Dostoevsky combines the French theme of the young man from the provinces with Balzac’s (and others’) portrait of the struggle of conscience in a world of waning faith in order to render Raskolnikov’s oscillations between Napoleonic ambition and selfless compassion. Dostoevsky casts the police investigator Porfiry as Raskolnikov’s spiritual guide, following the model of French detective fiction, and disguises a religious allegory as a suspense tale inspired by the French feuilleton novels.

Dostoevsky’s tale of murder is a parable for his time, designed to turn his contemporaries away from a false view of the nature of man that was already dominant in the West, one he feared would become predominant in Russia at a point in history when he saw the intellect being enshrined at the expense of the human spirit. In Crime and Punishment Dostoevsky uses newspaper articles, French popular novels, and masterpieces of French realism—as well as Russian prose from Pushkin’s “Queen of Spades” (1834) to Chernyshevsky’s polemical novel—to create a vivid psychological drama. Dostoevsky gives us the painful experience of entering Raskolnikov’s world and psyche in order to show us the horrific consequences of the materialist worldview, already prevailing in the West, that he feared was coming to dominate Russian social thought. He grounds his rejection of socialism, utilitarianism, and enlightened self-interest in a religious understanding of human nature, whose compassion and self-sacrifice has its perfect model in Jesus Christ. By bringing readers along Raskolnikov’s tortured path, Dostoevsky prepares us to accept John’s message and to view the world of St. Petersburg that we have experienced at close range and in vivid realistic detail from a new, and higher, perspective.

Priscilla Meyer received her B.A. from the University of California at Berkeley and her Ph.D. from Princeton University. A professor of Russian language and literature at Wesleyan University, she teaches courses on nineteenth- and twentieth-century prose, the double in literature, and the French and Russian novel, and conducts seminars on Nabokov and Gogol. She has written about and translated the work of the 1960s generation of Soviet writers, including Vasily Ak senov, Yuz Aleshkovsky, and Andrei Bitov; she edited the first collection of Bitov’s stories to be translated into English: Life in Windy Weather. She wrote Find What the Sailor Has Hidden, the first monograph on Nabokov’s Pale Fire, and has recently completed a book on French sources of the nineteenth-century Russian novel, How the Russians Read the French. She is co-editor of four essay collections: Dostoevsky and Gogol: Texts and Criticism, Essays on Gogol: Logos and the Russian Word, Nabokov’s World, and Yuz! Essays in Honor of the 75th Birthday of Yuz Aleshkovsky. She has published articles in scholarly journals in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia on Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Tolstoy, and Nabokov, and on twentieth-century prose.

LIST OF CHARACTERS

Russian middle names, called “patronymics,” are derived from the father’s first name, with a suffix that indicates the gender of the child. Russian speakers use the first name and patronymic together—for example, Rodion Romanovich—when they want to refer to someone in a formal way. Family members and close friends use diminutives, shortened versions of the first name—for example, Rodia—to refer to one another affectionately. In this list, diminutives and nicknames appear in parentheses after the full names.

RODION ROMANOVICH RASKOLNIKOV (RODIA): The protagonist.

PULCHERIA ALEXANDROVNA RASKOLNIKOV: Raskolnikov’s mother.

AVDOTIA ROMANOVNA RASKOLNIKOV (DUNIA): Raskolnikov’s sister.

DMITRI PROKOFICH RAZUMIKHIN: Raskolnikov’s friend; a poor ex-student.

ALIONA IVANOVNA: The pawnbroker Raskolnikov kills; often referred to as the “old woman.”

LIZAVETA IVANOVNA: The half-sister of Aliona Ivanovna; a friend of Sonia.

SEMION ZAHAROVICH MARMELADOV: A government official who is an alcoholic.

KATERINA IVANOVNA MARMELADOV: The wife of Marmeladov; she is afflicted with consumption.

SOFIA SEMIONOVNA MARMELADOV (SONIA): Raskolnikov’s beloved; daughter of the Marmeladovs.

POLENKA MARMELADOV (POLIA): The eldest daughter of Katerina Ivanovna from a previous marriage.

LIDA MARMELADOV: The daughter of Katerina Ivanovna from a previous marriage.

KOLIA MARMELADOV: The son of Katerina Ivanovna from a previous marriage.

AMALIA FIODOROVNA LIPPEWECHSEL: The landlady of the Marmeladovs. Her surname is German, but she refers to herself by the Russian-sounding Amalia Ivanovna; to irritate her, Katerina Ivanovna calls her Amalia Ludwigovna, which calls attention to her German origin.

ARKADY IVANOVICH SVIDRIGAILOV: Dunia’s former employer.

MARFA PETROVNA SVIDRIGAILOV: The wife of Svidrigailov.

PETER PETROVICH LUZHIN: Dunia’s fiancé; a distant relative of Marfa Svidrigailov.

ANDREI SEMIONOVICH LEBEZIATNIKOV: Luzhin’s roommate.

ZOSSIMOV: Raskolnikov’s doctor; a friend of Dmitri Razumikhin.

NASTASIA PETROVNA: A servant in the house where Raskolnikov lives; she tends to him after the murders.

PRASKOVIA PAVLOVNA ZARNITSYN: Raskolnikov’s landlady; Raskolnikov had been engaged to her daughter, who died.

KOCH: With Pestriakov, he discovers the murders.

PESTRIAKOV: With Koch, he discoverers the murders.

PORFIRY PETROVICH: The official investigating the murders.

ILIA PETROVICH: A police official.

NIKODIM FOMICH: The chief of police.

NIKOLAI DEMENTIEV (MIKOLKA): A painter accused of the murders.

AFANASY IVANOVICH VAKHRUSHIN: A merchant; Raskolnikov’s mother borrows money from him to send to her son.

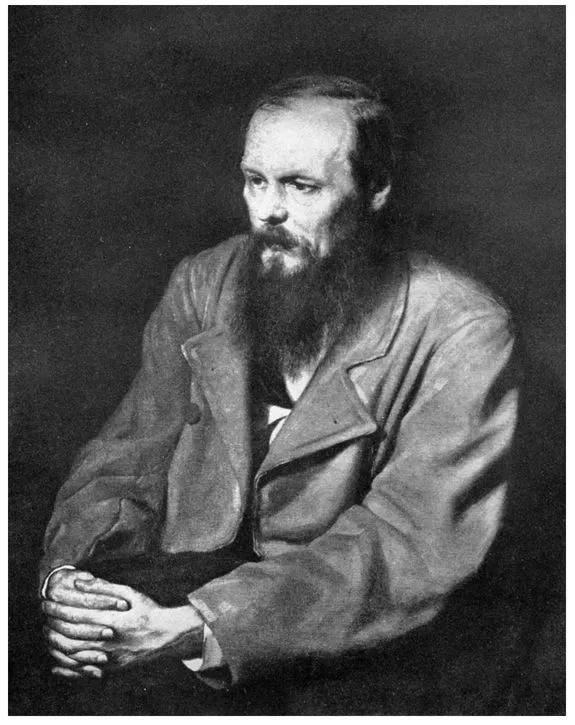

F. M. Dostoevsky. Portrait by V. Perov. 1872

RASKOLNIKOV’S PETERSBURG

1. Raskolnikov’s room

2. The pawnbroker’s room

3. Sonya’s room

4. Haymarket Square

5. Place of Svidrigaylov’s suicide

6. Tuchkov Bridge

7. Yusupov Gardens

8. St.

1 comment