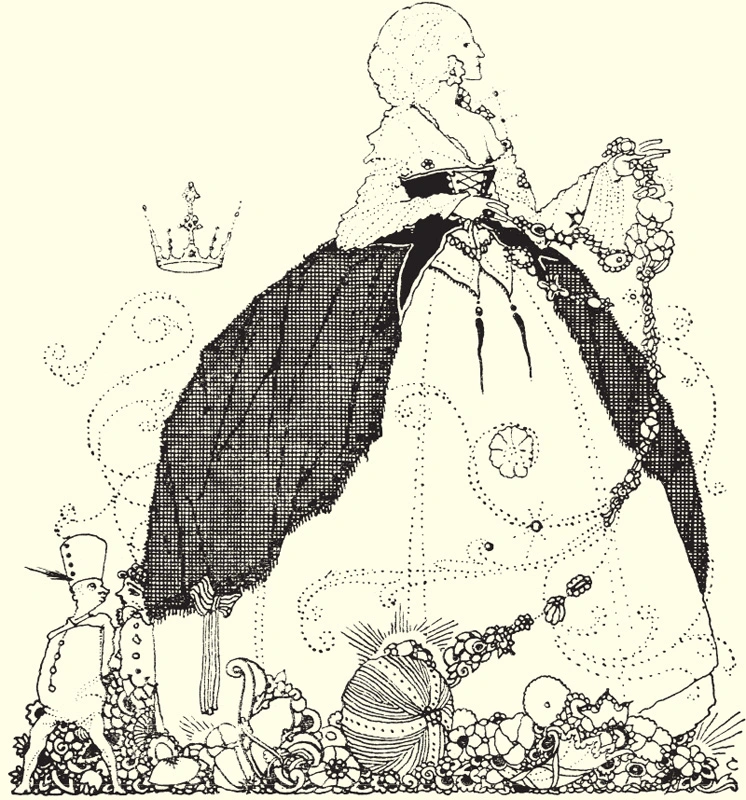

Of these, it seems that only one colour plate survives, ‘He Saw, Upon a Bed, the Finest Sight Was Ever Beheld’, bought in 2010 by the National Gallery of Ireland.

It is immediately clear that the colours have changed since the publication of the Hans Christian Andersen volume and the palette is now much more subtle. Silhouettes (see ‘Tom

Thumb’) are used to good effect, and there is even an overtly erotic element to some of the illustrations (see ‘Donkey Skin’ and ‘The Sleeping

Beauty’). Some of the characters are caricatures of Clarke’s contemporaries, although this is of little significance to today’s reader. This was a book for adults rather

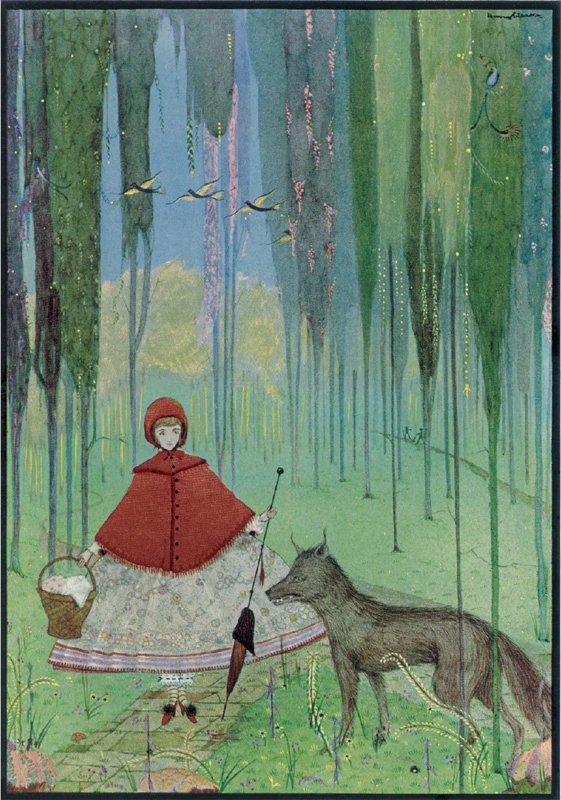

than children. Perrault’s tales, predating Andersen’s by about 150 years, are not the soft-focus sanitised versions with which later generations have become familiar. In ‘Little

Red Riding Hood’, for example, there is no happy resurrection of the child and her grandmother at the end of the story – they are eaten by the wolf and that’s the

last we see of them. In these often gently witty stories actions have consequences; characters are certainly rewarded for being good or beautiful or clever, but stupidity, even if well intended,

and even if allied with goodness and beauty, results in disaster. Perrault even appended a little moral verse (or two) to the end of each story, just to drive home his point.

