Masculinity, according to this view, was a disease which could only be treated through the constant application of patchouli oil.

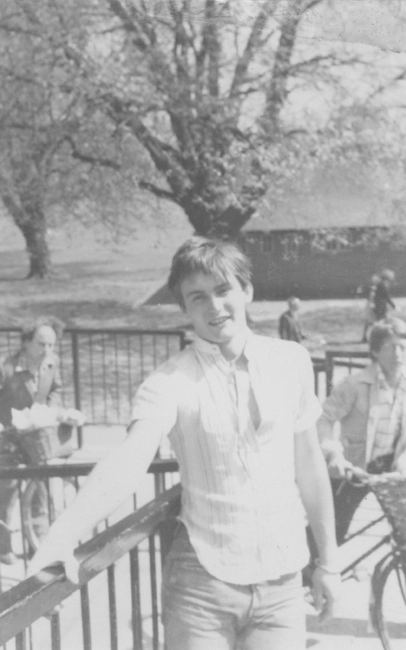

Me at fifteen: a confused mix of pretensions and patchouli oil.

Steve Stephens was an antidote to this mess of competing stereotypes. During the couple of months my father was away, Steve did his best to make a man of me, in his own broad sense of that word. He took me trout fishing, the two of us standing freezing in a rushing creek in the snow country, neither of us catching anything, probably because I was talking all the time. (I hadn’t previously found many adults willing to listen.) He taught me how to cook a trout, just in case I ever managed to hook one. You set a fire, heat a frypan with butter, then slip in the fish. If you lit a cigarette at the point you began cooking, the trout would be ready to turn when you finished the smoke. You’d then light another cigarette in order to accurately time the cooking of the other side.

He also showed me his poetry and made me read other people’s verse. He talked to me about life. He pointed out sunsets. And he took me hunting.

On the day we went hunting, I lay on my stomach and pulled the trigger. On the tenth or twelfth attempt I shot a rabbit. All these years later I can see its death, the small spring upwards when the bullet hit. Steve, being Steve, said the only reason to shoot another creature was for food, so it was my responsibility to skin the rabbit for eating. In the end he volunteered to do the eating, but I remember skinning the poor tiny thing, standing in the gathering dusk and pushing my hand into the warm glove between the skin and the body. That day in the bush is sharp in my mind, with a mix of gratitude and nausea.

Steve was generous with his time. If I had to go somewhere he would offer to drive me. I’d feel guilty and decline. Sometimes he’d insist and I would thank him profusely as we drove along. He’d just shrug and flash me his lopsided smile: ‘It’s just turning a wheel, son.’ Years later, when someone thanks me for giving them a lift, I repeat Steve’s phrase: ‘It’s just turning a wheel,’ but rarely explain the reference. For me, it’s a nod across time to thank Steve for his kindness.

My father eventually returned from his break in Britain and took up the reins of the household. Steve moved into his own place. I missed him, although it’s important to say that Ted put some effort into looking after me. He was certainly consistent when it came to dinner – with a never-ending supply of lamb chops and potatoes, a dish we’d enjoy on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Sunday nights. (On Saturday, he’d add half a grilled tomato just to mark the festive mood.) His efforts were marred only by an inability to leave alcohol in the bottom of any bottle within reach. By early evening, every evening, he’d be one gin short of a Hogarth etching.

With each week, he seemed to slip deeper into a slough of despond. His newsagency backed onto a car-park, on the other side of which was a French restaurant of the 1970s kind called Charlie’s, all snails, pâté and Steak Diane. He took to lunching there every day, polishing off a bottle of red along with the Steak Diane, then retreating to his office at the back of the newsagency. At night, he’d come home at six or seven and cook dinner as he got stuck into the Scotch and soda, producing the soda with the assistance of a brushed-aluminium siphon. It was a device that was seen as sophisticated for reasons that now seem unclear, producing soda that was either entirely flat or so fizzy it would explode and drive all the Scotch out of the glass onto the floor. It was a wonder that, thus impeded, my father managed to get so much of the Scotch into himself.

After a year or two, my father met a woman – a widow of similar years to his own.

1 comment