Simpson’s James Hogg: A Critical Study (1962) and James Hogg by D. Gifford (1976). There is a concise account of the novel in Walter Allen’s The English Novel (1954), where it is described as ‘an astonishing self-exposure of religious aberration and delusion … a psychological document compared with which Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a crude morality’.

As to additional, concomitant surveys: the best account of witchcraft and its many ramifications is Sir Keith Thomas’s Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971); the atmospherics of Romanticism are to be found in The Portable Coleridge, edited by I. A. Richards (1950, copyright renewed 1978), and in entries by Addison, Lamb, Hazlitt, De Quincey and Leigh Hunt in A Book of English Essays, edited by W. E. Williams (1942); the points raised in the foregoing preface of Hamlet’s relationship with Robert Wringhim Colwan may be checked against essays and remarks on Shakespeare’s play by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers collected in Hamlet: A Casebook, edited by John Jump (1968). Ideas about Edmund Kean and profiles of similar personalities may be found in On Actors and the Art of Acting by George Henry Lewes (1875, reprinted in recent times by the Grove Press, New York). A discussion of the overlaps between acting and madness is also to be located in the present editor’s Stage People (1989). Alexander Mackendrick and Ealing films are dealt with extensively by Philip Kemp in his Lethal Innocence: The Cinema of Alexander Mackendrick (1991). Anthony Burgess’s autobiography comprises two volumes, Little Wilson and Big God (1987) and You’ve Had Your Time (1990).

