In the top right-hand corner, we dropped in a photo of the three of us, with our facial features strangely absent. Maybe it was art—or maybe I just overdid the contrast on the college photocopier.

The song titles were: “Soundtrack,” “Aztec Moon Rich,” “Take (The Lines and the Shadows)”—which could be one of Simon’s titles—“Hold Me/Pose Me,” “A Lucien Melody,” and “Hawks Don’t Share.”

I was very proud of this first attempt at album-making and decided to offer it as my year-end project. Each student was allotted a certain amount of space in the main hall to display the fruits of their labor. I covered my wall space with a shiny black plastic garbage bag and placed the solitary cassette tape on the table in front of it. It looked pretty good.

There was a certain amount of chutzpah required to keep a straight face as the college faculty and my fellow students circled my presentation. I had taken the Steve Duffy model of freedom of interpretation to another level.

(Professor Grundy picks up the cassette, handles it gingerly.)

Grundy: And what is this exactly?

Me: It’s what I’ve been doing for the last six months.

Grundy: And what are you hoping to do with it?

Me: Get a record deal.

Grundy: It doesn’t really relate to your course work though, does it?

Me: Why should it? Haven’t you been encouraging us to think more freely, about what is and isn’t art? This is art because I say it is.

(I couldn’t have cared whether he passed me or not.)

Grundy: Well, I am glad you’ve learned something in your time here, Nigel.

That was my last day in academia. A few weeks later I got a letter telling me I hadn’t been accepted for a place on any of the BA courses I had applied for.

Secretly, I was happy. All I wanted to do was make music, refine these ideas we were having as a band, and play as often as possible.

But I had to explain this to Mom and Dad, as I wanted to carry on living at home.

I approached them with far greater humility than I had my college professors. What I was proposing—to not get a job—went against the grain of everything they knew. They saw my music-making as a hobby at best, something to smile about but not to make a career of.

My cause wasn’t helped by the fact that Dad had been made redundant—he liked to call it taking early retirement—at fifty-seven, and if I could get this through, for a while we would be signing on for state benefits together.

“I just need some time, Mom, Dad. This is what I really want to do.”

“I don’t know. Jack, what do you think?”

Their disappointment was palpable. They both had dreams of their son at university. This was a big lump for them to swallow.

I had to further my argument. “I’m not saying I don’t want to do anything. I’m not going to be sitting around the house. I’ll be working at the music. But I need to do it full-time.”

Dad was pretty out of it. The debacle at work that had led to his “early retirement” had left him stunned and out of ideas. The rebel in him wanted to support me.

“I suppose we could give it a try. One year only.”

That was all I needed. I could feel it. I could barely contain myself. In a display of emotion that was rare at number 34, I hugged them and cried because I knew the significance of what was happening.

Mom and Dad giving me the benefit of the doubt and allowing me to pursue my goal for twelve months was the best gift they ever gave me.

There was not a moment to lose.

15 Everybody Dance

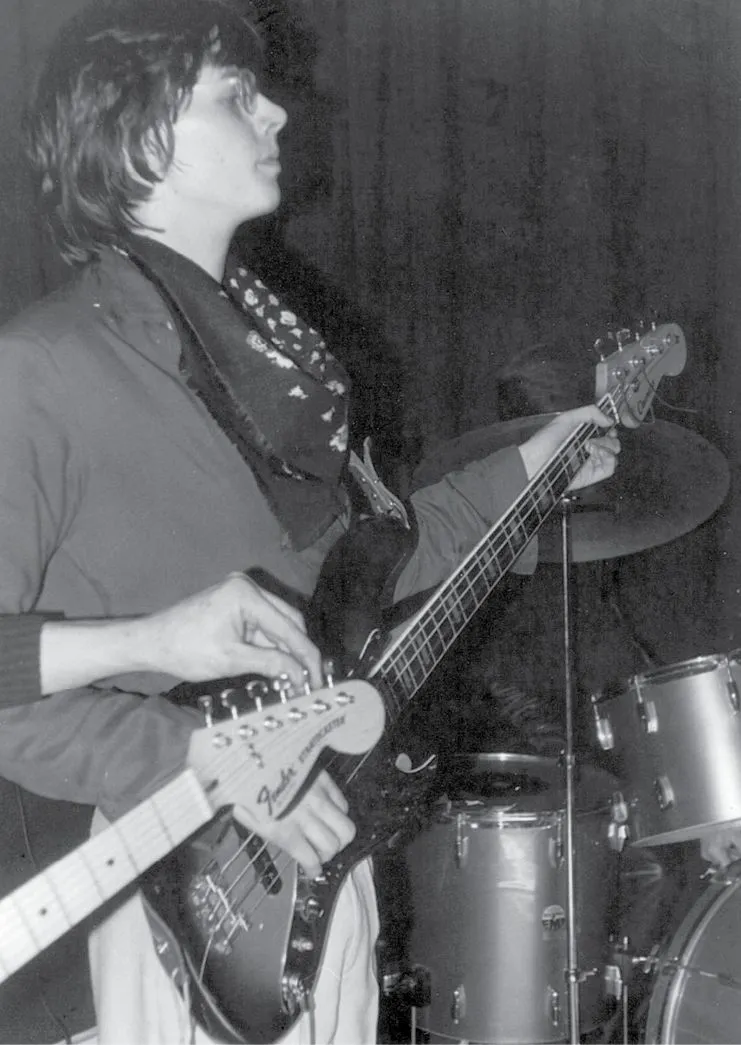

Duran Duran played next at the Cannon Hill Arts Center on May 8 (tickets fifty pence) and then at Barbarella’s on June 1.

Walking back to Hollywood from the Maypole bus terminus, Nick and I were convinced Duran Duran were going somewhere. We had really connected with the Barbarella’s crowd. There was enough positivity in their reaction to what we were doing to encourage us. We were on the right track.

And then, disaster.

Days and days passed after the Barbarella’s gig where neither Nick nor I could get hold of Steve or Simon. What the fuck was going on?

And then the word came down the wire; they were both making music at a Cheapside squat with several members of TV Eye, another local band, my oldest friend, David Twist, among them.

I raced around to Nick’s home on Mill Close.

“Can you fucking believe it?” I said.

“Wankers!” retorted Nick.

This was not a time to play Chartbuster. The stakes had gotten too high for that.

We were distraught. But not destroyed.

1 comment