I had expected it to be like going to the movies—that we’d be able to sit back in our velvet seats in Row J and soak up the experience—but this was no passive activity. It was visceral.

Onstage, however, it was clear that Mick really wasn’t up for this. The kids, caught up in Bowiemania, were going crazy. Mick just wanted them to quiet down and listen to the songs, but that was not going to happen, not that night.

Mick may have been the greatest living sideman, perhaps second only to Keith Richards, but he was never really comfortable center stage.

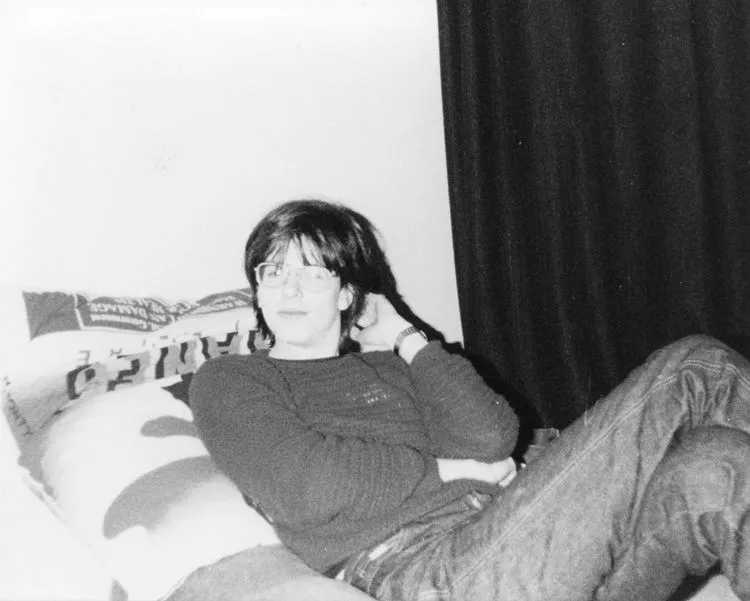

Nick and I both wore chiffon without needing much encouragement, and we both loved the clothes, the hairstyles, and the makeup that helped make Britain’s glam-rock era so great. Neither of us was old enough, really, or had the dough, to fully express ourselves in the way we would have liked, and besides, the glam movement had peaked on that Bowie tour the previous summer, but we found our level.

Bryan Ferry’s sartorial direction was having its effect, and all the boys were going through their dads’ closets to find his old demob suit; the forties stylings, the baggy double-breasted suits like Bogie wore in Casablanca.

Dad’s fit me perfectly. But then there was the transsexual glam aspect, and we found ourselves mixing it up with ladies’ blouses. At British Home Stores, in the city center, there was a huge floor filled with two-piece ladies’ suits from the forties and fifties to be had for a song. Vintage heaven. Some of those jackets were divine, and fitted both Nick and me. Throw in a little chiffon, maybe an animal-print scarf from Chelsea Girl, and you were away.

“You’re not going out dressed like that?” our parents would cry.

“Don’t you worry about it, Father,” Nick would tell his dad defiantly, as I applied a little lip gloss in their bathroom.

“Oh, leave them alone, Roger,” Sylvia would say. “They’re just having fun.”

We often drew insults from construction workers.

Nick was a little more outré than I, having the protection of a girlfriend, Jane, which gave him some cover.

One evening, on the train back to Hollywood, we were sitting in the front seat of the carriage behind a glass panel. A gang of denim-clad bozos started banging on the glass.

“We are gonna get you! You fairies are fucking dead!”

Nick and I were shitting ourselves, but we edged ourselves as coolly as we could to the far end of our carriage. Where was the guard?

I needn’t have worried. Being with Nick, somehow we magicked ourselves out of danger. By the time the train pulled up at Whitlocks End, the bozos had disappeared.

We had other things in common as well as our dangerous tastes in clothing and music: He was also an only child, our birthdays fell in the same month—June (we are both Geminis)—and our favorite board game was Chartbuster.

“Throw a six—your first single advances ten places!”

This pop music business looks pretty easy.

The next concert Nick and I went to together was Roxy Music in September at the Odeon. It was a Saturday, so in the afternoon, during our usual trip into the city, we found ourselves in the theater lobby where we made the acquaintance of two guys, Marcus and Jeff, older than us and both serious Roxy fans. They told us that the band were in the building and if we hurried down the alleyway that led down the side of the Odeon, we could hear them playing. This is where I learned about the secret world of the sound check. The logistics of an artist’s show almost always require a visit to the venue in the afternoon, when the wires and mics and amps and drums are tested to make sure the triumphant arrival onstage later that night is not hampered by any technical oversights. There were a dozen or so kids standing there in Roxy regalia, T-shirts, scarves, haircuts, beside a purple articulated truck that had been backed up to the stage door to unload the gear. We couldn’t see Roxy, but we could hear them, vaguely, playing songs from their new album, Country Life. Then the music stopped, and as if on cue, a black Mercedes limousine rolled down the alleyway.

In a sudden frenzy of activity, the band rushed out of the stage door and, without stopping, piled into the comfort of the car, which then took off at speed up the ramp toward New Street.

A girl yelled, “They’re going to the Holiday Inn! I know a shortcut!” and off we went, Birmingham’s twelve biggest Roxy Music fans sprinting across the city at full pelt.

This was a club I wanted to belong to!

She knew her stuff, this girl; we were waiting under the hotel awning when the car drew up.

I don’t remember Ferry, but I do remember guitarist Phil Manzanera, who was the tallest man I had ever seen in my life. Maybe it was the platform boots. Keyboard player Eddie Jobson took time to say hello and sign autographs. I asked one of the drivers to give me the champagne cork I spotted on the back shelf of the limo. I was proud of that. Was this strange behavior for a fourteen-year-old suburban boy? I didn’t think so.

Nick’s and my gig-going gathered momentum. I still have the ticket stubs from those years. The Faces show came in December, Queen, Genesis—big gigs by big bands, usually at the Town Hall or the Odeon. And if it was an artist we were real fans of, such as Iggy Pop, touring with David Bowie, or Mott the Hoople, we might find ourselves standing under those hotel awnings again or waiting by the stage door listening to the sound check.

10 The Birmingham Flaneur

I took my skiving up a notch when I began spending the entire school day in the city of Birmingham.

1 comment