Classic ghost stories

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

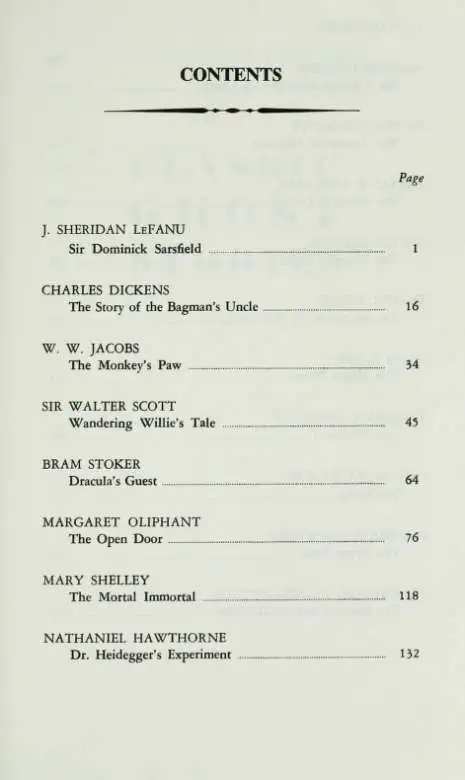

vi CONTENTS

Page CHARLES DICKENS

No. 1 Branch Line, the Signalman 142

SIR WALTER SCOTT

The Tapestried Chamber _ 155

AMELIA B. EDWARDS

The Phantom Coach 169

WILKIE COLLINS

The Dream Woman 183

DANIEL DEFOE

The Apparition of Mrs. Veal „ 207

BRAM STOKER

The Judge's House _ 211

FREDERICK MARRY AT

The Werewolf 229

GUY DE MAUPASSANT

The Horla _ _...._ _...._ 249

F. MARION CRAWFORD

The Upper Berth _ _ 272

SIR EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON

CLASSIC

GHOST

STORIES

SIR DOMINICK SARSFIELD

J. SHERIDAN LeFANU

IN the early autumn of the year 1838, business called me to the south of Ireland. The weather was delightful, the scenery and people were new to me, and sending my luggage on by the mail-coach route in charge of a servant, I hired a serviceable nag at a posting-house, and, full of the curiosity of an explorer, I commenced a leisurely journey of five-and-twenty miles on horseback, by sequestered crossroads, to my place of destination. By bog and hill, by plain and ruined castle, and many a winding stream, my picturesque road led me.

I had started late, and having made little more than half my journey, I was thinking of making a short halt at the next convenient place, and letting my horse have a rest and a feed, and making some provision also for the comforts of his rider.

It was about four o'clock when the road, ascending a gradual steep, found a passage through a rocky gorge between the abrupt termination of a range of mountains to my left and a rocky hill that rose dark and sudden at my right. Below me lay a little thatched village, under a long line of gigantic beech trees, through the boughs of which the lowly chimneys sent up their thin turf-smoke. To my left, stretched away for miles, ascending the mountain range I have mentioned, a wild park, through whose sward and ferns the rock broke, time-worn and lichen-stained. This park was studded with straggling wood, which thickened to something like a forest, behind and beyond the little village I was approaching, clothing the irregular ascent of the hillsides with beautiful, and in some places, discoloured foliage.

As you descend, the road winds slightly, with the grey park-wall, built of loose stone, and mantled here and there with ivy, at its left, and crosses a shallow ford; and as I approached the village, through breaks in the woodlands, I caught glimpses of the long front of an old ruined house, placed among the trees, about half-way up the picturesque mountain-side.

2 J. SHERIDAN LeFANU

The solitude and melancholy of this ruin piqued my curiosity, and when I had reached the rude thatched public house, with the sign of St. Columbkill, with robes, mitre, and crozier displayed over its lintel, having seen to my horse and made a good meal myself on a rasher and eggs, I began to think again of the wooded park and the ruinous house, and resolved on a ramble of half an hour among its sylvan solitudes.

The name of the place, I found, was Dunoran; and beside the gate a stile admitted to the grounds, through which, with a pensive enjoyment, I began to saunter towards the dilapidated mansion.

