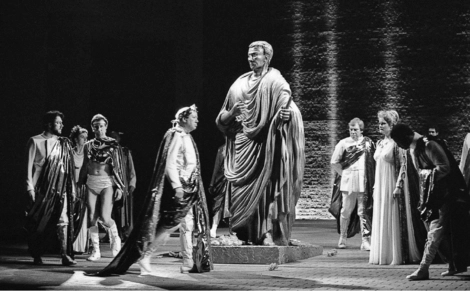

It subtly alters the texture and surfaces and manipulates space like a shaping force. This is important, because it underlines what seems to me Hands’s main insight into the play. Its first half is mostly bathed in the cold light of public politics. Caesar (David Waller) is an insufferable conviction politician who thrives on exposure. His is a harsh, imperious world: the space is defined by brutal columns of white light which might have been designed by Albert Speer.70

3. Terry Hands’s production in 1987 had a stripped-down stage and instead used lighting sculpturally. His was “a harsh, imperious world: the space is defined by brutal columns of white light.”

Clearly, there’s no alternative to Caesar, and the senators conspire in private darkness; at the end, Brutus and Cassius are isolated in black spaces of error, terror and division pierced by sinister shafts of purple light.71

David Thacker’s 1993 production at The Other Place was the first RSC production of Julius Caesar to dispense with Roman dress. He set his play in a very recognizable European world of late twentieth-century conflict:

1989 was a time of huge change in eastern European society. As a revolutionary play Julius Caesar sits happily in revolutionary times. We felt that the political schism in the Eastern Bloc which is so fresh in our minds would give the production dynamism and contemporary relevance … We agreed there was little to be gained from squeezing the play into a specifically Romanian, Russian or Czechoslovakian setting or by saying that Caesar is Gorbachev, Ceauşescu, Honecker. We were not wanting to create direct or specific parallels but rather to draw on the power of contemporary political change in order to demonstrate the seriousness and relevance of the issues addressed in the play. To be non-specific about a setting is not to be evasive or indecisive but to allow members of the audience to make other associations of dictatorship and the struggle for democracy for instance in South Africa or Latin America.

The potency of modern dress cannot be underestimated for an audience which might find Shakespeare’s verse alienating. Images of suited politicians and uniformed generals in contrast to a poorly dressed crowd have the immediacy and apparent veracity of a news story on television. The struggle for democracy encapsulated in Julius Caesar is sadly still going on.72

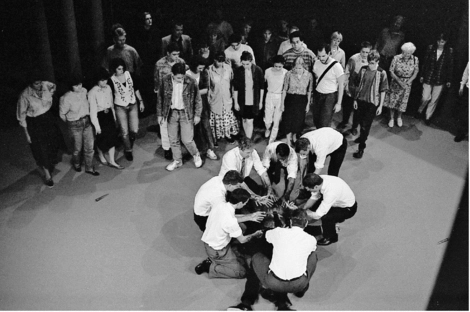

In order to hit home the contemporary experience and make the audience more directly involved with the action of the play, Thacker decided to stage the play as a promenade production. The audience stood around the actors, witnesses to the action at close proximity. One reviewer commented:

To find yourself standing a mere yard from the assassins as they roll up their shirt-sleeves and bathe their arms in Caesar’s blood is as nicely horrid as you can imagine.73

In an interview for the Independent, Thacker explained his choice:

This is a play about people manipulating or dealing with crowds … I thought it would be theatrically exciting to have people there on stage so they experience being in a large group of people hearing the speeches. I hope it might make them think “Would I believe this?” in a more concrete way than usual.74

4. David Thacker’s 1993 RSC production had a promenade audience: “To find yourself standing a mere yard from the assassins as they roll up their shirt-sleeves and bathe their arms in Caesar’s blood is as nicely horrid as you can imagine.”

A fine balance was reached in which the audience were not compelled to engage with the actors but were used as an integral part of the staging:

To call this production promenade is only a short hand to say there are no seats: this is not a conventional audience-stage relationship. A promenade performance usually means moving from area to area in a huge space so that the audience is literally taken on a journey. This production is, in reality, more “environmental.” The audience is in and of that environment, not only close to but also participating in the action: the human walls in which our drama is played.75

In creating a direct correlation between what people were witnessing on the television at home sitting on their sofa, and what they saw standing in the theater, Thacker took his audiences into a world disturbingly reminiscent of the Bosnian conflict. The battles took place amid the sound of machine-gun fire, and propagandists walked in among the audience and actors with video cameras filming the action. This method of staging gave the production an energy and excitement many others have lacked. Many praised the production’s contemporary directness:

Photos of David Sumner’s Caesar festoon the theatre walls, and then on comes the man himself, tracked by a video-camera as he saunters through the modern-day mob in his expensive Italian serge … The lynching of Cinna the poet might be the climax of an ugly riot on a London estate. Philippi might be happening in Bosnia tomorrow. This is not a Julius Caesar for those in search of subtlety; but for those who want action, it is a production to admire.76

The stage devices, which had proved effective in Thacker’s production, were picked up in David Farr’s touring production in 2004:

Stage managers double as performers, visibly pushing computer keys to make the neon lights fizz and flash for a Roman storm, then playing servants, then crouching down with follow-spots that irradiate Brutus’s face or video cameras that transpose public speeches to a screen behind an empty stage. Empty that is, except when battle occurs—and institutional chairs and tables are hurled about or used as barricades.77

Although the design had references to conflict in Eastern Europe, and especially civil conflict in Russia, the inferences reflected current feelings about the war in Iraq:

Together with designer Ti Green, he has created a loosely contemporary Rome that describes the confused world we live in at the moment, one in which people want their leaders to be strong and yet not arrogantly autocratic, and where a clear-cut objective—to remove a tyrant in the name of freedom—unleashes violent disorder. The mob—dressed in fashionable casuals—clamber up steel gantries, holler the name “Caesar” and unfurl banners onto which video images of the suited politician are projected.78

the programme is filled with references to Putin and Berlusconi … when Brutus urges the assassination of Caesar, even if “the quarrel will bear no colour for the thing he is,” we suddenly seem to be in the chilling world of pre-emptive regime-change.79

For Always I Am Caesar

Caesar’s weaknesses, and there are many, balance but do not cancel out his symbolic strength.80

Contrary to what many critics assume, Julius Caesar is not a play of two halves. The action is continuous and is often best when played without an interval. When a break is taken after the assassination scene, or the murder of Cinna the Poet, it can often kill the momentum of the preceding acts and give the play a disjointed feel. Directors are keen to establish a strong sense of Caesar’s influence and dominant spirit after the assassination by use of various stage devices. In 1968, director John Barton knew

that Caesar never ceases to rule. In death his presence governs the tragedy81 … In life, in the person of Brewster Mason, the dictator is physically dominating, not the husk we have had so often.

1 comment