His followers have certainly refreshed and expanded his message, but Whitman’s own words have such powerful and continuous relevance that he seems to address us face to face, rather than talk at our backs. Deliberately leaving off the end punctuation at the close of the 1855 edition of “Song of Myself ” (p. 91), he remains ever a step ahead:

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop some where waiting for you

Karen Karbiener received her Ph.D. in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in 2001 and teaches at New York University. A scholar of Romanticism and radical cultural legacies, she is the general editor of the forthcoming Encyclopedia of American Counterculture (M.E. Sharpe, 2006). She is currently curating an exhibit for the 150th anniversary of Leaves of Grass, entitled “Walt Whitman and the Promise of America, 1855-2005.” She lives in and loves her hometown, New York City.

Leaves of Grass

Brooklyn, New York : 1855.

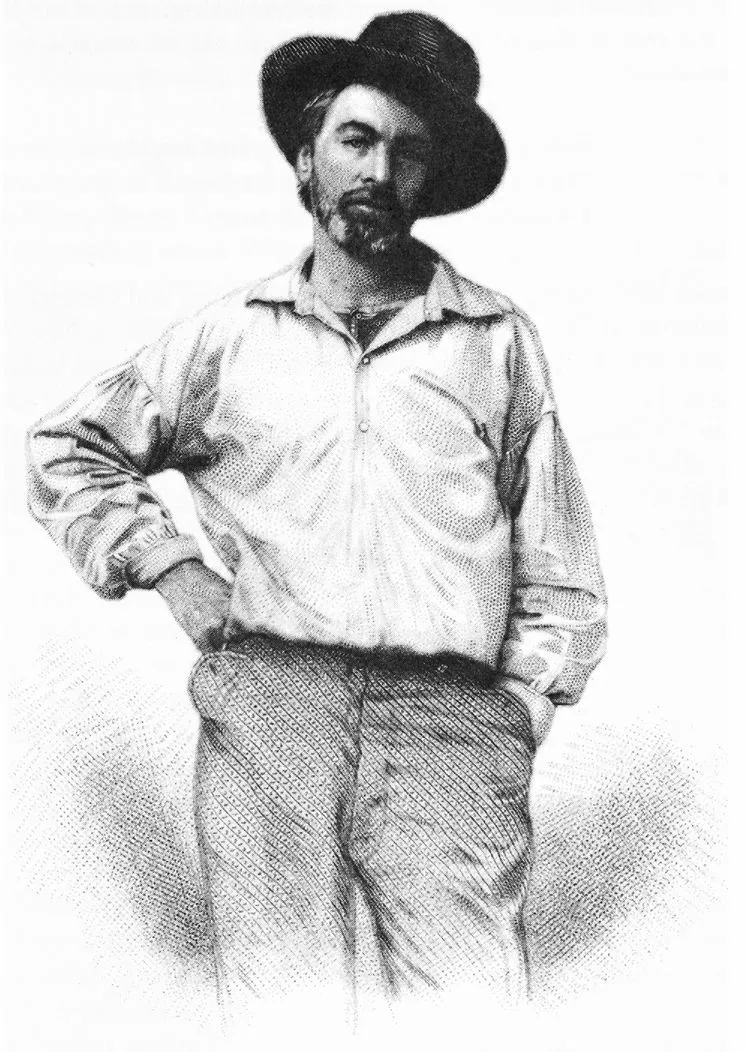

“Christ likeness”—About 35 years old, c.1854, possibly taken by

Gabriel Harrison, although the photographer and place of sitting are

unknown. Courtesy of the Bayley-Whitman Collection of Ohio Wesleyan

University, Delaware, Ohio, and the Walt Whitman Birthplace Association,

Huntington, New York. Saunders #5.

INTRODUCTION TO FIRST EDITION

Walt Whitman was a poet of great first inspiration. That fact might come as a surprise to anyone who knows how many times Whitman revised and expanded Leaves of Grass over his lifetime. But the twelve “core poems” of the First Edition are arguably Whitman at his best. This is Whitman in the raw: His stance is defiant and provocative, his vision all-encompassing, his voice uninhibited, his demands radical. The passion and energy of his message and the rushing flow of the unregulated lines still feel revolutionary, 150 years after the book’s publication. The appearance of the First Edition even heralded a new way of presenting poetry: Neither cover nor title page gave an indication of an author’s name. Instead, across from the title page appeared the image of a man who might have easily been the reader. Everything about this book signaled the author’s desire, and ability, to be an American literary pioneer. Indeed, Whitman had overseen this project from his first vision for it, to composition, to typesetting, to production and distribution; he even wrote anonymous reviews of Leaves of Grass.

“An American Bard at last!” Whitman proclaimed of himself in a self-review published in 1855. Whitman wrote two such reviews that year to offer explanations of his unusual project and stir up interest in Leaves of Grass. According to Florence Rome Garrett, granddaughter of the printers who helped Whitman produce the First Edition, “practically none sold.” The public’s ambivalence may have been fostered in part by the lack of an author’s name-not that placing “Walt Whitman” on the cover would have done much to encourage sales. At best, fellow Brooklynites might have recognized Whitman as a writer and sometime editor of the city’s more liberal newspapers; others might have remembered that he and his father had both worked as carpenters, and that while Whitman Senior’s weakness may have been alcohol, Walt’s was laziness. The name “Walt Whitman” had rarely been associated with poetry before 1855. The “Additional Poems” section of this Barnes and Noble Classics edition contains the only poetic efforts Whitman is known to have published before the arrival of Leaves of Grass in 1855. Even the single poem in the 1855 edition that had previously been published—“Resurgemus,” published in the New York Tribune on June 21, 1850—underwent radical transformation before becoming the eighth of the twelve poems. The interest in reading through the first edition of Leaves of Grass, then, derives not only from looking at it as a point of departure for later editions, but also from marveling at this remarkable, as-yet mysterious first effort.

—Karen Karbiener

[PREFACE1]

AMERICA does not repel the past or what it has produced under its forms or amid other politics or the idea of castes or the old religions ... accepts the lesson with calmness ... is not so impatient as has been supposed that the slough still sticks to opinions and manners and literature while the life which served its requirements has passed into the new life of the new forms ... perceives that the corpse is slowly borne from the eating and sleeping rooms of the house ... perceives that it waits a little while in the door ... that it was fittest for its days ... that its action has descended to the stalwart and wellshaped heir who approaches ...

1 comment