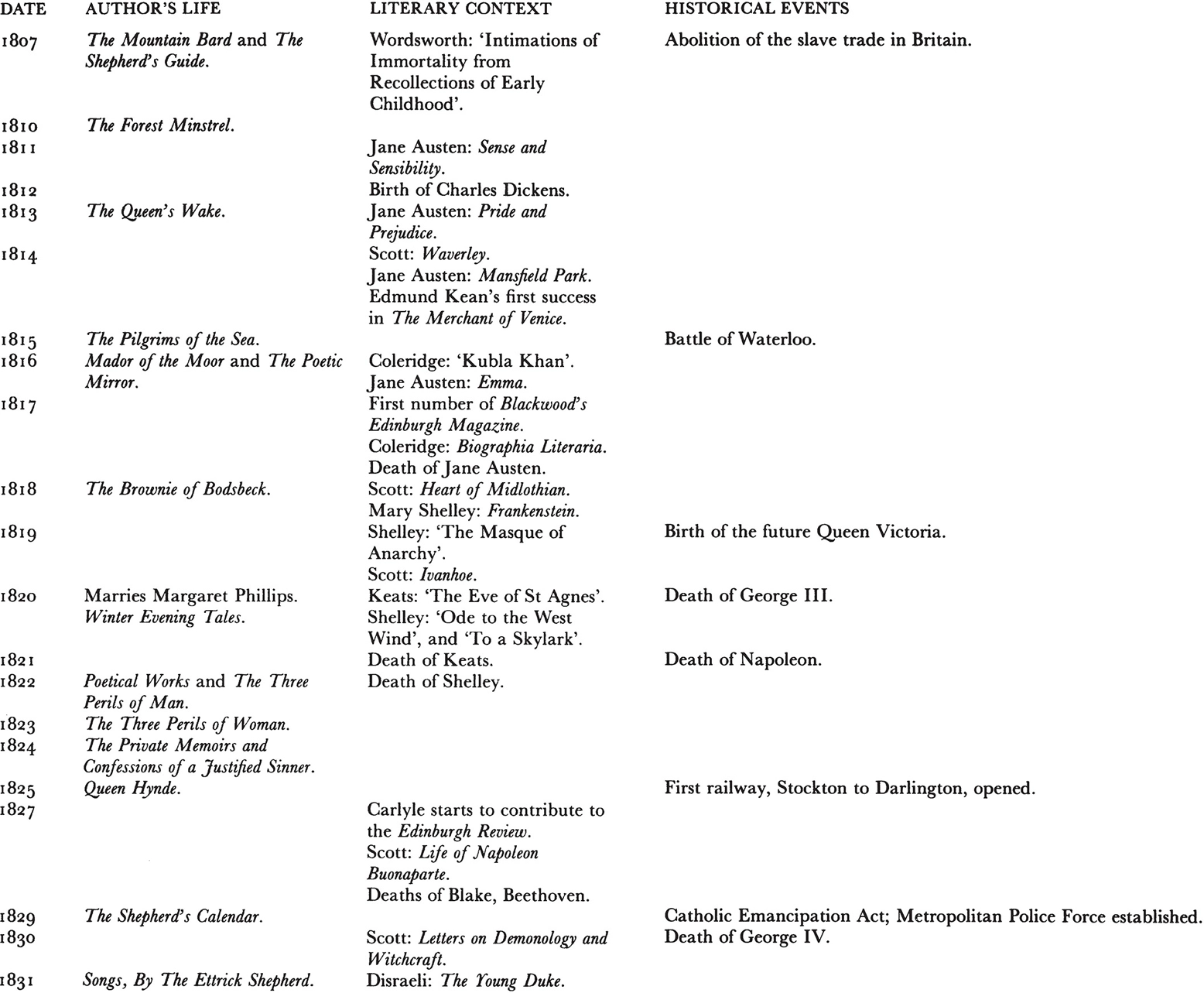

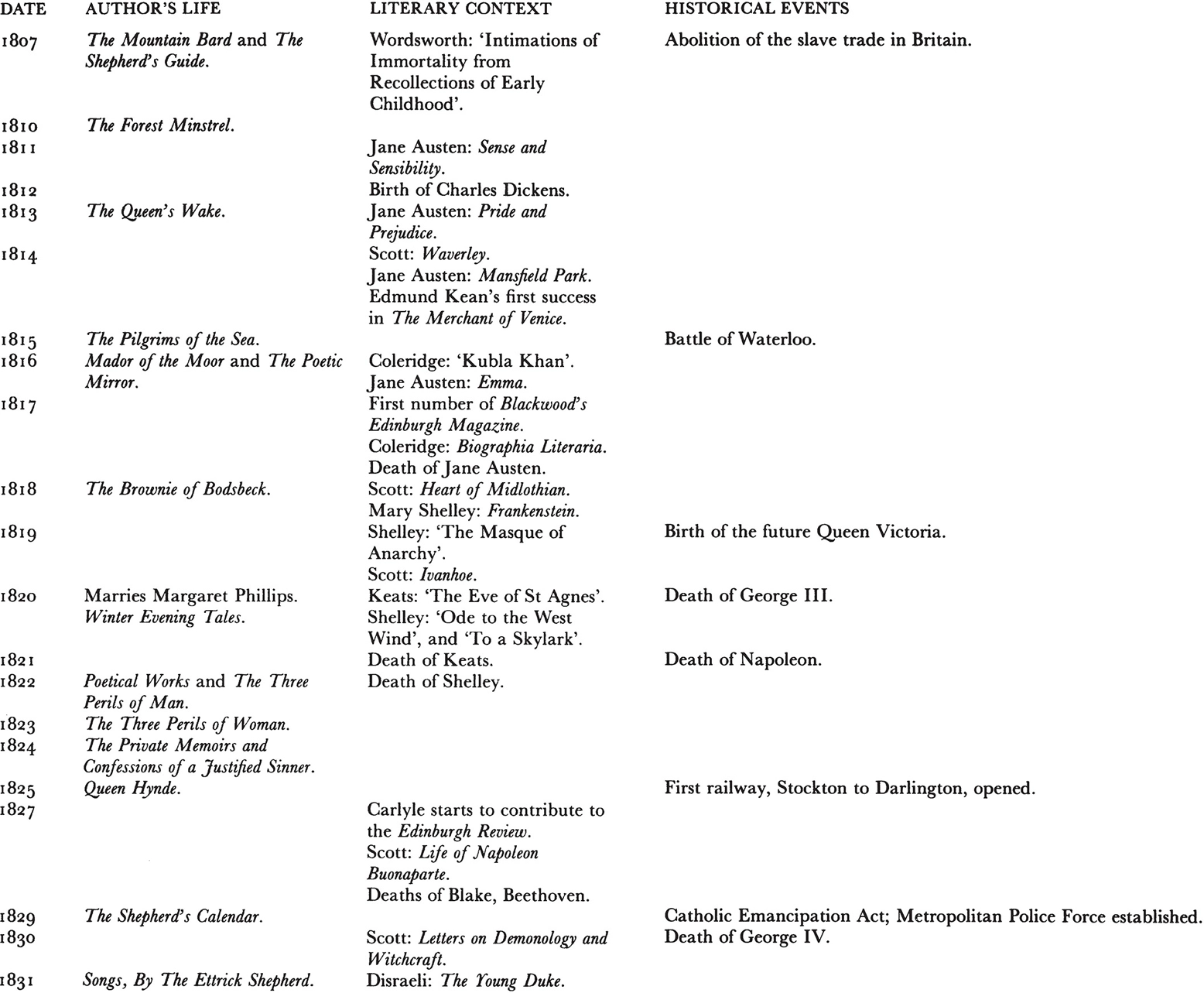

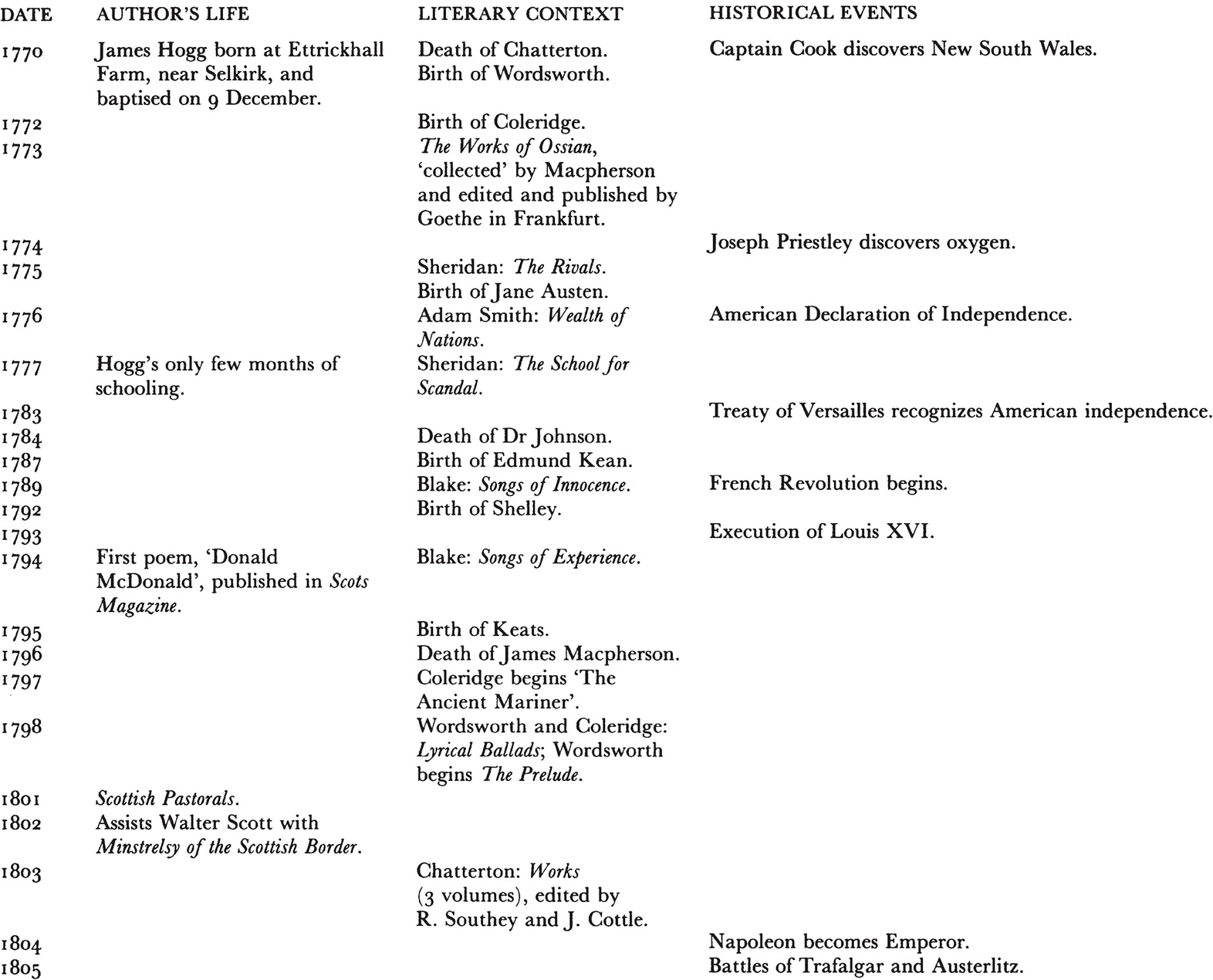

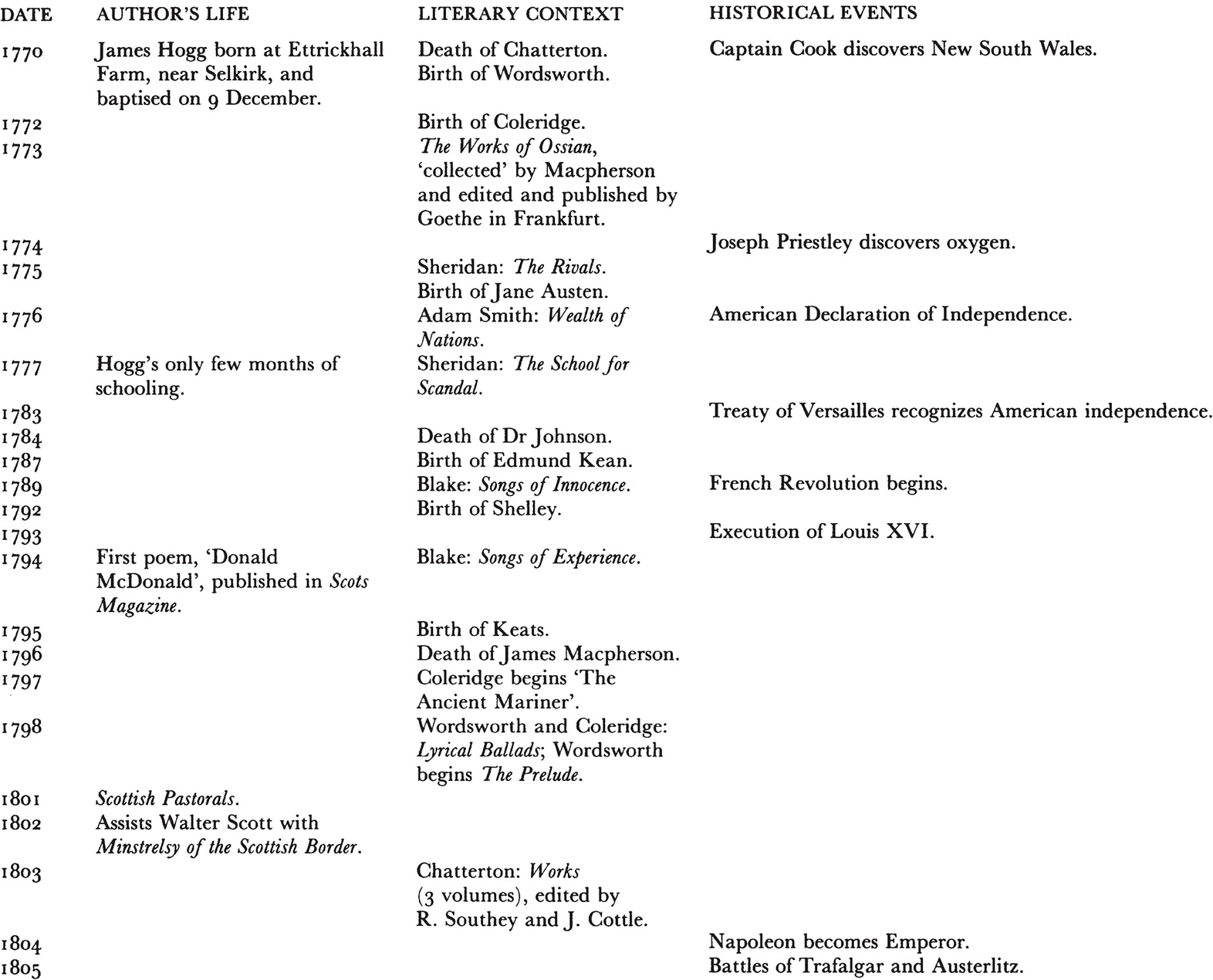

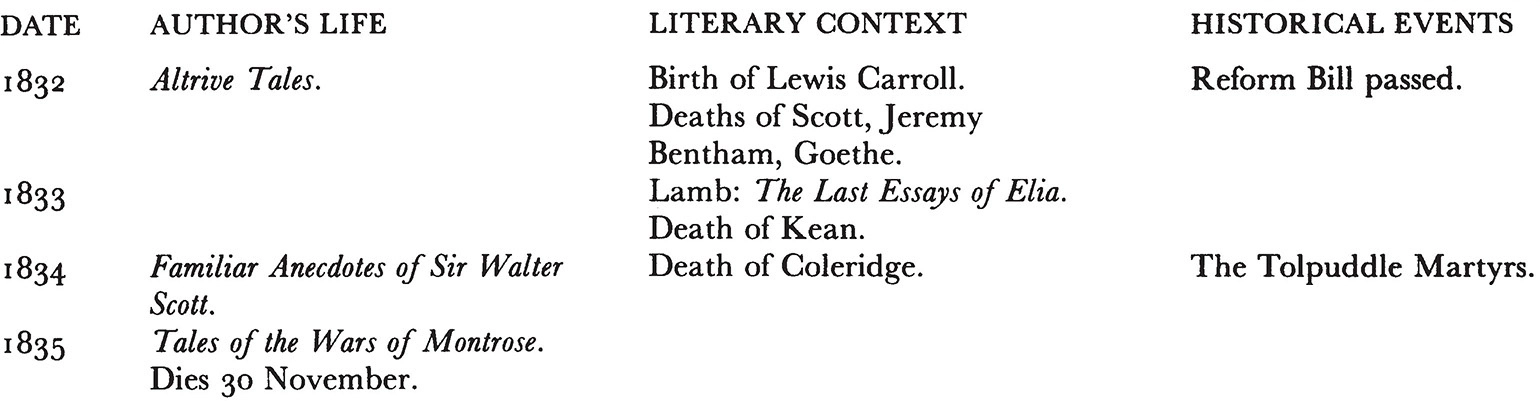

CHRONOLOGY

Please note: Text is repeated below at a larger size.

| DATE |

AUTHOR’S LIFE |

| 1770 |

James Hogg born at Ettrickhall Farm, near Selkirk, and baptised on 9 December. |

| 1777 |

Hogg’s only few months of schooling. |

| 1794 |

First poem, ‘Donald McDonald’, published in Scots Magazine. |

| 1801 |

Scottish Pastorals. |

| 1802 |

Assists Walter Scott with Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. |

| 1807 |

The Mountain Bard and The Shepherd’s Guide. |

| 1810 |

The Forest Minstrel. |

| 1813 |

The Queen’s Wake. |

| 1815 |

The Pilgrims of the Sea. |

| 1816 |

Mador of the Moor and The Poetic Mirror. |

| 1818 |

The Brownie of Bodsbeck. |

| 1820 |

Marries Margaret Phillips.

