] so tired, so weary,

The soft head bows, the sweet eyes close,

The faithful heart yields to repose.

DEEP IN EARTH

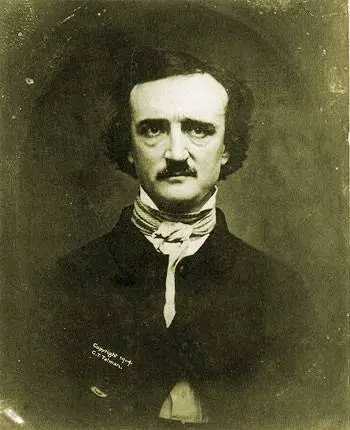

This is a couplet, presumably part of an unfinished poem Poe was writing in 1847.

In January of that year, Poe’s wife Virginia had died in New York of tuberculosis.

It is assumed that the poem was inspired by her death. It is difficult to discern,

however, if Poe had intended the completed poem to be published or if it was personal.

Poe scribbled the couplet onto a manuscript copy of his poem “Eulalie.” That poem

seems autobiographical, referring to his joy upon marriage. The significance of the

couplet implies that he has gone back into a state of loneliness similar to before

his marriage.

Deep in earth my love is lying

And I must weep alone.

A DREAM WITHIN A DREAM

Take this kiss upon the brow!

And, in parting from you now,

Thus much let me avow —

You are not wrong, who deem

That my days have been a dream;

Yet if hope has flown away

In a night, or in a day,

In a vision, or in none,

Is it therefore the less gone?

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.

I stand amid the roar

Of a surf-tormented shore,

And I hold within my hand

Grains of the golden sand —

How few! yet how they creep

Through my fingers to the deep,

While I weep — while I weep!

O God! can I not grasp

Them with a tighter clasp?

O God! can I not save

One from the pitiless wave?

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?

ELDORADO

Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado.

But he grew old —

This knight so bold —

And o’er his heart a shadow

Fell, as he found

No spot of ground

That looked like Eldorado.

And, as his strength

Failed him at length,

He met a pilgrim shadow —

‘Shadow,’ said he,

‘Where can it be —

This land of Eldorado?’

‘Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,’

The shade replied, —

‘If you seek for Eldorado!’

1849.

TO MY MOTHER

Because I feel that, in the Heavens above,

The angels, whispering to one another,

Can find, among their burning terms of love,

None so devotional as that of “Mother,”

Therefore by that dear name I long have called you —

You who are more than mother unto me,

And fill my heart of hearts, where Death installed you

In setting my Virginia’s spirit free.

My mother — my own mother, who died early,

Was but the mother of myself; but you

Are mother to the one I loved so dearly,

And thus are dearer than the mother I knew

By that infinity with which my wife

Was dearer to my soul than its soul-life.

1849.

THE BELLS

I.

HEAR the sledges with the bells —

Silver bells!

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In the icy air of night!

While the stars that oversprinkle

All the heavens, seem to twinkle

With a crystalline delight;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells —

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.

II.

Hear the mellow wedding-bells

Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells!

Through the balmy air of night

How they ring out their delight! —

From the molten-golden notes,

And all in tune,

What a liquid ditty floats

To the turtle-dove that listens, while she gloats

On the moon!

Oh, from out the sounding cells,

What a gush of euphony voluminously wells!

How it swells!

How it dwells

On the Future! — how it tells

Of the rapture that impels

To the swinging and the ringing

Of the bells, bells, bells —

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells —

To the rhyming and the chiming of the bells!

III.

Hear the loud alarum bells —

Brazen bells!

What tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

How they scream out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

They can only shriek, shriek,

Out of tune,

In a clamorous appealing to the mercy of the fire,

In a mad expostulation with the deaf and frantic fire,

Leaping higher, higher, higher,

With a desperate desire,

And a resolute endeavor

Now — now to sit, or never,

By the side of the pale-faced moon.

Oh, the bells, bells, bells!

What a tale their terror tells

Of Despair!

How they clang, and clash, and roar!

What a horror they outpour

On the bosom of the palpitating air!

Yet the ear, it fully knows,

By the twanging

And the clanging,

How the danger ebbs and flows;

Yet, the ear distinctly tells,

In the jangling

And the wrangling,

How the danger sinks and swells,

By the sinking or the swelling in the anger of the bells —

Of the bells —

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells —

In the clamour and the clangour of the bells!

IV.

