Only “Anarchy in the UK” wasn’t just a record, it was a revolution. A song that changed everything, not only for me, but for my entire generation.

I remember coming home after I bought it. I was sixteen. It was November. I charged up the stairs to my bedroom—Dad’s hi-fi had been relocated—carried the speakers to the windowsill, and faced them outward, opening the windows wide, playing the record as loud as the system could handle, out over the neighborhood, over and over and over again, on repeat as loud as the volume would go.

Fuck the neighbors. Fuck them all.

“I’m not who you think I am! This is me!”

After I had played the song a dozen times, I was seized by an urge.

“Where’s that fucking guitar? Where is that guitar?”

I dug it out and started banging away at it, two strings, out of tune, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, to “Anarchy in the UK.”

And it fucking rocked.

The acoustic guitar salvaged from the closet wasn’t going to cut it. I needed an electric guitar and found a Fender Telecaster copy in a secondhand music store for fifteen pounds.

It had a tired “authentic” sunburst finish that did not suit my aesthetics. With Dad’s help, I sprayed the guitar body ermine white, a color Dad had knocking around in his garage, the color of his second Ford Cortina. I acknowledged that six strings was above my capabilities and decided, made a choice as it were, to use only five strings. In actual fact, I didn’t need all of those. On the Buzzcocks’ defining punk classic “Boredom,” Pete Shelley had played a guitar solo using only two notes. This was the mood of the times.

I was still best friends with David Twist, the kid who had introduced me to Nick. I loved spending time at the Twists’ house, because his parents allowed us, even encouraged us, to bang away at our instruments in his bedroom, David having a small amplifier his dad had built for him.

Nick was spending more and more time with his girlfriend, Jane. Whenever I visited Nick’s house, I felt like the third wheel. That was not the case at David’s, who was another single, solo loser like me. As cool as making music felt, the level that we were operating at was downright nerdy—no girls allowed, yet.

David sang, I bashed my guitar, and we created mock concert events, complete with “lights down,” “lights up,” and “intro music.” Songs were written, and John West and the Sardine Cans gave their inaugural performance to both sets of parents at Christmas. Classic stupid name. Meaningless.

Needing to expand the sound, I convinced one of my friends from school, Roy Highfield, who had a snare drum and a hi-hat, to buy a tom-tom, and then another friend emerged with a bass guitar. We were a band.

And that was it, man, that was it. It was like lighting the blue touch paper. This is what I wanted to do. I knew I didn’t want to play football in the park.

We moved our gear into Gareth’s, Gareth “the bass.” His family lived in a big house with a drive and space around it, so it was a suitable place for us to practice. Plus he had two sisters, Heidi and Debbie, who liked to sit and watch us, which was encouraging. Even Gaz’s mom was cute, so there were women in the house that you could play to, which was super important.

I believe it’s known as the muse.

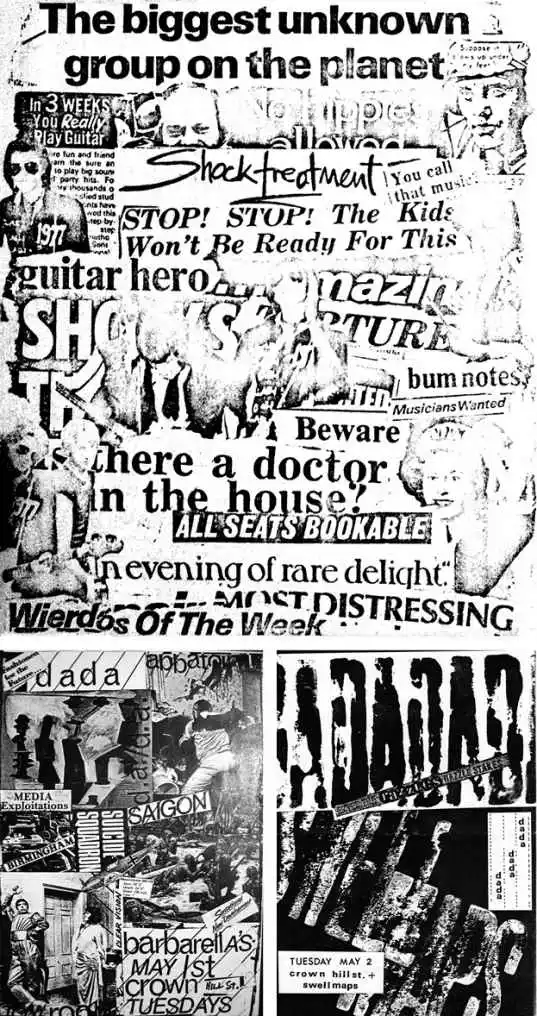

12 Shock Treatment

David, Gareth, Roy, and I were on Punk-rock 101, and we renamed our band Shock Treatment, from the Ramones song “Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment.”

We started writing songs. Simple, to the point, and very much of the time. “Freedom of Speech,” “I Can’t Help It,” and “UK Today” could have been written by almost any British teenager that week, although titles such as “Cover Girls” and “Striking Poses” suggest interests other than the political. There was nothing profound, though. It was almost all imitation, but they were songs, with verses and choruses and rudimentary guitar solos. A couple of cover songs were learned also; the Stooges’ three-chord dirge “I Wanna Be Your Dog” was a song anyone could get right, and The Who’s “Substitute,” which the Pistols had done.

I wasn’t the singer, the front man, but I knew what we had to do. I knew we needed a gig, so I got us one, sweet-talking the school committee into letting us play at the summer dance, a few weeks away in June 1977.

I had lost my taste for Top of the Pops and supergroups like Genesis.

1 comment