Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe

THE COMPLETE WORKS OF

EDGAR ALLAN POE

(1809-1849)

Contents

The Poetry Collections

TAMERLANE AND OTHER POEMS

AL AARAAF, TAMERLANE AND MINOR POEMS

POEMS, 1831

THE RAVEN AND OTHER POEMS

UNCOLLECTED POEMS

The Poems

LIST OF POEMS IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

LIST OF POEMS IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER

The Tales

THE COMPLETE TALES IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

THE COMPLETE TALES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER

The Novels

THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM OF NANTUCKET

THE JOURNAL OF JULIUS RODMAN

The Play

POLITIAN

The Essays

INDEX OF THE COMPLETE ESSAYS

The Non-Fiction

THE CONCHOLOGIST’S FIRST BOOK

THE LITERATI

MARGINALIA

FIFTY SUGGESTIONS

A CHAPTER ON AUTOGRAPHY

The Letters

INDEX OF CORRESPONDENTS

INDEX OF CORRESPONDENTS, LETTERS AND DATES

The Criticism

EDGAR A. POE by James Russell Lowell.

AN EXTRACT FROM ‘FIGURES OF SEVERAL CENTURIES’ by Arthur Symons

AN EXTRACT FROM ‘LETTERS TO DEAD AUTHORS’ by Andrew Lang

THE CENTENARY OF EDGAR ALLAN POE by Edmund Gosse

FROM POE TO VALÉRY by T.S. Eliot

The Biographies

THE STORY OF EDGAR ALLAN POE by Sherwin Cody

THE DREAMER by Mary Newton Stanard

MEMOIR OF THE AUTHOR by Rufus Wilmot Griswold

DEATH OF EDGAR A. POE. by N. P. Willis

© Delphi Classics 2012

Version 6

THE COMPLETE WORKS OF

EDGAR ALLAN POE

By Delphi Classics, 2012

Interested in Gothic literature?

Then you’ll love these eBooks:

The Poetry Collections

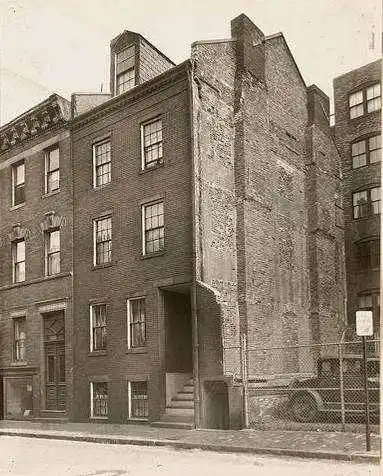

Edgar Allan Poe’s birthplace, Carver Street, Boston

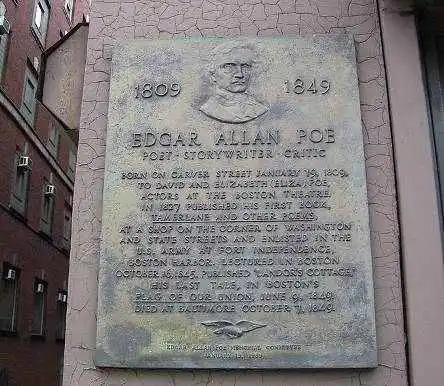

The plaque that marks where Poe was born

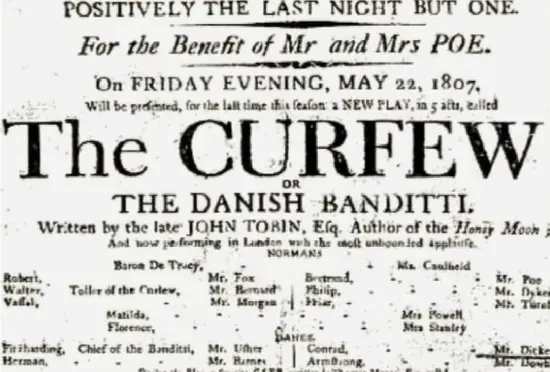

Eliza Poe, the author’s mother, who was actress.

Very little is known of the author’s father David, an actor who abandoned his family

shortly after Edgar’s birth. This play bill contains both of Poe’s parents’ names.

TAMERLANE AND OTHER POEMS

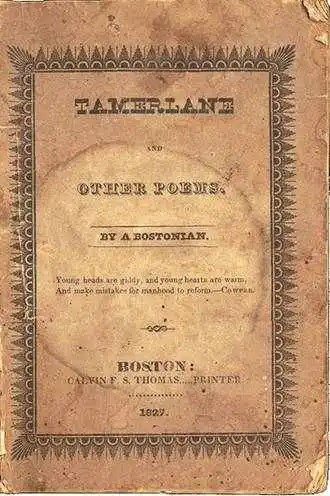

Poe’s first published work was a short collection of poems, which appeared in 1827

under the title Tamerlane and Other Poems. At the time, Poe had abandoned his foster family and moved to Boston to seek work.

Unsuccessful in finding suitable employment, the poet enlisted in the United States

Army. He brought with him several manuscripts, which he paid a printer named Calvin

F. S. Thomas to publish. The 40 page collection did not include Poe’s name and there

were only 50 copies printed, 12 of which still survive. The collection received no

critical attention.