Hear the tolling of the bells —

Iron bells!

What a world of solemn thought their monody compels!

In the silence of the night,

How we shiver with affright

At the melancholy meaning of their tone!

For every sound that floats

From the rust within their throats

Is a groan.

And the people — ah, the people —

They that dwell up in the steeple,

All alone,

And who, tolling, tolling, tolling,

In that muffled monotone,

Feel a glory in so rolling

On the human heart a stone —

They are neither man nor woman —

They are neither brute nor human —

They are Ghouls: —

And their king it is who tolls: —

And he rolls, rolls, rolls, rolls,

Rolls

A pæan from the bells!

And his merry bosom swells

With the pæan of the bells!

And he dances, and he yells;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the pæan of the bells —

Of the bells: —

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the throbbing of the bells —

Of the bells, bells, bells —

To the sobbing of the bells: —

Keeping time, time, time,

As he knells, knells, knells,

In a happy Runic rhyme,

To the rolling of the bells —

Of the bells, bells, bells: —

To the tolling of the bells —

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells —

To the moaning and the groaning of the bells.

1849.

TO ISADORE

This poem is of doubtful origin

I

BENEATH the vine-clad eaves,

Whose shadows fall before

Thy lowly cottage door

Under the lilac’s tremulous leaves —

Within thy snowy claspeèd hand

The purple flowers it bore..

Last eve in dreams, I saw thee stand,

Like queenly nymphs from Fairy-land —

Enchantress of the flowery wand,

Most beauteous Isadore!

II

And when I bade the dream

Upon thy spirit flee,

Thy violet eyes to me

Upturned, did overflowing seem

With the deep, untold delight

Of Love’s serenity;

Thy classic brow, like lilies white

And pale as the Imperial Night

Upon her throne, with stars bedight,

Enthralled my soul to thee!

III

Ah I ever I behold

Thy dreamy, passionate eyes,

Blue as the languid skies

Hung with the sunset’s fringe of gold;

Now strangely clear thine image grows,

And olden memories

Are startled from their long repose

Like shadows on the silent snows

When suddenly the night-wind blows

Where quiet moonlight ties.

IV

Like music heard in dreams,

Like strains of harps unknown,

Of birds forever flown

Audible as the voice of streams

That murmur in some leafy dell,

I hear thy gentlest tone,

And Silence cometh with her spell

Like that which on my tongue doth dwell,

When tremulous in dreams I tell

My love to thee alone!

V

In every valley heard,

Floating from tree to tree,

Less beautiful to, me,

The music of the radiant bird,

Than artless accents such as thine

Whose echoes never flee!

Ah! how for thy sweet voice I pine: —

For uttered in thy tones benign

(Enchantress!) this rude name of mine

Doth seem a melody!

THE VILLAGE STREET

This poem is of doubtful origin

IN these rapid, restless shadows,

Once I walked at eventide,

When a gentle, silent maiden,

Wal ked in beauty at my side

She alone there walked beside me

All in beauty, like a bride.

Pallidly the moon was shining

On the dewy meadows nigh;

On the silvery, silent rivers,

On the mountains far and high

On the ocean’s star-lit waters,

Where the winds a-weary die.

Slowly, silently we wandered

From the open cottage door,

Underneath the elm’s long branches

To the pavement bending o’er;

Underneath the mossy willow

And the dying sycamore.

With the myriad stars in beauty

All bedight, the heavens were seen,

Radiant hopes were bright around me,

Like the light of stars serene;

Like the mellow midnight splendor

Of the Night’s irradiate queen.

Audibly the elm-leaves whispered

Peaceful, pleasant melodies,

Like the distant murmured music

Of unquiet, lovely seas:

While the winds were hushed in slumber

In the fragrant flowers and trees.

Wondrous and unwonted beauty

Still adorning all did seem,

While I told my love in fables

‘Neath the willows by the stream;

Would the heart have kept unspoken

Love that was its rarest dream!

Instantly away we wandered

In the shadowy twilight tide,

She, the silent, scornful maiden,

Walking calmly at my side,

With a step serene and stately,

All in beauty, all in pride.

Vacantly I walked beside her.

On the earth mine eyes were cast;

Swift and keen there came unto me

Ritter memories of the past

On me, like the rain in Autumn

On the dead leaves, cold and fast.

Underneath the elms we parted,

By the lowly cottage door;

One brief word alone was uttered

Never on our lips before;

And away I walked forlornly,

Broken-hearted evermore.

