The Crisis Reader: Stories, Poems, and Essays from the NAACP’s Crisis Magazine. New York: Random House, 1999.

———, ed. In Search of Democracy: The NAACP Writings of James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, and Roy Wilkins (1920-1977). New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Wohlforth, Robert. “Dark Leader: James Weldon Johnson.” The New Yorker, September 30, 1933, 20-24.

Young, James O. Black Writers of the Thirties. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1973.

COLLECTIONS

The James Weldon Johnson Papers in the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters, Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

The James Weldon Johnson Papers in African-American Collections, Woodruff Library, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

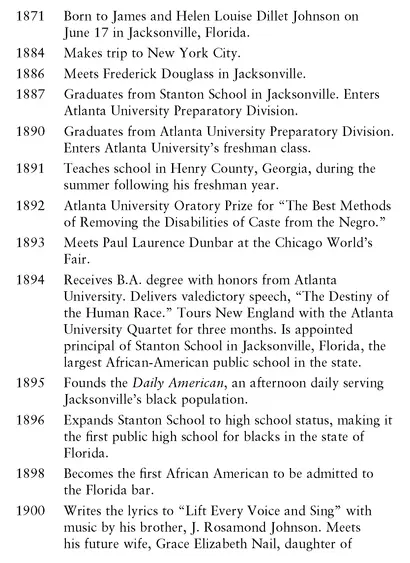

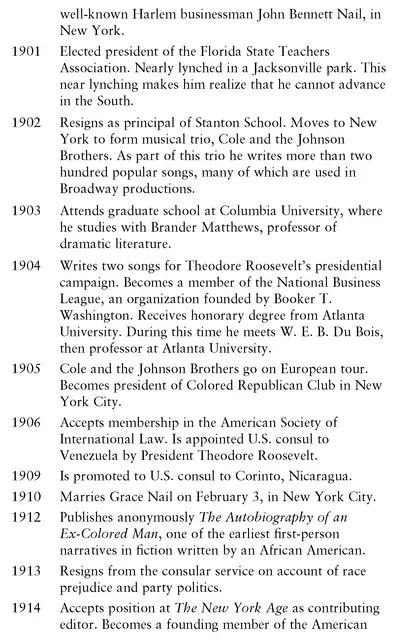

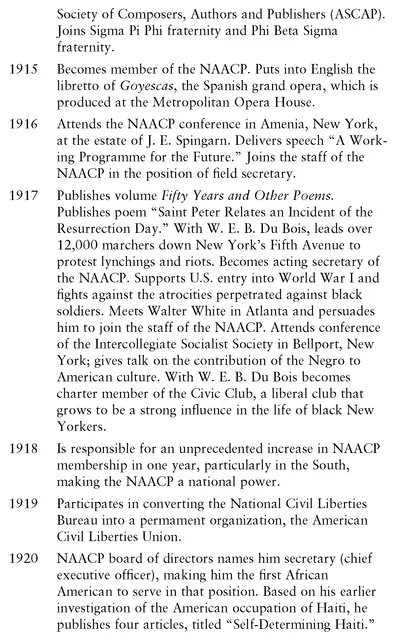

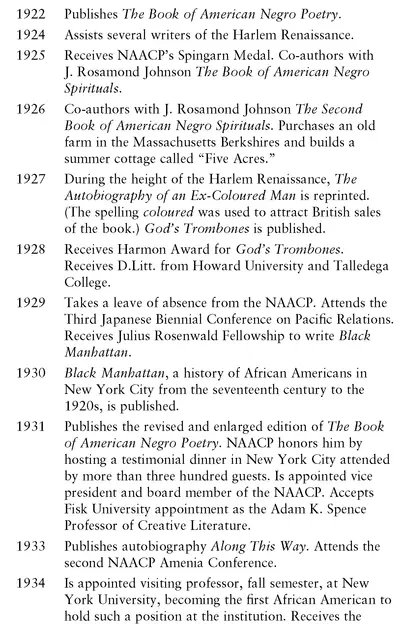

CHRONOLOGY

*Mrs. James Weldon Johnson (Grace Nail Johnson) died on November 1, 1976. Grace and James Weldon Johnson were interred together by Ollie Jewel Sims Okala on November 19, 1976, in the Nail family plot in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

