At the hospital, the doctors administer a general anaesthetic and the pain drops away as the boy counts back from 100: 99, 98, 97, 96 . . .

My parents must have come down to Canberra to see me in hospital, but I don’t recall their visit. I just remember the doctor as I came out of the anaesthetic. He sat on the edge of the bed and said, ‘I don’t know if you understand what I’m talking about, young man, but if you had been just an hour later then you might have missed out on children of your own.’ I have since checked this with a specialist and his diagnosis may have been overly dramatic, as you’d still have one good ball. Still who wants to look like Hitler?

Oh, glorious chapter that has an opportunity for two testicle-related ballads:

Hitler has only got one ball,

Göring has two but very small,

Himmler is somewhat sim’lar,

But poor Goebbels has no balls at all.

I don’t know why my parents left Sydney and bought the newsagency; in retrospect, it makes little sense. The explanation given at the time was that my father was sick of working for others and wanted his own business. Yet both my parents had good jobs and seemed to relish being part of what passed for high society in Sydney. Perhaps my father’s drinking was starting to build in a way that gave him trouble at work; maybe my mother was having an affair. I have some recollection of angry words between my parents, centred on a particular man, a famous businessman. More likely, though, it was just the allure of money: a couple they knew had a newsagency in Sydney’s Double Bay and had installed their 25-year-old son as the manager. He earned so much money he’d purchased a suit worth $200. That sum of money – $200 – was such an incredible amount for a suit. My parents talked about it endlessly. The newsagency business must be a goldmine to allow the purchase of such a suit. Life twists and turns on the smallest of things and, in all likelihood, it was that suit which sent me to Canberra – and thus to my particular adolescence, my particular school, my particular teachers.

And, in a way, to a right ball that, ever since, has hung rather low.

After a few months my parents arrived in Canberra. I said farewell to the Hutchinsons with a stab of regret, moving my stuff from the upstairs bedroom, saying goodbye to Honey the dog, the overgrown garden and the snug kitchen. My parents rented a large house with a separate wing – consisting of two rooms and a bathroom – into which I was installed. There was even an intercom to the rest of the house, via which I could be summoned to dinner. This was fun at the time but, as I type this, does seem a rather obvious metaphor for my emotional separation from my parents. I apologise, dear reader, for constructing my childhood from such heavy-handed literary devices. In my next life, I will insist that reality expresses itself through more subtle tropes.

Sitting in my separate wing, I began to develop a passion for Elvis Presley, bordering on monomania. Looking back, it seems entirely clear that I was reaching out for some sort of father figure, and found one in the most unlikely place: inside a white jumpsuit spangled with rhinestones, satin straining around the belly. With access to a newsagency I would bring home great piles of newspapers and magazines and search out the merest mention of the King. I’d cut out the paragraph and Clag-glue the clipping into a massive scrapbook. Elvis, by this time, was past the height of his fame, so the clippings were meagre: tiny mentions of his films screening at midday on Channel 7, the scraps so small that my painstaking annotations – ‘TV Week, June 26, 1971, page 34’ – took up more space than the clipping itself.

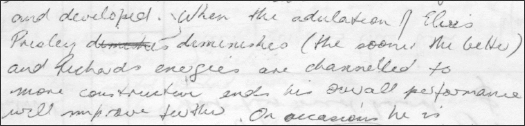

By the end of that first year at school, my report card put it bluntly: ‘When the adulation of Elvis Presley diminishes (the sooner the better) and Richard’s energies are channelled to more constructive ends, his overall performance will improve further.’

I’m aware you’ll think this is an attempt at comic exaggeration, so I’ve scanned in the report so you can see for yourself:

Alas, by the start of the second year of school, my obsession with Elvis had grown even stronger. The walls of my separate wing were papered over with Elvis posters and record sleeves. I insisted on completing a school project on Elvis in which I displayed photographs and text around the headline: ‘1954 to 1972 – 16 great years of Rock and Roll’, my skill at Letrasetting proving superior to my talent for mathematics.

At this point I moved into a class with a new English teacher: Mr Phillipps. In a Canberra private school in the 1970s, he was everybody’s image of an old-fashioned British academic. The final two ‘p’s in his name seemed to pprove it.

1 comment