Slowly, silently I loitered,

Homeward, in the night, alone;

Sudden anguish bound my spirit,

That my youth had never known;

Wild unrest, like that which cometh

When the Night’s first dream hath flown.

Now, to me the elm-leaves whisper

Mad, discordant melodies,

And keen melodies like shadows

Haunt the moaning willow trees,

And the sycamores with laughter

Mock me in the nightly breeze.

Sad and pale the Autumn moonlight

Through the sighing foliage streams;

And each morning, midnight shadow,

Shadow of my sorrow seems;

Strive, O heart, forget thine idol!

And, O soul, forget thy dreams!

THE FOREST REVERIE

This poem is of doubtful origin

‘Tis said that when

The hands of men

Tamed this primeval wood,

And hoary trees with groans of woe,

Like warriors by an unknown foe,

Were in their strength subdued,

The virgin Earth Gave instant birth

To springs that ne’er did flow

That in the sun Did rivulets run,

And all around rare flowers did blow

The wild rose pale Perfumed the gale

And the queenly lily adown the dale

(Whom the sun and the dew

And the winds did woo),

With the gourd and the grape luxuriant grew.

So when in tears

The love of years

Is wasted like the snow,

And the fine fibrils of its life

By the rude wrong of instant strife

Are broken at a blow

Within the heart

Do springs upstart

Of which it doth now know,

And strange, sweet dreams,

Like silent streams

That from new fountains overflow,

With the earlier tide

Of rivers glide

Deep in the heart whose hope has died —

Quenching the fires its ashes hide, —

Its ashes, whence will spring and grow

Sweet flowers, ere long,

The rare and radiant flowers of song!

ANNABEL LEE

This is the last complete poem that was composed by Poe. Like many of his previous

poems, it explores the theme of the death of a beautiful woman. The narrator, who

had fallen in love with Annabel Lee when they were young, has a love for her so strong

that even angels are jealous. He retains his love for her even after her death. There

has been debate over who, if anyone, was the inspiration for Annabel Lee. Though many women have been suggested, Poe’s wife Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe is one

of the more credible candidates. Written in 1849, it was not published until shortly

after Poe’s death that same year.

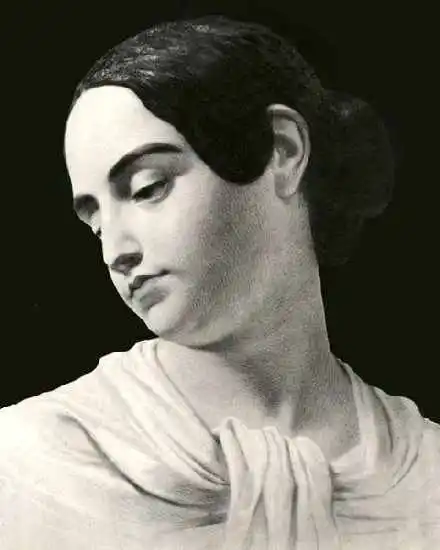

Poe’s wife Virginia is often assumed to be the inspiration for “Annabel Lee”.

ANNABEL LEE

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden lived whom you may know

By the name of ANNABEL LEE; —

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and She was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love —

I and my ANNABEL LEE —

With a love that the wingéd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud by night

Chilling my ANNABEL LEE;

So that her high-born kinsmen came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up, in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in Heaven,

Went envying her and me;

Yes! that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud, chilling

And killing my ANNABEL LEE.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we —

Of many far wiser than we —

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful ANNABEL LEE: —

For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful ANNABEL LEE;

And the stars never rise but I see the bright eyes

Of the beautiful ANNABEL LEE;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling, my darling, my life and my bride

In her sepulchre there by the sea —

In her tomb by the side of the sea.

1849.

The Tales

The 2012 film inspired by Poe’s works

John Cusack playing the part of the famous author

THE COMPLETE TALES IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

METZENGERSTEIN

THE DUC DE L’OMELETTE

A TALE OF JERUSALEM

LOSS OF BREATH

BON-BON

MS. FOUND IN A BOTTLE

THE ASSIGNATION

BERENICE (ORIGINAL)

BERENICE (REVISED)

MORELLA

LIONIZING.