A long grass-grown road, with many turns and windings, led up to the old house, under the shadow of the wood.

The road as it approached the house skirted the edge of a precipitous glen, clothed with hazel, dwarf-oak, and thorn, and the silent house stood with its wide-open hall-door facing this dark ravine, the further edge of which was crowned with towering forest; and great trees stood about the house and its deserted courtyard and stables.

I walked in and looked about me, through passages overgrown with nettles and weeds; from room to room with ceilings rotted, and here and there a great beam dark and worn, with tendrils of ivy trailing over it. The tall walls with rotten plaster were stained and mouldy, and in some rooms the remains of decayed wainscoting crazily swung to and fro. The almost sashless windows were darkened also with ivy, and about the tall chimneys the jackdaws were wheeling, while from the huge trees that overhung the glen in sombre masses at the other side, the rooks kept up a ceaseless cawing.

As I walked through these melancholy passages—peeping only into some of the rooms, for the flooring was quite gone in the middle, and bowed down toward the centre, and the house was very nearly un-roofed, a state of things which made the exploration a little critical—I began to wonder why so grand a house, in the midst of scenery so picturesque, had been permitted to go to decay; I dreamed of the hospitalities of which it had long ago been the rallying place, and I thought what a scene of Redgauntlet revelries it might disclose at midnight.

The great staircase was of oak, which had stood the

SIR DOMINICK SARSFIELD 3

weather wonderfully, and I sat down upon its steps, musing vaguely on the transitoriness of all things under the sun.

Except for the hoarse and distant clamour of the rooks, hardly audible where I sat, no sound broke the profound stillness of the spot. Such a sense of solitude I have seldom experienced before. The air was stirless, there was not even the rustle of a withered leaf along the passage. It was oppressive. The tall trees that stood close about the building darkened it, and added something of awe to the melancholy of the scene.

In this mood I heard, with an unpleasant surprise, close to me, a voice that was drawling, and, I fancied, sneering, repeat the words: " Food for worms, dead and rotten; God over all."

There was a small window in the wall, here very thick, which had been built up, and in the dark recess of this, deep in the shadow, I now saw a sharp-featured man, sitting with his feet dangling. His keen eyes were fixed on me, and he was smiling cynically, and before I had well recovered my surprise, he repeated the distich:

" If death was a thing that money could buy, The rich they would live, and the poor they would die"

" It was a grand house in its day, sir," he continued, " Dunoran House, and the Sarsfields. Sir Dominick Sarsfield was the last of the old stock. He lost his life not six foot away from where you are sitting."

As he thus spoke he let himself down, with a little jump, on to the ground.

He was a dark-faced, sharp-featured, little hunchback, and had a walking-stick in his hand, with the end of which he pointed to a rusty stain in the plaster of the wall.

" Do you mind that mark, sir? " he asked.

" Yes," I said, standing up, and looking at it, with a curious anticipation of something worth hearing.

" That's about seven or eight feet from the ground, sir, and you'll not guess what it is."

" I dare say not," said I, " unless it is a stain from the weather."

" 'Tis nothing so lucky, sir," he answered, with the same cynical smile and a wag of his head, still pointing at the

4 J. SHERIDAN LeFANU

mark with his stick. " That's a splash of brains and blood. It's there this hundhred years; and it will never leave it while the wall stands."

" He was murdered, then? "

" Worse than that, sir," he answered.

" He killed himself, perhaps? "

" Worse than that, itself, this cross between us and harm! I'm oulder than I look, sir; you wouldn't guess my years."

He became silent, and looked at me, evidently inviting a guess.

" Well, I should guess you to be about five-and-fifty."

He laughed, and took a pinch of snuff, and said:

" I'm that, your honour, and something to the back of it. I was seventy last Candlemas. You would not a' thought that, to look at me."

" Upon my word, I should not; I can hardly believe it even now. Still, you don't remember Sir Dominick Sarsfield's death? " I said, glancing up at the ominous stain on the wall.

" No, sir, that was a long while before I was born. But m)'^ grandfather was butler here long ago, and many a time I heard tell how Sir Dominick came by his death. There was no masther in the great house ever since that happened.

1 comment