Winter Evening Tales. |

| 1822 |

Poetical Works and The Three Perils of Man. |

| 1823 |

The Three Perils of Woman. |

| 1824 |

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. |

| 1825 |

Queen Hynde. |

| 1829 |

The Shepherd’s Calendar. |

| 1831 |

Songs, By The Ettrick Shepherd. |

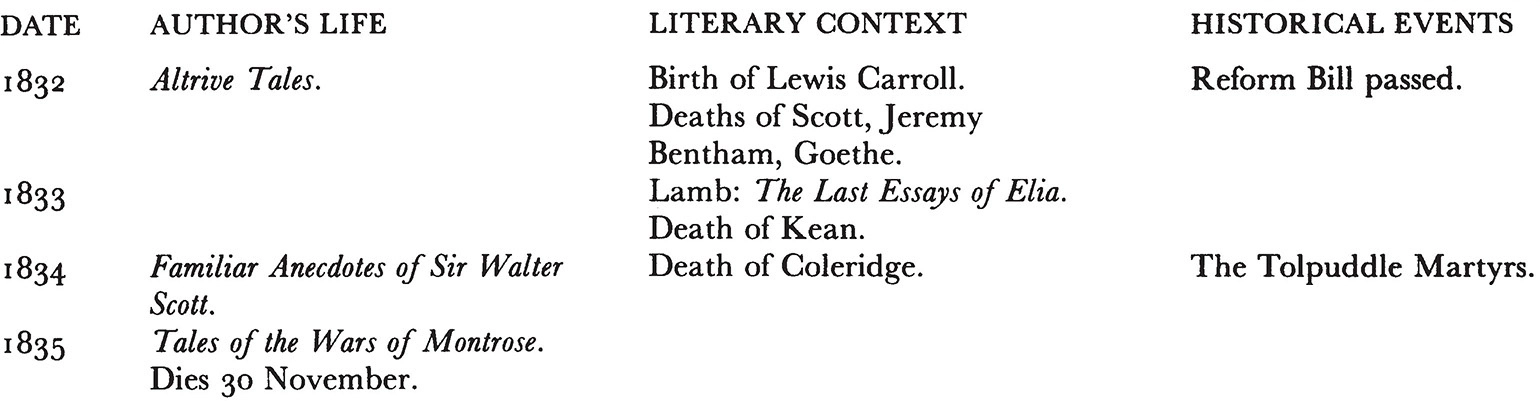

| 1832 |

Altrive Tales. |

| 1834 |

Familiar Anecdotes of Sir Walter Scott. |

| 1835 |

Tales of the Wars of Montrose.

Dies 30 November. |

| DATE |

LITERARY CONTEXT |

| 1770 |

Death of Chatterton.

Birth of Wordsworth. |

| 1772 |

Birth of Coleridge. |

| 1773 |

The Works of Ossian, ‘collected’ by Macpherson and edited and published by Goethe in Frankfurt. |

| 1775 |

Sheridan: The Rivals.

Birth of Jane Austen. |

| 1776 |

Adam Smith: Wealth of Nations. |

| 1777 |

Sheridan: The School for Scandal. |

| 1784 |

Death of Dr Johnson. |

| 1787 |

Birth of Edmund Kean. |

| 1789 |

Blake: Songs of Innocence. |

| 1792 |

Birth of Shelley. |

| 1794 |

Blake: Songs of Experience. |

| 1795 |

Birth of Keats. |

| 1796 |

Death of James Macpherson. |

| 1797 |

Coleridge begins ‘The Ancient Mariner‘. |

| 1798 |

Wordsworth and Coleridge: Lyrical Ballads; Wordsworth begins The Prelude. |

| 1803 |

Chatterton: Works (3 volumes), edited by R. Southey and J. Cottle. |

| 1807 |

Wordsworth: ‘Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood’. |

| 1811 |

Jane Austen: Sense and Sensibility. |

| 1812 |

Birth of Charles Dickens. |

| 1813 |

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice. |

| 1814 |

Scott: Waverley.

Jane Austen: Mansfield Park.

Edmund Kean’s first success in The Merchant of Venice. |

| 1816 |

Coleridge: ‘Kubla Khan’.

Jane Austen: Emma. |

| 1817 |

First number of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.

Coleridge: Biographia Literaria.

Death of Jane Austen. |

| 1818 |

Scott: Heart of Midlothian.

Mary Shelley: Frankenstein. |

| 1819 |

Shelley: ‘The Masque of Anarchy’.

Scott: Ivanhoe. |

| 1820 |

Keats: ‘The Eve of St Agnes’.

Shelley: ‘Ode to the West Wind’, and ‘To a Skylark’. |

| 1821 |

Death of Keats. |

| 1822 |

Death of Shelley. |

| 1827 |

Carlyle starts to contribute to the Edinburgh Review.

Scott: Life of Napoleon Buonaparte.

Deaths of Blake, Beethoven. |

| 1830 |

Scott: Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. |

| 1831 |

Disraeli: The Young Duke |

| 1832 |

Birth of Lewis Carroll.

Deaths of Scott, Jeremy

Bentham, Goethe. |

| 1833 |

Lamb: The Last Essays of Elia.