THE UNPARALLELED ADVENTURE OF ONE HANS PFAALL

KING PEST

SHADOW

FOUR BEASTS IN ONE

MYSTIFICATION

SILENCE

LIGEIA

HOW TO WRITE A BLACKWOOD ARTICLE

A PREDICAMENT

THE DEVIL IN THE BELFRY

THE MAN THAT WAS USED UP

THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER

WILLIAM WILSON

THE CONVERSATION OF EIROS AND CHARMION

WHY THE LITTLE FRENCHMAN WEARS HIS HAND IN A SLING

THE BUSINESS MAN

THE MAN IN THE CROWD

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

A DESCENT INTO THE MAELSTRÖM

THE ISLAND OF THE FAY

THE COLLOQUY OF MONOS AND UNA.

NEVER BET THE DEVIL YOUR HEAD

ELEONORA

THREE SUNDAYS IN A WEEK

THE OVAL PORTRAIT

THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH

THE LANDSCAPE GARDEN

THE MYSTERY OF MARIE ROGÊT

THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM

THE TELL-TALE HEART

THE GOLD-BUG

THE BLACK CAT (1843 Version)

THE BLACK CAT (1845 Version)

DIDDLING CONSIDERED AS ONE OF THE EXACT SCIENCES

THE SPECTACLES

A TALE OF THE RAGGED MOUNTAINS

THE PREMATURE BURIAL

MESMERIC REVELATION

THE OBLONG BOX

THE ANGEL OF THE ODD

THOU ART THE MAN

THE LITERARY LIFE OF THINGUM BOB, ESQ.

THE PURLOINED LETTER

THE THOUSAND-AND-SECOND TALE OF SCHEHERAZADE

SOME WORDS WITH A MUMMY

THE POWER OF WORDS

THE IMP OF THE PERVERSE

THE SYSTEM OF DOCTOR TARR AND PROFESSOR FETHER

THE FACTS IN THE CASE OF M. VALDEMAR

THE SPHINX

THE CASK OF AMONTILLADO

THE DOMAIN OF ARNHEIM

MELLONTA TAUTA

HOP-FROG

VON KEMPELEN AND HIS DISCOVERY

X-ING A PARAGRAB

LANDOR’S COTTAGE

THE LIGHTHOUSE

THE COMPLETE TALES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER

A DESCENT INTO THE MAELSTRÖM

A PREDICAMENT

A TALE OF JERUSALEM

A TALE OF THE RAGGED MOUNTAINS

BERENICE (ORIGINAL)

BERENICE (REVISED)

BON-BON

DIDDLING CONSIDERED AS ONE OF THE EXACT SCIENCES

ELEONORA

FOUR BEASTS IN ONE

HOP-FROG

HOW TO WRITE A BLACKWOOD ARTICLE

KING PEST

LANDOR’S COTTAGE

LIGEIA

LIONIZING.

LOSS OF BREATH

MELLONTA TAUTA

MESMERIC REVELATION

METZENGERSTEIN

MORELLA

MS. FOUND IN A BOTTLE

MYSTIFICATION

NEVER BET THE DEVIL YOUR HEAD

SHADOW

SILENCE

SOME WORDS WITH A MUMMY

THE ANGEL OF THE ODD

THE ASSIGNATION

THE BLACK CAT (1843 Version)

THE BLACK CAT (1845 Version)

THE BUSINESS MAN

THE CASK OF AMONTILLADO

THE COLLOQUY OF MONOS AND UNA.

THE CONVERSATION OF EIROS AND CHARMION

THE DEVIL IN THE BELFRY

THE DOMAIN OF ARNHEIM

THE DUC DE L’OMELETTE

THE FACTS IN THE CASE OF M. VALDEMAR

THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER

THE GOLD-BUG

THE IMP OF THE PERVERSE

THE ISLAND OF THE FAY

THE LANDSCAPE GARDEN

THE LIGHTHOUSE

THE LITERARY LIFE OF THINGUM BOB, ESQ.