‘HE SAW UPON A BED, THE FINEST SIGHT WAS EVER BEHELD’ Photo © NGI

Clarke seems to have tapped into the darker aspect of the stories – The English Review drew attention to the ‘unearthliness’ of the images – and there is a

menacing quality to many of the illustrations, playful and caricaturing though some of them are. By the time he was working on Perrault, Tales of Mystery & Imagination had been published

in two editions; perhaps Clarke thought the Perrault stories lent themselves to the approach he had employed in that series of illustrations. Unfortunately, The Fairy Tales of Perrault

failed to achieve the critical acclaim that had greeted the publication of the Andersen volume and sales were poor. According to Nicola Gordon Bowe, the ‘idiosyncratic and fantastic

detail’ of the illustrations ‘were perhaps too weird for a generation attuned to the illustrations of Rackham, Dulac and the Robinsons’.4

However, children today, inured to the weird and fantastic by television, film and computer games, may find the Perrault illustrations less disturbing than their predecessors might have done in the

1920s.

When he died in 1931, Clarke bequeathed a wealth of stained glass, both religious and secular, and a substantial list of illustrated publications. His windows live on, but many of his original

book illustrations were held at the Harrap offices in London and were burned during the Blitz. Others were destroyed during the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. Happily, the National Gallery of

Ireland holds one of his original Perrault illustrations and a number of the illustrations for Hans Christian Andersen.

Notes

1 ‘The Irish Symbolist’, The Irish Times, 10 December 1983.

2 George Russell, The Irish Statesman, 21 December 1929.

3 ‘The Art of Mr Harry Clarke’, The Studio, November 1919, p.46.

4 Nicola Gordon Bowe, The Life and Work of Harry Clarke (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1989), p.145.

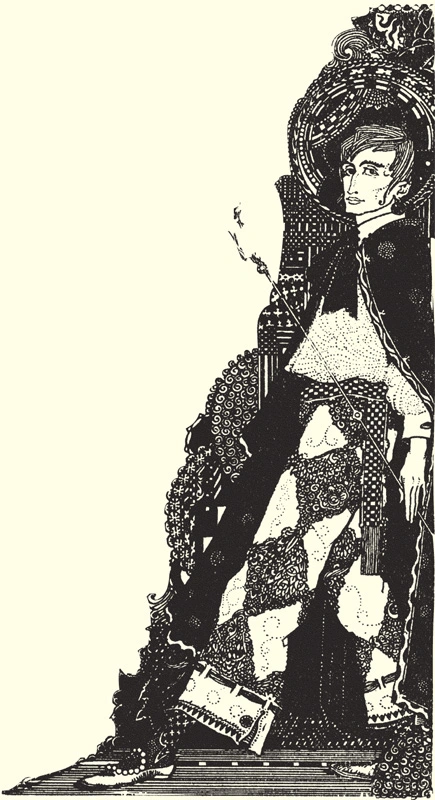

Drawing by Clarke, thought to be a self-portrait.

LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD

Once upon a time, in a country village, there lived the prettiest little girl you have ever seen. Her mother loved her very much, and her

grandmother doted on her even more. The old woman had a little red cape with a hood made for the child; this suited her so well that people in the neighbourhood began to call her Little Red Riding

Hood.

One day, her mother had been making some bread. She said to Little Red Riding Hood, “Why don’t you go to see how your grandmother is, for I hear that she has been very ill. Take her

one of my loaves of bread and this little pot of butter.”

