Likewise, Iqbal Meer has devoted many hours to watching over the business aspects of the book. I am grateful to my editor, William Phillips of Little, Brown, who has guided this project from early 1990 on, and edited the text, and to his colleagues Jordan Pavlin, Steve Schneider, Mike Mattil, and Donna Peterson. I would also like to thank Professor Gail Gerhart for her factual review of the manuscript.

Part One

A COUNTRY CHILDHOOD

1

APART FROM LIFE, a strong constitution, and an abiding connection to the Thembu royal house, the only thing my father bestowed upon me at birth was a name, Rolihlahla. In Xhosa, Rolihlahla literally means “pulling the branch of a tree,” but its colloquial meaning more accurately would be “troublemaker.” I do not believe that names are destiny or that my father somehow divined my future, but in later years, friends and relatives would ascribe to my birth name the many storms I have both caused and weathered. My more familiar English or Christian name was not given to me until my first day of school. But I am getting ahead of myself.

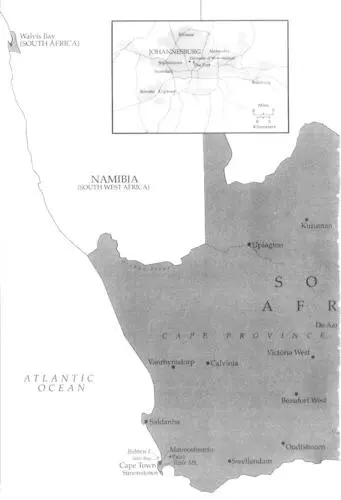

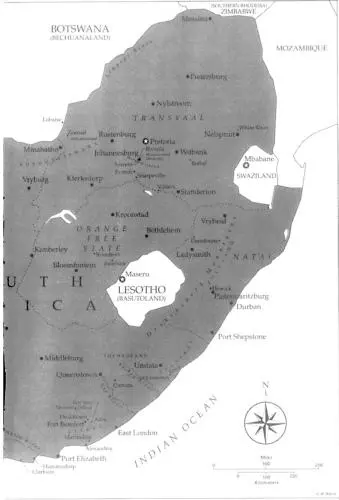

I was born on the eighteenth of July, 1918, at Mvezo, a tiny village on the banks of the Mbashe River in the district of Umtata, the capital of the Transkei. The year of my birth marked the end of the Great War; the outbreak of an influenza epidemic that killed millions throughout the world; and the visit of a delegation of the African National Congress to the Versailles peace conference to voice the grievances of the African people of South Africa. Mvezo, however, was a place apart, a tiny precinct removed from the world of great events, where life was lived much as it had been for hundreds of years.

The Transkei is eight hundred miles east of Cape Town, five hundred fifty miles south of Johannesburg, and lies between the Kei River and the Natal border, between the rugged Drakensberg mountains to the north and the blue waters of the Indian Ocean to the east. It is a beautiful country of rolling hills, fertile valleys, and a thousand rivers and streams, which keep the landscape green even in winter. The Transkei used to be one of the largest territorial divisions within South Africa, covering an area the size of Switzerland, with a population of about three and a half million Xhosas and a tiny minority of Basothos and whites. It is home to the Thembu people, who are part of the Xhosa nation, of which I am a member.

My father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, was a chief by both blood and custom. He was confirmed as chief of Mvezo by the king of the Thembu tribe, but under British rule, his selection had to be ratified by the government, which in Mvezo took the form of the local magistrate. As a government-appointed chief, he was eligible for a stipend as well as a portion of the fees the government levied on the community for vaccination of livestock and communal grazing land. Although the role of chief was a venerable and esteemed one, it had, even seventy-five years ago, become debased by the control of an unsympathetic white government.

The Thembu tribe reaches back for twenty generations to King Zwide. According to tradition, the Thembu people lived in the foothills of the Drakensberg mountains and migrated toward the coast in the sixteenth century, where they were incorporated into the Xhosa nation. The Xhosa are part of the Nguni people who have lived, hunted, and fished in the rich and temperate southeastern region of South Africa, between the great interior plateau to the north and the Indian Ocean to the south, since at least the eleventh century. The Nguni can be divided into a northern group — the Zulu and the Swazi people — and a southern group, which is made up of amaBaca, amaBomyana, amaGcaleka, amaMfengu, amaMpodomis, amaMpondo, abeSotho, and abeThembu, and together they comprise the Xhosa nation.

The Xhosa are a proud and patrilineal people with an expressive and euphonious language and an abiding belief in the importance of laws, education, and courtesy. Xhosa society was a balanced and harmonious social order in which every individual knew his or her place. Each Xhosa belongs to a clan that traces its descent back to a specific forefather. I am a member of the Madiba clan, named after a Thembu chief who ruled in the Transkei in the eighteenth century. I am often addressed as Madiba, my clan name, a term of respect.

Ngubengcuka, one of the greatest monarchs, who united the Thembu tribe, died in 1832. As was the custom, he had wives from the principal royal houses: the Great House, from which the heir is selected, the Right Hand House, and the Ixhiba, a minor house that is referred to by some as the Left Hand House. It was the task of the sons of the Ixhiba or Left Hand House to settle royal disputes. Mthikrakra, the eldest son of the Great House, succeeded Ngubengcuka and amongst his sons were Ngangelizwe and Matanzima. Sabata, who ruled the Thembu from 1954, was the grandson of Ngangelizwe and a senior to Kalzer Daliwonga, better known as K. D. Matanzima, the former chief minister of the Transkei — my nephew, by law and custom — who was a descendant of Matanzima. The eldest son of the Ixhiba house was Simakade, whose younger brother was Mandela, my grandfather.

Although over the decades there have been many stories that I was in the line of succession to the Thembu throne, the simple genealogy I have just outlined exposes those tales as a myth. Although I was a member of the royal household, I was not among the privileged few who were trained for rule. Instead, as a descendant of the Ixhiba house, I was groomed, like my father before me, to counsel the rulers of the tribe.

My father was a tall, dark-skinned man with a straight and stately posture, which I like to think I inherited.

1 comment