The poems were largely inspired by Lord Byron, including the long title poem Tamerlane, which portrays an historical conqueror that laments the loss of his first romance.

Like much of Poe’s future work, the poems in Tamerlane and Other Poems include themes of love, death, and pride.

John and Frances Allan — Poe’s wealthy foster parents, who provided for him after

his mother’s early death from tuberculosis

The first edition cover of Poe’s first book of poetry

CONTENTS

TAMERLANE (1827)

FUGITIVE PIECES.

TO — —

DREAMS.

VISIT OF THE DEAD.

EVENING STAR.

IMITATION.

COMMUNION WITH NATURE

A WILDER’D BEING FROM MY BIRTH

THE HAPPIEST DAY — THE HAPPIEST HOUR

THE LAKE.

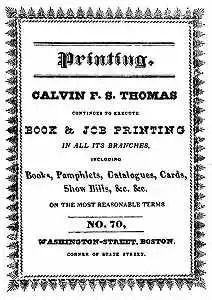

This advertisement was printed on the back cover of the booklet

PREFACE BY THE EDITOR.

THE same year that witnessed the publication, at Louth in Lincolnshire, of Alfred

Tennyson’s first schoolboy volume of verse also gave birth, at that literary capital

of the United States of America which takes its name from another Lincolnshire town,

to Edgar Poe’s maiden book. Unlike the sumptuous and elegant “Poems by Two Brothers,”

however, which the adventurous publishers actually had the temerity to issue in large-paper

form as well as in the ordinary size, Edgar Poe’s volume (if it can be dignified with

that designation) is the tiniest of tomes, numbering, inclusive of title and half-titles,

only forty pages, and measuring 6⅜ by 4⅛ inches. Its diminutiveness, probably quite

as much as the fact that it was “suppressed through circumstances of a private nature,”

accounts for its almost entire disappearance. The motto on the title-page purports

to be from Cowper: that from Martial, which closes the Preface (Nos hæc novimus esse nihil), was, by a curious coincidence, the very same that figured on the title-page of

Alfred and Charles Tennyson’s Louth volume.

In 1827, when the little “Tamerlane” booklet was thus modestly ushered into the world,

Poe had not yet attained his nineteenth year. Both in promise and in actual performance,

it may claim to rank as the most remarkable production that any English-speaking and

English-writing poet of this century has published in his teens.

In this earliest form of it the poem which gives its chief title to the little volume

is divided into seventeen sections, of irregular length, containing a total of 406

lines. “Tamerlane” was afterwards remodelled and rewritten, from beginning to end,

and in its final form, as it appeared in the author’s

edition of 1845, is divided into twenty-three sections, containing a total of 243

lines. Eleven explanatory prose notes are added, which disappear in all subsequent

editions. A critic whose familiar acquaintance with the text of Poe gives weight to

his verdict, declares that although “different in structure, and explaining some things

which, in later copies, are left to the imagination, the Tamerlane of 1827 is in many

parts quite equal to the present poem.”

Of the nine “Fugitive Pieces” which follow only three, and these in a somewhat altered

form, were included by the author in his later collection. The remaining six have

never been reprinted in book form, although they were, together with a few extracts

from the earliest version of “Tamerlane,” printed (so incorrectly, however, as to

be practically valueless,) in a magazine article on “The Unknown Poetry of Edgar Poe,”

contributed by Mr. John H. Ingram to Belgravia for June 1876.

I have no desire to disparage or underrate, and have already taken occasion to render

tribute to, the worthy and loyal service and labour of love performed by Mr. Ingram,

with zeal if not always with discretion, on the text of Poe, and still more notably

in clearing his life and memory from the aspersions of contemporary calumniators.

But, in justice both to myself and to others, I am compelled to repudiate and refute

the untenable and, as it seems to me, preposterous claim recently put forward by him

in the columns of a leading literary journal, to be the discoverer of the first edition

of Poe’s Tamerlane, and to possess a sort of moral right of monopoly over it.

The facts are simply these, and had I been allowed, as in all fairness I ought to

have been, to disclose them in the columns of the journal which gave insertion to

Mr. Ingram’s ex parte statement, I need not have troubled the reader with them here. First as to discovery.

The only copy of Edgar Poe’s 1827 volume at present known to have escaped destruction,

came into the possession of the British Museum on the 10th October 1867, which date

is (according to custom) officially impressed in red, at the end of the volume, i.e., at the bottom of page 40, under the last note. I believe I am correct in stating

that Mr. Ingram did not commence his work on the text of Poe until several years after

this: it was certainly not until nearly nine years after that he communicated to the

public his account of the “Tamerlane” volume, with extracts, first to Belgravia for June, 1876, and afterwards to the Athenæum for July 29, 1876. The extracts in the Athenæum were limited to four lines of verse, and an imperfect transcript of the title; but

the paper in Belgravia contained copious extracts from the longer poem of “Tamerlane,” and of the nine “fugitive

pieces,” the six suppressed ones were given in extenso.

1 comment