Little Red Riding Hood set out at once to visit her old grandmother, who lived in another village. As she was going through the woods she met a big wolf, who would have liked to eat her up, but

didn’t dare, because there were some woodmen at work in the forest nearby.

The wolf asked Little Red Riding Hood where she was going. The poor child, who didn’t know that it was dangerous to stop and talk to a wolf, said, “I am going to see my grandmother,

and am taking her a loaf of bread and some butter, from my mother.”

“Does she live far away?” asked the wolf

“Oh, yes,” answered Little Red Riding Hood, “she lives just beyond that mill, in the first house in the village.”

“Well,” said the wolf, “I think I’ll go and see her, too. I’ll go this way and you go that, and we’ll see who gets there first.”

The wolf began to run as fast as he could, taking the shortest way to the grandmother’s house; and the little girl went by the longest way, dawdling along the road and amusing herself by

gathering nuts, running after butterflies and making posies of wild flowers. It wasn’t long before the wolf reached the old woman’s house. He knocked on the door, tap, tap.

“Who’s there?”

“Your granddaughter, Little Red Riding Hood,” replied the wolf, imitating the little girl’s voice. “I have brought you a loaf of bread and a little pot of butter, sent to

you by my mother.”

The good woman, who was in bed because she still wasn’t feeling very well, called out,

“Pull the latch, and the door will open.”

The wolf pulled the latch, and the door opened. He jumped on the good woman and ate her up in a moment, for it was more than three days since he had had anything to eat. He then shut the door

and climbed into the grandmother’s bed to wait for Little Red Riding Hood, who came along some time afterwards and knocked on the door, tap, tap.

“Who’s there?”

Little Red Riding Hood, hearing the big voice of the wolf, was afraid; then, believing that her grandmother’s cold had made her hoarse, answered,

“It’s your granddaughter, Little Red Riding Hood, who has brought you a loaf of bread and some butter, sent by my mother.”

The wolf called out to her, softening his voice as much as he could,

“Pull the latch, and the door will open.”

Little Red Riding Hood pulled the latch, and the door opened. When the wolf saw her come in, he hid himself under the bedclothes and said to her,

“Put the bread and the little pot of butter on the bread bin, and come and lie down with me.”

Little Red Riding Hood undressed herself and got into bed. She was very surprised to see how her grandmother looked in her nightdress and said to her, “Grandma, what big arms you’ve

got!”

“All the better to hug you with, my dear.”

“Grandma, what big legs you’ve got!”

“All the better to run with, my child.”

“Grandma, what big ears you’ve got!”

“All the better to hear with, my child!”

“Grandma, what big eyes you’ve got!”

“All the better to see with, my child.”

“Grandma, what great teeth you’ve got!”

“All the better to eat you up.”

And, saying these words, the wicked wolf fell on poor Little Red Riding Hood and ate her all up.

“THE WOLF ASKED LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD WHERE SHE WAS GOING”

THE MORAL

From this short story we discern

What conduct all young people ought to learn.

But above all, young, growing misses fair,

Whose orient rosy blooms begin t’appear:

Who, beauties in the fragrant spring of age,

With pretty airs young hearts are apt t’engage.

Ill do they listen to all sorts of tongues,

Since some enchant and lure like Syrens’ songs.

No wonder therefore ‘tis, if over-power’d,

So many of them has the Wolf devour’d.

The Wolf, I say, for Wolves too sure there are

Of every sort, and every character.

Some of them mild and gentle-humour’d be,

Of noise and gall, and rancour wholly free;

Who tame, familiar, full of complaisance

Ogle and leer, languish, cajole and glance;

With luring tongues and language wond’rous sweet,

Follow young ladies as they walk the street,

Ev’n to their very houses, nay, bedside,

And, artful, tho’ their true designs they hide;

Yet ah! These simpering Wolves! Who does not see

Most dangerous of Wolves indeed they be?

THE FAIRY

Once upon a time there was a widow who had two daughters. The eldest daughter was so much like her mother in appearance and temperament that

anyone who looked at the daughter saw the mother. They were both so unpleasant and snobbish that there was no living with them.

1 comment