In this process an important role is played by custom, ritual and taboo, and I came to possess a fair amount of information in this regard…In our home there were other dependents, boys mainly, and at an early age I drifted away from my parents and moved about, played and ate together with other boys. In fact I hardly remember any occasion when I was ever alone at home. There were always other children with whom I shared food and blankets at night. I must have been about five years old when I began going out with other boys to look after sheep and calves and when I was introduced to the exciting love of the veld. Later when I was a bit older I was able to look after cattle as well…[A] game I enjoyed very much was what I call Khetha (choose-the-one-you-like)…We would stop girls of our age group along the way and ask each one to choose the boy she loved. It was a rule that the girl’s choice would be respected and, once she had selected her favourite, she was free to continue her journey escorted by the boy she had chosen. Nimble-witted girls used to combine and all choose one boy, usually the ugliest or dullest, and thereafter tease or bully him along the way…Finally, we used to sing and dance and fully enjoyed the perfect freedom we seemed to have far away from the old people. After supper we would listen enthralled to my mother and sometimes my aunt telling us stories, legends, myths and fables which have come down from countless generations, and all of which tended to stimulate the imagination and contained some valuable moral lesson. As I look back to those days I am inclined to believe that the type of life I led at my home, my experiences in the veld where we worked and played together in groups, introduced me at an early age to the ideas of collective effort. The little progress I made in this regard was later undermined by the type of formal education I received which tended to stress individual more than collective values. Nevertheless, in the mid 1940s when I was drawn into the political struggle, I could adjust myself to discipline without difficulty, perhaps because of my early upbringing.

6. FROM HIS UNPUBLISHED AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL MANUSCRIPT WRITTEN IN PRISON

The regent was not keen that I visit Qunu, lest I should fall into bad company and run away from school, so he reasoned. He would allow me only a few days to go home. On other occasions he would arrange for my mother to be fetched so that she could see me at the royal residence. It was always an exciting moment for me to visit Qunu and see my mother and sisters and other members of the family. I was particularly happy in the company of my cousin, Alexander Mandela, who inspired and encouraged me on questions of education in those early days. He and my niece, Phathiwe Rhanugu (she was much older than me), were perhaps the first members of our clan to qualify as teachers. Were it not for their advice and patient persuasion I doubt if I would have succeeded in resisting the attractions offered by the easy life outside the classroom. The two influences that dominated my thoughts and actions during those days were chieftaincy and the church. After all, the only heroes I had heard of at that time had almost all been chiefs, and the respect enjoyed by the regent from both black and white tended to exaggerate the importance of this institution in my mind. I saw chieftaincy not only as the pivot around which community life turned, but as the key to positions of influence, power and status. Equally important was the position of the church, which I associated not so much with the body and doctrine contained in the Bible but with the person of Reverend Matyolo. In this circuit he was as popular as the regent, and the fact that in spiritual matters he was the regent’s superior and leader, stressed the enormous power of the church. What was even more was that all the progress my people had made – the schools that I attended, the teachers who taught me, the clerks and interpreters in government offices, the agricultural demonstrators and policemen – were all the products of missionary schools. Later the dual position of the chiefs as representatives of their people and as government servants compelled me to assess their position more realistically, and not merely from the point of view of my own family background or of the exceptional chiefs who identified themselves with the struggle of their people. As descendants of the famous heroes that led us so well during the wars of dispossession and as the traditional leaders in their own right, chiefs are entitled to be treated with respect. But as agents of an oppressive government that is regarded as the enemy of the black man, the same chiefs are the objects of criticism and hostility. The institution of chieftaincy itself has been captured by the government and must now be seen as part of the machinery of oppression. My experiences also enable me to formulate a more balanced assessment of the role of the missionaries and to realise the folly of judging the issue simply in terms of relations with individual priests. Nevertheless, I have always considered it dangerous to underestimate the influence of both institutions amongst the people, and for this reason I have repeatedly urged caution in dealing with them.

.....................................................................................

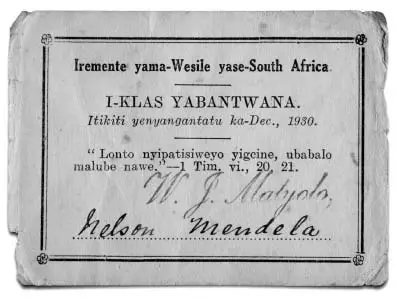

Mandela’s Methodist Church card, 1930.

7.

1 comment