He knew that his father no longer went to work. He knew, too, that his father and mother never spoke of it before him—that in their rough, kind way they had tried to keep their burdens of living from bearing also on his young shoulders.

Though his brain told him these things, his heart still cried for Lassie. But he silenced it. He stood steadily and then asked one question.

“Couldn’t we buy her back some day, Mother?”

“Now, Joe, she was a very valuable dog and she’s worth too much for us. But we’ll get another dog some day. Just wait. Times might pick up, and then we’ll get another pup. Wouldn’t ye like that?”

Joe Carraclough bent his head and shook it slowly. His voice was only a whisper.

“I don’t ever want another dog. Never! I only want—Lassie!”

CHAPTER THREE

An Evil-tempered Old Man

The Duke of Rudling stood by a rhododendron hedge and glared about him. He lifted his voice again.

“Hynes!” he roared. “Hynes! Where has that chap got to? Hynes!”

At that moment, with his face red and his shock of white hair disordered, the Duke looked like what he was reputed to be: the worst-tempered old man in all the three Ridings of Yorkshire.

Whether or not he deserved this reputation, it would seem sufficient to say that his words and actions earned it.

Perhaps it was partly due to the fact that the Duke was exceedingly deaf, which caused him to speak to everyone as if he were commanding a brigade of infantry on parade, as indeed he had done, many years ago. He had also a habit of carrying a big blackthorn walking stick, which he always waved wildly in the air in order to give emphasis to his already too emphatic words. And finally, his bad temper came from his impatience with the world.

For the Duke had one firm belief: which was that the world was going, as he phrased it, “to pot.” Nothing ever was as good these days as it had been when he was a young man. Horses could not run so fast, young men were not so brave and dashing, women were not so pretty, flowers did not grow so well, and as for dogs, if there were any decent ones left in the world, it was because they were in his own kennels.

The people could not even speak the King’s English these days as they could when he was a young man, according to the Duke. He was firmly of the opinion that the reason he could not hear properly was not because he was deaf, but because people nowadays had got into the pernicious habit of mumbling and snipping their words instead of saying them plainly as they did when he was a young man.

And, as for the younger generation! The Duke could—and often would—lecture for hours on the worthlessness of everyone born in the twentieth century.

This last was curious, for of all his relatives, the only one the Duke could stand (and who could also stand the Duke, it seemed) was the youngest member of his family, his twelve-year-old granddaughter, Priscilla.

It was Priscilla who came to his rescue now as he stood, waving his stick and shouting, beside the rhododendron hedge.

Dodging a wild swish of his stick, she reached over and pulled the pocket of his tweed Norfolk coat. He turned with bristling moustaches.

“Oh, it’s you!” he roared. “It’s a wonder somebody finally came. Don’t know what the world’s coming to. Servants no good! Everybody too deaf to hear! Country’s going to pot!”

“Nonsense,” said Priscilla.

She was indeed a very self-contained and composed young lady. From her continued association with her grandfather, she had grown to consider both of them as equals—either as old children or as very young grownups.

“What’s that?” the Duke roared, looking down at her. “Speak up! Don’t mumble!”

Priscilla pulled his head down so that she could speak directly into his ear.

“I said, Nonsense!” she shouted.

“Nonsense?” roared the Duke.

He stared down at her, then broke into a roar of laughter. He had a curious way of reasoning about Priscilla. He was convinced that if Priscilla had pluck enough to answer him back, she must have inherited it from him.

So the Duke felt in a much better temper as he looked down at his granddaughter. He flourished his long white moustaches, which were much grander and finer than the kind of moustaches that men manage to grow these days.

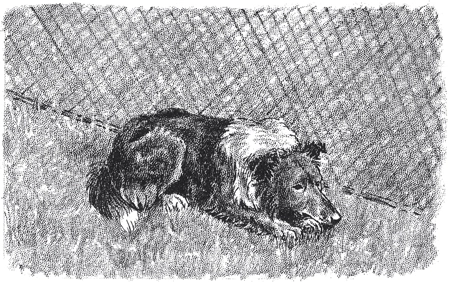

“Ah, glad you turned up,” the Duke boomed. “I want you to see a new dog. She’s marvellous! Beautiful! Finest collie I ever laid my eyes on.”

“She isn’t so good as the ones they had in the old days, is she?” Priscilla asked.

“Don’t mumble,” roared the Duke. “Can’t hear a word you say.”

He had heard perfectly well, but had decided to ignore it.

“Knew I’d get her,” the Duke continued. “Been after her for three years now.”

“Three years!” echoed Priscilla. She knew that was what her grandfather wanted her to say.

“Yes, three years.

1 comment