To his right, two stakes, each planted at a corner of the pedestal, were joined at their uppermost tips by a long, supple thread that sagged under the weight of three objects hanging in a row, displayed like fairground prizes. The first item was none other than a bowler hat, the black crown of which bore the word “PINCHED” written in dirty white capitals; then came a dark gray suede glove turned palm outward and decorated with a “C” lightly traced in chalk; and last hung a light sheet of parchment covered in obscure hieroglyphs, its header boasting a rather crude sketch of five caricatures made plainly ridiculous by their poses and exaggerated features.

Imprisoned on his pedestal, Nair’s right foot was collared by a noose of thick rope firmly anchored to the solid platform; like a living statue, he performed a series of slow, regular movements while rapidly murmuring a string of words he’d committed to memory. In front of him, placed on a specially shaped stand, a fragile pyramid fashioned from three joined pieces of bark captured his full attention; the base, turned toward him and slightly raised, served as his weaving loom. Within reach, on an annex to the base, was a supply of fruit husks covered on the outside by a grayish vegetal substance much like the cocoon of a larva about to transform into a chrysalis. By pinching a fragment of these delicate envelopes with two fingers and slowly pulling back his hand, the youth created a flexible bond, reminiscent of the gossamer threads that stretch across the woods in springtime. These imperceptible strands helped him weave a subtle and complex embroidery, for his two hands worked with unparalleled agility, crossing, knotting, intermingling the fairylike ligatures into graceful patterns. The phrases he tonelessly recited served to regulate his perilous and precise maneuvers, for the smallest slip could have caused the whole structure irreparable damage. If not for the aid of a certain formula memorized word for word, Nair could never have reached his goal.

Lower down, to the right, other toppled pyramids at the edge of the pedestal—their tips facing away from the viewer—allowed one to appreciate the effect of these labors, once completed; each upright base was indicated by almost nonexistent tissue, more ephemeral than a spider’s web. In each, a red flower held by its stem irresistibly drew the viewer’s gaze through the imperceptible veil of the ethereal weave.

Not far from the Incomparables’ stage, to the actor’s right, two stakes set four to five feet apart supported a moving apparatus. A long pivot extended from the nearer of the two, around which a scroll of yellowed parchment was compressed into a thick roll; solidly nailed to the farther stake, a square board laid as a platform served as base for a vertical cylinder slowly made to revolve by clockwork.

The yellowish scroll, unspooling tautly over the entire length of the intervening gap, wrapped around the cylinder, which, turning on its axis, ceaselessly pulled it toward the other side, gradually depleting the pivot that was forced to spin along with it.

The parchment showed groups of savage warriors, rendered in broad strokes, parading by in highly varied poses. One cohort seemed to be in mad pursuit of the fleeing foe; another, crouching behind an embankment, awaited its moment to burst forth; here, two equally matched phalanxes engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat; there, fresh troops surged bravely forward with grand gestures toward a distant melee. The continual procession offered endless surprises, owing to the infinite number of effects obtained.

Opposite, at the far end of the esplanade, rose a kind of altar preceded by several steps covered with a thick carpet. From a distance, a coat of white paint veined with bluish lines gave the whole the appearance of marble.

On the Communion table, represented by a long board placed halfway up the structure and covered with a cloth, one could see a rectangle of parchment dotted with hieroglyphics standing near a heavy cruet full of oil. Next to this, a large sheet of stiff luxurious paper bore the title, “Reigning House of Ponukele-Drelchkaff,” written scrupulously in Gothic letters. Beneath this heading, a round portrait, a kind of delicately colored miniature, depicted two young Spanish girls aged thirteen or fourteen, coiffed in the national mantilla—twin sisters, judging by their perfect resemblance. At first glance, the image seemed part and parcel of the document; but upon closer inspection, one noticed a wide band of transparent muslin, glued onto both the circumference of the painted disk and the surface of the durable vellum, that melded the two objects seamlessly, though they were in fact separate. To the left of the dual effigy, the name “SUANN” paraded in large capitals; beneath it, a genealogical chart comprising two distinct branches, descended from the two lovely Iberians who formed the apex, occupied the rest of the sheet. One of these lineages ended with the word “Extinction,” in letters almost as large as the title, clearly meant to catch the eye; by contrast, the other, stretching a bit lower than its neighbor, seemed to defy the future with the absence of any concluding sign.

Near the altar, to the right, a giant palm tree flourished, its admirable breadth attesting to its great age; a handwritten sign affixed to the trunk offered this commemorative phrase: “Restoration of the Emperor Talou IV to the throne of his forefathers.” Off to one side and sheltered by the palms, a stake planted in the ground supported a soft-boiled egg on the square ledge of its upper tip.

To the left, at an equal distance from the altar, a tall plant, but old and pitiful, made a sorry complement to the resplendent palm; this was a rubber tree, its sap run dry and in a state of near rot. A litter of branches placed in its shade supported the recumbent corpse of the Negro king Yaour IX, classically costumed as Gretchen from Faust in a pink woolen dress with alms purse and thick blonde wig, its long yellow plaits, thrown over his shoulders, reaching almost to his legs.

To my left, backed against the row of sycamores and facing the red theater, a stone-colored edifice looked like a miniature version of the Paris Stock Exchange.

Between this structure and the northwest corner of the esplanade stood a row of life-size statues.

The first showed a man mortally wounded by a spear plunged into his breast. Instinctively, his two hands clutched at the shaft; his body arched back on the verge of collapse as his legs buckled under the weight. The statue was black and at first appeared to be all of a piece; but gradually one’s eye discovered a multitude of furrows running in all directions, forming clusters of parallel striations. In reality, the work was composed entirely of numerous whalebone corset stays cut and molded as the contours dictated. Flathead nails, their tips evidently bent beneath the surface, jointed these supple strips together so artfully that not the slightest gap remained between them. The face, its nose, lips, eyebrows, and eye sockets faithfully reproduced by minutely arranged little sections, bore a finely rendered expression of pain and anguish. The shaft of the weapon buried in the dying man’s heart suggested some great difficulty overcome, thanks to the elegant handle that showed two or three stays cut into small rings. The muscular body, clenched arms, and nervous, crooked legs all seemed to tremble or suffer, due to the striking, flawless curves imposed on the invariable dark-colored strips.

The statue’s feet rested on a simple vehicle, its low platform and four wheels composed of other black, ingeniously combined whalebone stays. Two narrow rails, made from some raw, reddish, gelatinous substance, which was none other than calves’ lungs, ran along a dark wooden surface and, by their form if not their color, created the precise illusion of a section of railroad track. It was onto these tracks that the four immobile wheels fit, without crushing them.

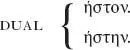

The surface supporting the tracks formed the top of a jet black wooden plinth, the front of which bore a white inscription with these words: “The Death of the Helot Saridakis.” Below it, also in milky letters, one saw this phrase, half-Greek and half-French, accompanied by a slim bracket:

Next to the helot, the bust of a thinker with knit brow wore an expression of intense and fruitful meditation. On the stand one could read the name:

IMMANUEL KANT

After this came a group of sculptures depicting a thrilling scene. A cavalry officer with the face of a thug seemed to be interrogating a nun flattened against the door of her convent.

1 comment