There is no documentary proof, for example, that Othello is not as early as Romeo and Juliet, but one feels that Othello is a later, more mature work, and because the first record of its performance is 1604, one is glad enough to set its composition at that date and not push it back into Shakespeare’s early years. (Romeo and Juliet was first published in 1597, but evidence suggests that it was written a little earlier.) The following chronology, then, is indebted not only to facts but also to informed guesswork and sensitivity. The dates, necessarily imprecise for some works, indicate something like a scholarly consensus concerning the time of original composition. Some plays show evidence of later revision.

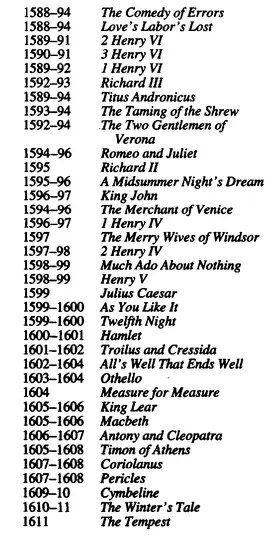

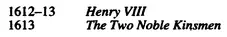

Plays. The first collected edition of Shakespeare, published in 1623, included thirty-six plays. These are all accepted as Shakespeare‘s, though for one of them, Henry VIII, he is thought to have had a collaborator. A thirty-seventh play, Pericles, published in 1609 and attributed to Shakespeare on the title page, is also widely accepted as being partly by Shakespeare even though it is not included in the 1623 volume. Still another play not in the 1623 volume, The Two Noble Kinsmen, was first published in 1634, with a title page attributing it to John Fletcher and Shakespeare. Probably most students of the subject now believe that Shakespeare did indeed have a hand in it. Of the remaining plays attributed at one time or another to Shakespeare, only one, Edward III, anonymously published in 1596, is now regarded by some scholars as a serious candidate. The prevailing opinion, however, is that this rather simple-minded play is not Shakespeare’s; at most he may have revised some passages, chiefly scenes with the Countess of Salisbury. We include The Two Noble Kinsmen but do not include Edward III in the following list.

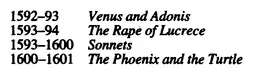

Poems. In 1989 Donald W. Foster published a book in which he argued that “A Funeral Elegy for Master William Peter,” published in 1612, ascribed only to the initials W.S., may be by Shakespeare. Foster later published an article in a scholarly journal, PMLA 111 (1996), in which he asserted the claim more positively. The evidence begins with the initials, and includes the fact that the publisher and the printer of the elegy had published Shakespeare’s Sonnets in 1609. But such facts add up to rather little, especially because no one has found any connection between Shakespeare and William Peter (an Oxford graduate about whom little is known, who was murdered at the age of twenty-nine). The argument is based chiefly on statistical examinations of word patterns, which are said to correlate with Shakespeare’s known work. Despite such correlations, however, many readers feel that the poem does not sound like Shakespeare. True, Shakespeare has a great range of styles, but his work is consistently imaginative and interesting. Many readers find neither of these qualities in “A Funeral Elegy.”

Shakespeare’s English

1. Spelling and Pronunciation. From the philologist’s point of view, Shakespeare’s English is modern English. It requires footnotes, but the inexperienced reader can comprehend substantial passages with very little help, whereas for the same reader Chaucer’s Middle English is a foreign language. By the beginning of the fifteenth century the chief grammatical changes in English had taken place, and the final unaccented -e of Middle English had been lost (though it survives even today in spelling, as in name); during the fifteenth century the dialect of London, the commercial and political center, gradually displaced the provincial dialects, at least in writing; by the end of the century, printing had helped to regularize and stabilize the language, especially spelling. Elizabethan spelling may seem erratic to us (there were dozens of spellings of Shakespeare, and a simple word like been was also spelled beene and bin), but it had much in common with our spelling. Elizabethan spelling was conservative in that for the most part it reflected an older pronunciation (Middle English) rather than the sound of the language as it was then spoken, just as our spelling continues to reflect medieval pronunciation—most obviously in the now silent but formerly pronounced letters in a word such as knight. Elizabethan pronunciation, though not identical with ours, was much closer to ours than to that of the Middle Ages. Incidentally, though no one can be certain about what Elizabethan English sounded like, specialists tend to believe it was rather like the speech of a modem stage Irishman (time apparently was pronounced toime, old pronounced awld, day pronounced die, and join pronounced jine) and not at all like the Oxford speech that most of us think it was.

An awareness of the difference between our pronunciation and Shakespeare’s is crucial in three areas—in accent, or number of syllables (many metrically regular lines may look irregular to us); in rhymes (which may not look like rhymes); and in puns (which may not look like puns). Examples will be useful. Some words that were at least on occasion stressed differently from today are aspèct, còmplete, fòrlorn, revènue, and sepùlcher. Words that sometimes had an additional syllable are emp[e]ress, Hen[e]ry, mon[e]th, and villain (three syllables, vil-lay-in). An additional syllable is often found in possessives, like moon’s (pronounced moones) and in words ending in -tion or -sion. Words that had one less syllable than they now have are needle (pronounced neel) and violet (pronounced vilet). Among rhymes now lost are one with loan, love with prove, beast with jest, eat with great. (In reading, trust your sense of metrics and your ear, more than your eye.) An example of a pun that has become obliterated by a change in pronunciation is Falstaff’s reply to Prince Hal’s “Come, tell us your reason” in 1 Henry IV: “Give you a reason on compulsion? If reasons were as plentiful as blackberries, I would give no man a reason upon compulsion, I” (2.4.237-40). The ea in reason was pronounced rather like a long a, like the ai in raisin, hence the comparison with blackberries.

Puns are not merely attempts to be funny; like metaphors they often involve bringing into a meaningful relationship areas of experience normally seen as remote.

1 comment