I felt that the unifying element to the play was Julius Caesar—far from leaving the play, as soon as he is killed, his spirit lives on—no one stops talking about him. He returns in the second half to haunt Brutus, and in our production he appears at the very end as the revenging ghost stalking the battlefield, taking Brutus with him. One of the central questions that preoccupied Shakespeare and his contemporary audience was the nature of monarchy—at what point does monarchy become tyranny? Is it possible to rule without resorting to violence and suppression? Is assassination ever justified and does it produce change for the better? Julius Caesar reads like a political thriller, all the action of the first half is the tense lead-up to the assassination, and then the second half is the bloody aftermath. One man’s blood becomes a sea of blood.

Did you opt for an ancient setting or something to suggest more modern parallels?

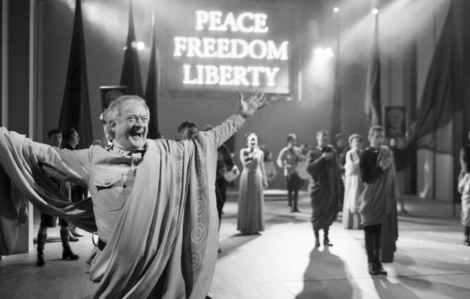

Hall: My production had a more contemporary setting. It had an aura of fascism about it. I took the slogan “Peace, Freedom and Liberty,” which is one of the slogans which comes up in the play, as the party’s slogan: that’s what Caesar stood for. We had a huge neon sign at the back that lit up during the opening procession and the climax saying “Peace, Freedom and Liberty.” There were dark uniforms and jackboots, but over the top of that there was the stencil of ancient Rome: people wore rather elegant togas so you could still feel the classical world on stage.

Farr: We had a strong modern setting. We had a clear idea in our heads, which we didn’t need the audience to fully understand in order to experience the story, but which we essentially created in our heads: a modern nation state in which a Putin-like leader was doing exactly this, was attempting to extend his role into a long-term presidential role. At the time we were doing it Putin was considering changing the constitution from a five-year presidential reign to a ten-year one. He didn’t do it in the end, but he was considering it and we were inspired by that. So we used a modern language and we explored the idea of a theater company invading an existing government space, a factory I suppose, in order to present a kind of guerrilla underground version of this play as a mode of protest. There was a whole Brechtian guerrilla theater quality. The audience weren’t in on that and we didn’t try and make it overt, it was a way in which to make the story clear and feel urgent and immediate. It is a short play and it has got an intense pace about it; it doesn’t have as much eccentricity as some of Shakespeare’s other plays, it just does exactly what is intended, like a thriller. I was making it for the regional tour and I had a strong desire to make it for what I perceived to be a young audience, or an audience that was new to Shakespeare, and I felt it was important to make, in a sophisticated way, the work feel urgent and contemporary.

6. Edward Hall’s contemporary setting, RSC 2001–02: “We had a huge neon sign at the back which lit up during the opening procession and the climax saying ‘Peace, Freedom and Liberty.’ There were dark uniforms and jackboots but over the top of that there was the stencil of ancient Rome.”

Bailey: I was immediately drawn to the primal brutal world that Shakespeare depicts in this play, but at the same time very conscious of its contemporary resonance. It describes a world where the decisions of a few powerful men affect the lives of hundreds and thousands—where the repercussions of these decisions end up in mass slaughter. It couldn’t be more relevant today. The belief system of this world is pre-Christian, based on the amoral activities of the gods dictated by signs and portents. A world of stunning creativity and unbelievable cruelty—and not so far from our post-Christian world, which has returned to an excessive and similar obsession with sex and violence.

Working with my designer Bill Dudley, our first instinct was to avoid any architectural representation of Rome on stage. We wanted to capture the atmosphere of violence and panic that is the backdrop to the play—and is the climate in which the assassination takes place. This led us to the use of film to suggest a Rome full of frightened people—an irrational, unstable world governed by portents and dreams. Our set was incredibly simple to look at, but hard to realize. A series of six gauzes which could move in parallel to each other, creating entrances between them or becoming one flat backdrop. Onto these gauzes we projected images of our cast duplicated to become a massive crowd. These films would echo the action on stage, lending every scene in the first half a sense of frenetic movement and panic, and in the second half capturing the vast military campaign.

Do audiences need to be familiar with the backstory/events leading up to the play before it begins?

Hall: No, I don’t think an audience should ever need to be familiar with any of that. I think it’s our job to deliver the play in such a way that somebody can walk in from a heavy day’s work, collapse in a seat, look up and get taken on a journey where they don’t have to have swallowed a book or a dictionary to understand what is going on.

Bailey: It’s a brilliantly written political thriller—a real page-turner. The play starts mid-crisis, at fever pitch and continues at that pace, never letting up. Shakespeare is brilliant at encapsulating what has gone on before with an amazing brevity and speed. I think the challenge to the stage director is to tell the story in a way that illuminates the text. All the information you need is there in Shakespeare’s words, so it’s up to the production to excavate it.

1 comment