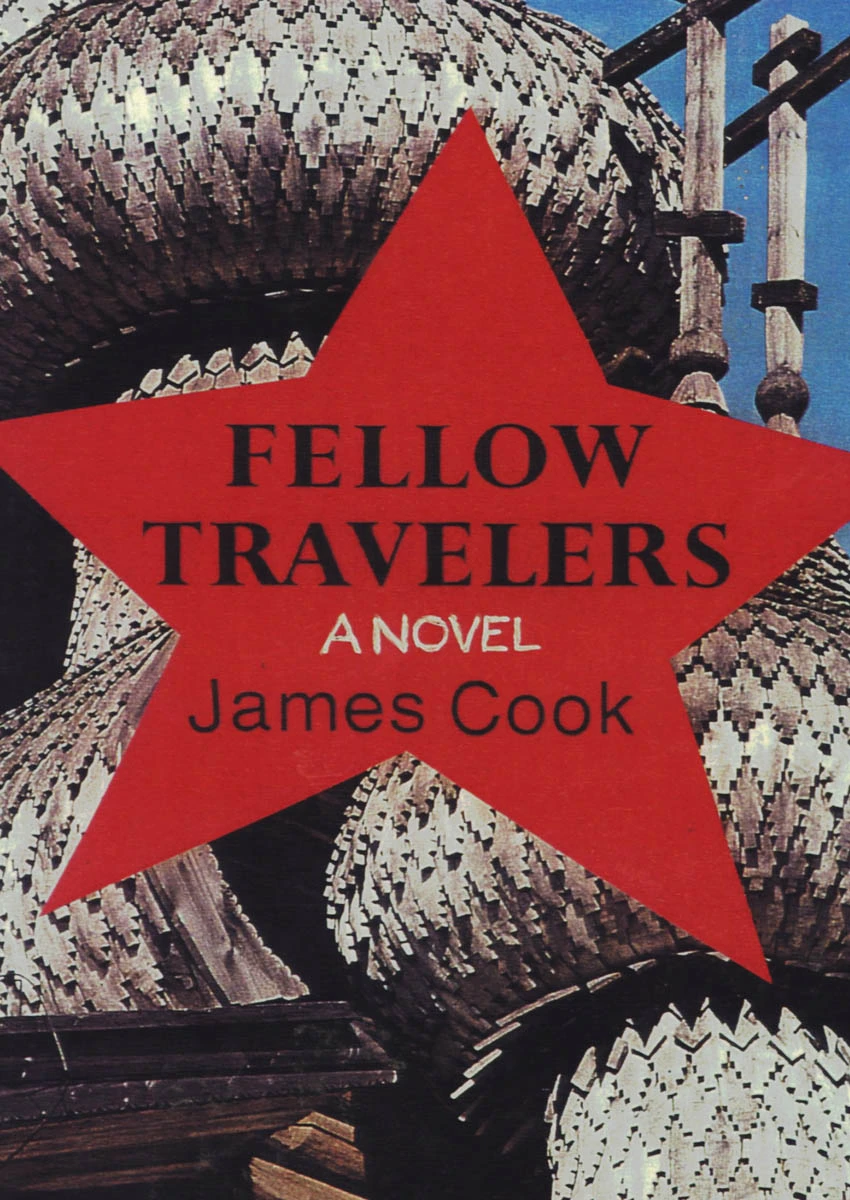

Fellow Travelers

Fellow Travelers

A Novel

James Cook

New York

For the trinity of my life

Claire

Karen Cassandra

To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he’s doing is good.… Ideology is what gives evildoing its long-sought justifications, gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination and makes his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others’ eyes.

—Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn

Contents

I. An American Family: New York, 1922

II. Spring’s Awakening: Platinumgrad, Moscow, 1922–1924

III. Parallel Lives: Moscow, 1924–1929

IV. A Ticket to Leningrad: Moscow, 1929–1931

V. Fausts in America: New York, 1931–1976

I. An American Family

New York, 1922

i

What I always remember first when I think back on that time so long ago, nearly sixty years now, is the mountains, rising like a wall above the valley. They were capped in snow all year round. The rock underneath—schist, granite, how would I know what it was—never broke clear. In summer, the snows receded somewhat, shrank like frost on a windowpane, and then spread back again as summer moved into fall and winter. Lower down, the gray rock emerged in sheets and drops and terraces, unbroken by trees or shrubs or anything else. The air was too cold, the cliffs too steep, for anything to flourish other than lichen or an occasional flowering plant caught in a crevice of the rock.

And then came the trees, on the lower slopes, pine trees, stunted and gray, that clung there in the winds off the Arctic. At the bottom, five thousand, six thousand feet maybe more, there was the valley itself, rocky and dry, paved with pebbles, cobbles, and boulders, and covered with dust as fine as talc. In winter, the wind uprooted the brushy plants that grew there and sent them rolling along the valley floor like tumbleweeds in one of those old western movies.

The houses where all of us lived—Manny and I, the men who worked in the mine and their women, our women if we wanted them—clung along the side of the creek, veered and leaned in the wind, thrown together out of whatever wood or corrugated iron you could find here at the end of the world. Most of them were barracks-like log cabins, but, their scale aside, they didn’t look at all like the ones I remembered from books like From Log Cabin to White House (that wasn’t Abe Lincoln, as I remember, but Garfield). The logs were slabbed and vertical rather than horizontal, and the cracks were filled with clay. Besides these, there were a number of shelters thrown up by the Mongols in the mine crew, structures called yurts with broad overhanging roofs strung with animal skins.

A rocky road ran through the valley, burrowed through what we talked about as the town, and linked the railroad terminal ten miles to the south to the mine a half a mile or more up the slopes of the mountain. But you never used the road except when you had to. We stockpiled the output from the mine in spring and summer, and then moved it by sledge over the deep snows to the railroad in winter. The mine was the reason for everything. Without it, none of the 736 people who lived there—miners, families, ourselves—would have had any reason to stay.

It was a forbidding place, freezing in winter, mosquito-infested in summer, hot, intolerable and seductive only in spring when for a few weeks the rains turned the floor of the valley into a carpet of flowers. I didn’t recognize any of them. I may have come from a city halfway around the world—4,500 miles away, farther than that if you went the wrong way—but I had spent five years living in the country, and I knew enough to be able to tell a sore-eye daisy from a devil’s paintbrush, a dogtooth violet from a yellow cowslip.

I lived there in that place under the mountain for less than a year, from the late summer of 1922 to the spring of 1923, and if this was supposed to be the great adventure of my life, at the time I would happily have done without it. For eight months there was nothing but misery—stifling heat, dust, then bone-aching cold, discomfort, and boredom—and I could hardly wait to escape that town—that country, that world. Now I am no longer sure. Would I have wanted to round out my life without ever having experienced it? I don’t think so. I had gone to the end of the earth, I had dwelt in the mountains of the moon, and now after all these years I tingle a little with excitement just thinking about it.

My brother Manny had gone to Russia the year before, the summer after Pop went to jail. The idea was to see the world and collect some money the Soviet government owed us for medical supplies like codeine, camphor, morphine, quinine, and gauze. Manny didn’t get the money, but he wound up with a platinum concession instead; a mine, town and workforce beyond the Urals in Siberia.

1 comment