It was a very different take on land ownership, hunting, politics, love and sex, reflecting the distance between now and then.

Yet the heart of Macnab remains the same: for those times when our lives lose their savour, we can turn to the self-created adventure, the challenge, the game, whether it be poaching, climbing or falling in love. I sent up Mal Duff something rotten in the Alastair Sutherland character, which he greatly enjoyed. He was still urging we should do Macnab for real the last time we had a drink together, before he set off on another Everest expedition. He died unexpectedly from a heart attack in his tent. I miss him still, as Buchan so patently missed and mourned for his brother and the friends who died in the Great War, those whose absence and whose memory so inform this rather wonderful and oddly touching book – a lasting celebration of adventures, hills and rivers and friendships shared.

Andrew Greig

May 2007

To

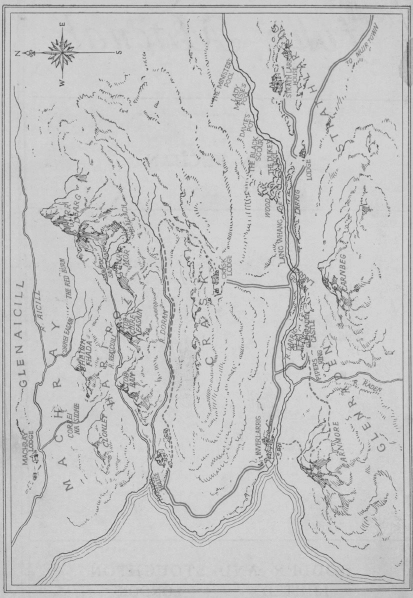

ROSALIND MAITLAND

Contents

1. In which Three Gentlemen Confess their Ennui

2. Desperate Characters in Council

3. Reconnaissance

4. Fish Benjie

5. The Assault on Glenraden

6. The Return of Harald Blacktooth

7. The Old Etonian Tramp

8. Sir Archie is Instructed in the Conduct of Life

9. Sir Archie Instructs his Countrymen

10. In which Crime is Added to Crime

11. Haripol – the Main Attack

12. Haripol – Transport

13. Haripol – Auxiliary Troops

14. Haripol – Wounded and Missing

15. Haripol – the Armistice

Epilogue

ONE

In which Three Gentlemen Confess their Ennui

The great doctor stood on the hearth-rug looking down at his friend who sprawled before him in an easy-chair. It was a hot day in early July, and the windows were closed and the blinds half-down to keep out the glare and the dust. The standing figure had bent shoulders, a massive clean-shaven face, and a keen interrogatory air, and might have passed his sixtieth birthday. He looked like a distinguished lawyer, who would soon leave his practice for the Bench. But it was the man in the chair who was the lawyer, a man who had left forty behind him, but was still on the pleasant side of fifty.

‘I tell you for the tenth time that there’s nothing the matter with you.’

‘And I tell you for the tenth time that I’m miserably ill.’

The doctor shrugged his shoulders. ‘Then it’s a mind diseased, to which I don’t propose to minister. What do you say is wrong?’

‘Simply what my housekeeper calls a “no-how” feeling.’

‘It’s clearly nothing physical. Your heart and lungs are sound. Your digestion’s as good as anybody’s can be in London in Midsummer. Your nerves – well, I’ve tried all the stock tests, and they appear to be normal.’

‘Oh, my nerves are all right,’ said the other wearily.

‘Your brain seems good enough, except for this dismal obsession that you are ill. I can find no earthly thing wrong, except that you’re stale.

1 comment