Manly men doing manly things. Like killing each other.

Around about that age, I had a first thought about a future career, a pilot in the Royal Air Force. I wondered to myself after lights out, did the RAF still fly Spitfires?

The relentless construction of RAF fighter planes and Panzer tanks and ships of the Royal Navy was also a way of scratching at the surface of the great unspoken subject: Dad’s war years. We couldn’t communicate about the subject directly, so I just kept building. Shit, we English kids had it easy; what were the German kids of my generation talking to their dads about? Not a lot, I would find out later, but it did provide impetus for all the great and profound German art and music of the seventies and eighties.

My obsession moved up a notch when I began collecting and painting models from Napoléon’s vast Grande Armée. I particularly coveted bona fide rock stars such as Marshal Murat who, arm outstretched and saber poised, rode into battle on his leopard skin–bedecked steed.

I needed more cash to feed my habit because these figures, imported from France, or their smaller-scale cousins cast in lead, cost a lot more than the Airfix guys. Dad inadvertently gave me another life skill; I became the neighborhood car washer.

Painting all those uniforms in intricate detail on three-inch figurines left its mark on my aesthetic sensibility—the epaulets, the braids, the sashes, and the boots. You can still see an Airfix influence onstage with Duran Duran today. I just can’t seem to shake it off.

• • •

I was also crazy about cars, another passion I inherited from Dad. No one took greater pride in car ownership than Dad, and his relationship with his various cars was almost erotic. Every spare hour he had, he spent it alone in the garage with the car, tweaking, messing, customizing. And if, while driving, the car developed the slightest rattle or vibration, he would go nuts and, as soon as we got home, would disappear, taking the car apart until he found the cause of the noise and silenced it. He invested his entire working life in the British car industry, and any sign of imperfection he considered a personal affront.

Over twenty years, Dad had earned the reputation as the family’s designated driving instructor, having taught many uncles and aunts, nieces and nephews how to become drivers. Ironically, his most famous failure was his own wife, Jean, my mom.

One evening after school, Dad decided it was time to teach Mom to drive. Mom wasn’t sure that was a good idea, and she was nervous about getting behind the wheel of Dad’s prize bull. She knew how attached Dad was to his car and how easily he could get mad. However, we all climbed into the maroon Ford, Dad behind the wheel for now, and drove to a designated lay-by spot out in the country, a few miles from home.

Dad pulled the car over onto the roadside. In front of and behind us were ten-foot piles of gravel. The space between was maybe two hundred yards. Mom and Dad switched seats.

They are both edgy, and I must be picking up on that energy because I am bouncing around in the backseat restlessly, squeezing my body between the two front seats, as I always do, to really get an idea of what is involved in the “lesson.”

First thing Mom does is to push the gear stick into first, not taking into account the use of the clutch (these are the days before automatic transmission arrived in the United Kingdom), and the sound of screeching fills the cockpit.

“Christ, Jean! Don’t crash the gears!”

Mom looks terrified.

“Oh Jack . . . I don’t know, what am I supposed to do? Nigel!”—that is me—“Sit back!”

“You have to push the clutch in, Jean, before you go into gear. Use your left foot,” says Dad.

Once again, Mom tries to engage the gear, but not only do we get the screeching again, this time the car leaps forward in clumsy bounds, bumpa bumpa THUD!

The engine stalls.

“Christ, Jean, what is the matter with you?” Mom’s on the verge of tears, her face beet red.

“Forget it,” she says stubbornly. “I don’t want to drive, let me out.”

She can’t get the door open, and Dad now has his dangerous, furious look on, fit to burst. Then he’s out of the passenger seat, stomping around the front of the car, opening the driver door for Mom to get out. She climbs back into the passenger seat; Dad gets back behind the wheel.

“And you! Sit back! Sit back in that bloody seat!” he says to me. The car exits the lay-by with an uncharacteristic wheel spin.

And that’s it. Mom’s one and only driving lesson is over. Every time it gets mentioned in the future, my role is slowly but surely magnified until I have become the principal cause of the disaster.

“With you jumping around in the back, how was I supposed to concentrate?”

7 Junior Choice

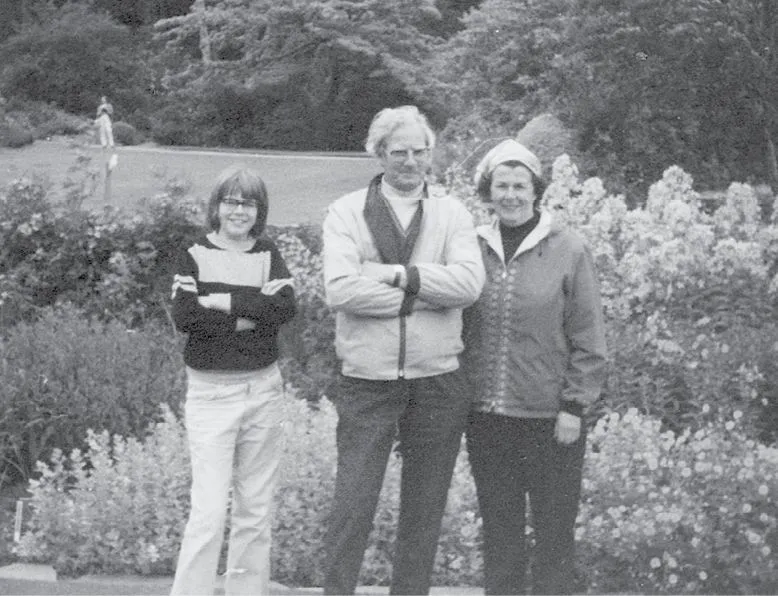

On Saturday mornings, the three of us—Mom, Dad, and Nigel—would gather at the kitchen table for breakfast. On the radio at eight would be Ed “Stewpot” Stewart’s Junior Choice, another terrific bonding opportunity for kids and their parents.

From up and down the country, folk would write in. Ed would begin, “We’ve a letter from Edith Baker in Accrington: ‘Dear Ed, it’s our Jimmy’s eighth birthday on Saturday, and for his party he has asked for a cake with a picture of you on it!’”

Chuckling to himself, Ed would continue: “I can’t imagine anyone wanting to eat that cake, Edith.

1 comment