THE MAN IN THE CROWD

THE MAN THAT WAS USED UP

THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

THE MYSTERY OF MARIE ROGÊT

THE OBLONG BOX

THE OVAL PORTRAIT

THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM

THE POWER OF WORDS

THE PREMATURE BURIAL

THE PURLOINED LETTER

THE SPECTACLES

THE SPHINX

THE SYSTEM OF DOCTOR TARR AND PROFESSOR FETHER

THE TELL-TALE HEART

THE THOUSAND-AND-SECOND TALE OF SCHEHERAZADE

THE UNPARALLELED ADVENTURE OF ONE HANS PFAALL

THOU ART THE MAN

THREE SUNDAYS IN A WEEK

VON KEMPELEN AND HIS DISCOVERY

WHY THE LITTLE FRENCHMAN WEARS HIS HAND IN A SLING

WILLIAM WILSON

X-ING A PARAGRAB

METZENGERSTEIN

A Tale In Imitation of the German

This is Poe’s first short story, which was published in the pages of Philadelphia’s Saturday Courier magazine, in 1832. The story follows the young Frederick, the last of the Metzengerstein

family who carries on a long-standing feud with the Berlifitzing family. Suspected

of causing a fire that kills the Berlifitzing family patriarch, Frederick becomes

intrigued with a previously-unnoticed and untamed horse. Metzengerstein is punished

for his cruelty when his own home catches fire and the horse carries him into the

flame.

METZENGERSTEIN

Horror and fatality have been stalking abroad in all ages. Why then give a date to

this story I have to tell? Let it suffice to say, that at the period of which I speak,

there existed, in the interior of Hungary, a settled although hidden belief in the

doctrines of the Metempsychosis. Of the doctrines themselves — that is, of their falsity,

or of their probability — I say nothing. I assert, however, that much of our incredulity

— as La Bruyere says of all our unhappiness —“vient de ne pouvoir etre seuls.”

But there are some points in the Hungarian superstition which were fast verging to

absurdity. They — the Hungarians — differed very essentially from their Eastern authorities.

For example, “The soul,” said the former — I give the words of an acute and intelligent

Parisian —“ne demeure qu’un seul fois dans un corps sensible: au reste — un cheval,

un chien, un homme meme, n’est que la ressemblance peu tangible de ces animaux.”

The families of Berlifitzing and Metzengerstein had been at variance for centuries.

Never before were two houses so illustrious, mutually embittered by hostility so deadly.

Indeed at the era of this history, it was observed by an old crone of haggard and

sinister appearance, that “fire and water might sooner mingle than a Berlifitzing

clasp the hand of a Metzengerstein.” The origin of this enmity seems to be found in

the words of an ancient prophecy —“A lofty name shall have a fearful fall when, as

the rider over his horse, the mortality of Metzengerstein shall triumph over the immortality

of Berlifitzing.”

To be sure the words themselves had little or no meaning. But more trivial causes

have given rise — and that no long while ago — to consequences equally eventful. Besides,

the estates, which were contiguous, had long exercised a rival influence in the affairs

of a busy government. Moreover, near neighbors are seldom friends; and the inhabitants

of the Castle Berlifitzing might look, from their lofty buttresses, into the very

windows of the palace Metzengerstein. Least of all had the more than feudal magnificence,

thus discovered, a tendency to allay the irritable feelings of the less ancient and

less wealthy Berlifitzings. What wonder then, that the words, however silly, of that

prediction, should have succeeded in setting and keeping at variance two families

already predisposed to quarrel by every instigation of hereditary jealousy? The prophecy

seemed to imply — if it implied anything — a final triumph on the part of the already

more powerful house; and was of course remembered with the more bitter animosity by

the weaker and less influential.

Wilhelm, Count Berlifitzing, although loftily descended, was, at the epoch of this

narrative, an infirm and doting old man, remarkable for nothing but an inordinate

and inveterate personal antipathy to the family of his rival, and so passionate a

love of horses, and of hunting, that neither bodily infirmity, great age, nor mental

incapacity, prevented his daily participation in the dangers of the chase.

Frederick, Baron Metzengerstein, was, on the other hand, not yet of age. His father,

the Minister G—, died young. His mother, the Lady Mary, followed him quickly after.

Frederick was, at that time, in his fifteenth year. In a city, fifteen years are no

long period — a child may be still a child in his third lustrum: but in a wilderness

— in so magnificent a wilderness as that old principality, fifteen years have a far

deeper meaning.

The beautiful Lady Mary! How could she die?— and of consumption! But it is a path

I have prayed to follow. I would wish all I love to perish of that gentle disease.

How glorious — to depart in the heyday of the young blood — the heart of all passion

— the imagination all fire — amid the remembrances of happier days — in the fall of

the year — and so be buried up forever in the gorgeous autumnal leaves!

Thus died the Lady Mary. The young Baron Frederick stood without a living relative

by the coffin of his dead mother. He placed his hand upon her placid forehead.

1 comment