Death of Kean. |

| 1834 |

Death of Coleridge. |

| DATE |

HISTORICAL EVENTS |

| 1770 |

Captain Cook discovers New South Wales. |

| 1774 |

Joseph Priestley discovers oxygen. |

| 1776 |

American Declaration of Independence. |

| 1783 |

Treaty of Versailles recognizes American independence. |

| 1789 |

French Revolution begins. |

| 1793 |

Execution of Louis XVI. |

| 1804 |

Napoleon becomes Emperor. |

| 1805 |

Battles of Trafalgar and Austerlitz. |

| 1807 |

Abolition of the slave trade in Britain. |

| 1815 |

Battle of Waterloo. |

| 1819 |

Birth of the future Queen Victoria. |

| 1820 |

Death of George III. |

| 1821 |

Death of Napoleon. |

| 1825 |

First railway, Stockton to Darlington, opened. |

| 1829 |

Catholic Emancipation Act; Metropolitan Police Force established. |

| 1830 |

Death of George IV. |

| 1832 |

Reform Bill passed. |

| 1834 |

The Tolpuddle Martyrs. |

The Private Memoirs

and Confessions of

a Justified Sinner:

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF:

With a detail of

curious traditionary facts,

and other evidence,

by the Editor.

THE EDITOR’S NARRATIVE

IT APPEARS from tradition, as well as some parish registers still extant, that the lands of Dalcastle (or Dalchastel, as it is often spelled) were possessed by a family of the name of Colwan, about one hundred and fifty years ago, and for at least a century previous to that period. That family was supposed to have been a branch of the ancient family of Colquhoun, and it is certain that from it spring the Cowans that spread towards the Border. I find that, in the year 1687, George Colwan succeeded his uncle of the same name, in the lands of Dalchastel and Balgrennan; and, this being all I can gather of the family from history, to tradition I must appeal for the remainder of the motley adventures of that house. But, of the matter furnished by the latter of these powerful monitors, I have no reason to complain: It has been handed down to the world in unlimited abundance; and I am certain that, in recording the hideous events which follow, I am only relating to the greater part of the inhabitants of at least four counties of Scotland matters of which they were before perfectly well informed.

This George was a rich man, or supposed to be so, and was married, when considerably advanced in life, to the sole heiress and reputed daughter of a Baillie Orde, of Glasgow. This proved a conjuction anything but agreeable to the parties contracting. It is well known that the Reformation principles had long before that time taken a powerful hold of the hearts and affections of the people of Scotland, although the feeling was by no means general, or in equal degrees; and it so happened that this married couple felt completely at variance on the subject. Granting it to have been so, one would have thought that the laird, owing to his retired situation, would have been the one that inclined to the stern doctrines of the reformers; and that the young and gay dame from the city would have adhered to the free principles cherished by the court party, and indulged in rather to extremity, in opposition to their severe and carping contemporaries.

The contrary, however, happened to be the case. The laird was what his country neighbours called ‘a droll, careless chap’, with a very limited proportion of the fear of God in his heart, and very nearly as little of the fear of man. The laird had not intentionally wronged or offended either of the parties, and perceived not the necessity of deprecating their vengeance. He had hitherto believed that he was living in most cordial terms with the greater part of the inhabitants of the earth, and with the powers above in particular: but woe be unto him if he was not soon convinced of the fallacy of such damning security! for his lady was the most severe and gloomy of all bigots to the principles of the Reformation. Hers were not the tenets of the great reformers, but theirs mightily overstrained and deformed. Theirs was an unguent hard to be swallowed; but hers was that unguent embittered and overheated until nature could not longer bear it. She had imbibed her ideas from the doctrines of one flaming predestinarian divine alone; and these were so rigid that they became a stumbling block to many of his brethren, and a mighty handle for the enemies of his party to turn the machine of the state against them.

The wedding festivities at Dalcastle partook of all the gaiety, not of that stern age, but of one previous to it. There was feasting, dancing, piping, and singing: the liquors were handed around in great fulness, the ale in large wooden bickers, and the brandy in capacious horns of oxen. The laird gave full scope to his homely glee. He danced — he snapped his fingers to the music — clapped his hands and shouted at the turn of the tune. He saluted every girl in the hall whose appearance was anything tolerable, and requested of their sweethearts to take the same freedom with his bride, by way of retaliation. But there she sat at the head of the hall in still and blooming beauty, absolutely refusing to tread a single measure with any gentleman there.

1 comment