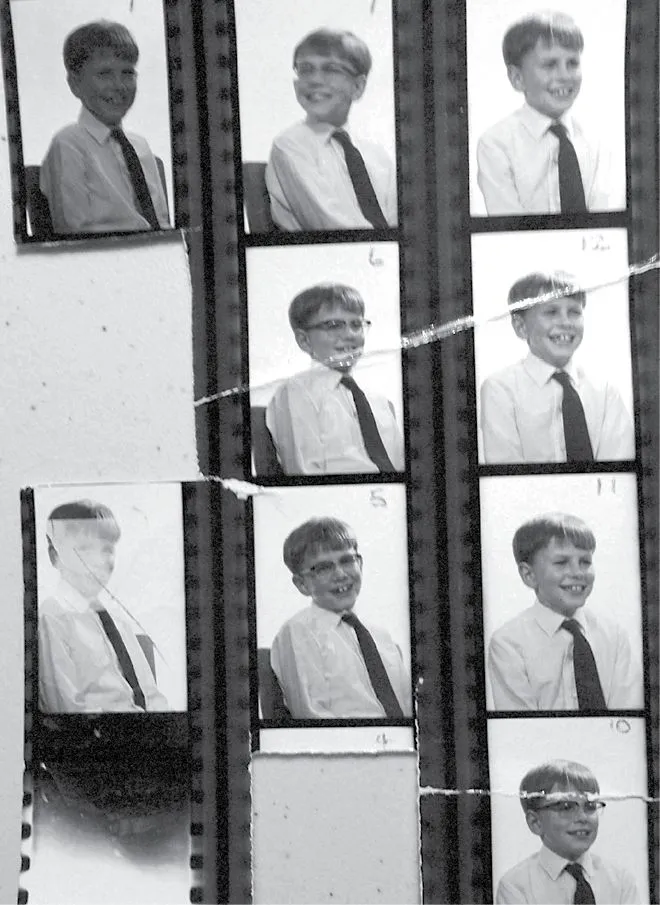

My clearest memory of first-year infants is of the Monday I showed up wearing my new National Health standard-issue thick-rimmed glasses, at age five. The teacher suggested I stand on the desk so everyone could get a good look at the new me. It was like, “Hey, just call me four-eyes, guys!” I’m sure Mrs. Gilmore hadn’t meant it to be humiliating but, for a five-year-old, it was.

Jammie Dodgers were not the only religion handed out at Our Lady of the Wayside. Catholic dogma was high up on the curriculum, with religious knowledge—or “RK”—nestled cozily next to math, history, and geography. Two plus two equals four, the Battle of Hastings was in 1066, the capital of France is Paris, and Jesus turned water into wine at the wedding in Cana.

Despite all the hours I had spent at church, all that ceremony, all those readings, the music, the incense, I still didn’t get it. Intellectually, it never made sense to me.

Like a member of the crowd at the feeding of the five thousand, I sat there, scratching my head, trying to figure out how on earth Jesus could have made all that food out of five loaves and two small fish. How? Why? Because he was Jesus? Because he was The Man? What was I missing?

But one thing you learn early on is that asking how or why is frowned upon in the Catholic Church. Not for us the intellectual rigor of the Jewish religious people. Or the spiritual curiosity of the Buddhists.

For us, ignorance is a matter of pride.

It’s what I call “the Catholic Caveat,” and it’s a minor stroke of ecclesiastical genius, because what it says is this: If you have to ask, then you don’t have faith, and if you don’t have faith, you are totally fucked, because lightning will come searing through your bedroom window that very night and BLOW YOU OFF THE FACE OF THE EARTH!

It can be a scary and confusing world to grow up in.

5 A Hollywood Education

Dad smuggled in some coded messages that there may be life outside St. Jude’s and Our Lady of the Wayside.

At Christmas 1966, when I was six and a half, he brought home the Wilmot-Breeden works calendar. It was not to be hung in the kitchen, this calendar, or any of the other “public spaces” in 34 Simon Road. What Dad did was take the scissors to the thick, shiny pages and separate them, creating twelve images from around the world: Red Square in Russia, Sydney Harbour Bridge, an ancient village of red brick and tile sitting on an unimaginably blue sea, and another, of the most gorgeous raven-haired temptress, dressed in red, atop a black horse that matched her hair.

Dad mixed up some wallpaper paste and glued the pages to my bedroom walls, alongside and over my bed. Above my pillows there already was the ubiquitous Jesus on the cross, the crucifix that no self-respecting Catholic is ever far away from. Now he had some competition for my imagination.

Jesus: tortured; blood dripping from the nails that had been so brutally hammered home through his hands; the crown of thorns. It was a nightmare vision, and the intention was to give Catholics a conscience. All it gave me was guilt.

Dad’s presentation of beauty and adventure, of what could be found across the seas and oceans, seemed to be saying to me, in a whisper, “There’s more to life than this, lad. It’s not just about Hollywood, Him, and school.”

Gazing up at those pictures, illuminated only by the streetlight that filtered in through the curtains long after my lights had been turned out, night after night, was where all my dreams of romance, travel, and escape began.

The next step in the home education that Father introduced was to begin drilling me on geography; capital cities, rivers, and flags became favorite subjects of mine, and I fast became an expert. It’s a useful interest to have when you are on the road six months a year.

I would beg, plead to be quizzed on my geographical knowledge on weekend mornings, when I would climb into bed with Mom and Dad.

“Ask me some rivers,” I would say excitedly, eyes popping out of my head.

Dad would fold up his Daily Sketch, saying, “Can’t you ask him, Jean?”

“I don’t know them, Jack. No good asking me,” Mom would say.

Dad would smile resignedly and say, “Amazon?”

“Brazil!” I would snap back like a piranha. And we were off.

It’s a pretty cozy life, the life of an only child, especially when both parents are present and love is not in short supply. I had a good thing going.

We had three neighbors in the adjoining house, number 36, over the years. The worst of them were police officers. I knew the seventies had arrived when I saw that pale blue police car roll up onto the drive.

They were fascists, man—that was clear from the uniforms.

They didn’t have kids so they were like, “Turn the music down!” “Turn the TV down!” and “No, you are not going to get your ball back if you keep kicking it over the fence!” I thought the husband was a real blockhead and the sight of him shouting at Dad, eyes popping out of his head—“If you don’t sort that son of yours out, I will!”—terrified me.

All I was doing was being a kid. As I got older and music took over, I wanted to listen to music all the time, ideally when no one else was in the house so I could turn it up really loud. To be fair, I had no idea what it must have been like for them on the other side of those paper-thin walls.

My parents hated these confrontations with the neighbors. Mom was very timid, and Dad wasn’t up for another fight. Given that he was a soldier, a hero, I couldn’t understand why he wouldn’t just weigh in there with his fists flying. It was an early lesson in the limitations of my parents’ power.

6 In Between and Out of Sight

I enjoyed learning and acquiring knowledge, but it was a habit rarely manifested in the classroom. Only in the privacy of home, in the snug, close-fitting world of Mom, Dad, and me, did I have the confidence to let fly.

Intelligence needs training, and training includes making mistakes.

1 comment