PART I

God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse

JAMES WELDON JOHNSON’s search for an African-American tradition in American literature was initially unintentional. Born into a sedate family steeped in European values, he ultimately stumbled upon another world replete with “black mass” values. It was this discovery that led him to the hidden treasure of black folk art.

The revelation that brought about his transformation regarding black poetry came by way of an old-time Kansas City preacher. This sermonizer inspired Johnson’s poem “The Creation,” which was first published in 1918. Johnson writes about the preacher’s influence upon him, “The preacher strode the pulpit up and down in what was actually a rhythmic dance and he brought into play a full gamut of his wonderful voice which excited my envy. He intoned, he moaned, he pleaded—he blared, he crashed, he thundered.” Deeply moved, Johnson took out a slip of paper and began writing the poem “The Creation.” This poem, extracted from the oral folk tradition, represents the documentation of a people’s culture. In 1927 Johnson published “The Creation” with six other poems under the title God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. In this volume he transformed the old-time preachers’ orations into original and moving poetry, and in doing so, ensured the survival of a people’s great oral tradition.

Preface

A GOOD DEAL has been written on the folk creations of the American Negro: his music, sacred and secular; his plantation tales, and his dances; but that there are folk sermons, as well, is a fact that has passed unnoticed. I remember hearing in my boyhood sermons that were current, sermons that passed with only slight modifications from preacher to preacher and from locality to locality. Such sermons were, “The Valley of Dry Bones,” which was based on the vision of the prophet in the 37th chapter of Ezekiel; the “Train Sermon,” in which both God and the devil were pictured as running trains, one loaded with saints, that pulled up in heaven, and the other with sinners, that dumped its load in hell; the “Heavenly March,” which gave in detail the journey of the faithful from earth, on up through the pearly gates to the great white throne. Then there was a stereotyped sermon which had no definite subject, and which was quite generally preached; it began with the Creation, went on to the fall of man, rambled through the trials and tribulations of the Hebrew Children, came down to the redemption by Christ, and ended with the Judgment Day and a warning and an exhortation to sinners. This was the framework of a sermon that allowed the individual preacher the widest latitude that could be desired for all his arts and powers. There was one Negro sermon that in its day was a classic, and widely known to the public. Thousands of people, white and black, flocked to the church of John Jasper in Rich mond, Virginia, to hear him preach his famous sermon proving that the earth is flat and the sun does move. John Jasper’s sermon was imitated and adapted by many lesser preachers.

I heard only a few months ago in Harlem an up-to-date version of the “Train Sermon.” The preacher styled himself “Son of Thunder”—a sobriquet adopted by many of the old-time preachers—and phrased his subject, “The Black Diamond Express, running between here and hell, making thirteen stops and arriving in hell ahead of time.”

The old-time Negro preacher has not yet been given the niche in which he properly belongs. He has been portrayed only as a semi-comic figure. He had, it is true, his comic aspects, but on the whole he was an important figure, and at bottom a vital factor. It was through him that the people of diverse languages and customs who were brought here from diverse parts of Africa and thrown into slavery were given their first sense of unity and solidarity. He was the first shepherd of this bewildered flock. His power for good or ill was very great. It was the old-time preacher who for generations was the mainspring of hope and inspiration for the Negro in America. It was also he who instilled into the Negro the narcotic doctrine epitomized in the Spiritual, “You May Have All Dis World, But Give Me Jesus.” This power of the old-time preacher, somewhat lessened and changed in his successors, is still a vital force; in fact, it is still the greatest single influence among the colored people of the United States.

1 comment