Mary Stuart

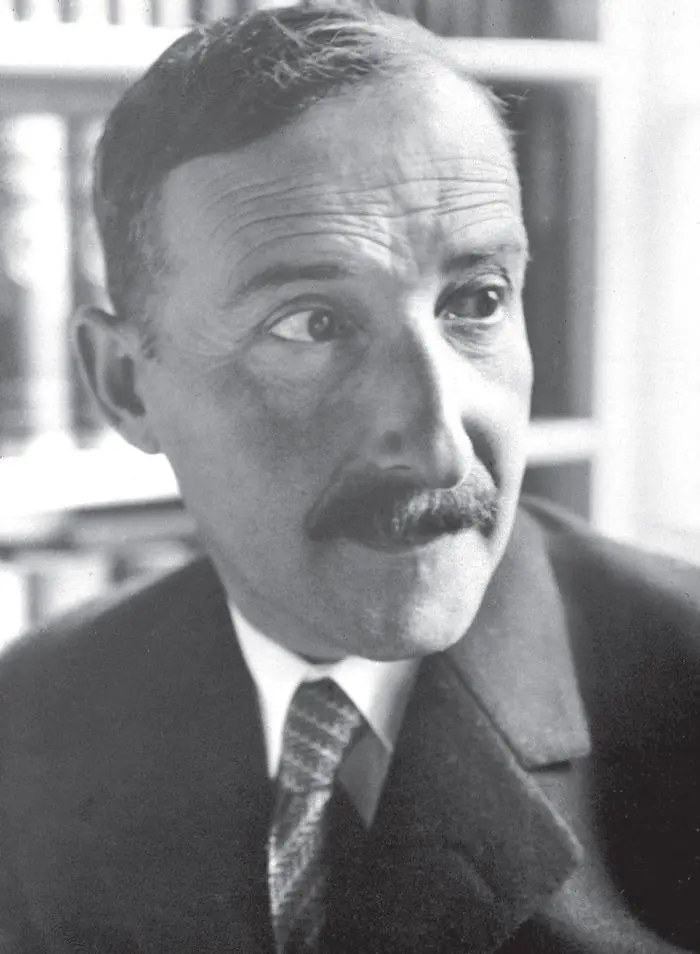

STEFAN ZWEIG

MARY STUART

Translated from the German

by Eden and Cedar Paul

PUSHKIN PRESS

LONDON

Contents

Title Page

Queen in the Cradle (1542–8)

Youth in France (1548–59)

Queen, Widow, and Still Queen (1560–1)

Return to Scotland (August 1561)

The Stone Begins to Roll (1561–3)

Political Marriage Mart (1563–5)

Passion Decides (1565)

The Fatal Night in Holyrood (9th March 1566)

Traitors Betrayed (March to June 1566)

A Terrible Entanglement (July to Christmas 1566)

The Tragedy of a Passion (1566–7)

The Path to Murder (22nd January to 9th February 1567)

Quos Deus Perdere Vult …(February to April 1567)

A Blind Alley (April to June 1567)

Deposition (Summer 1567)

Farewell to Freedom (Summer 1567 to Summer 1568)

Weaving a Net (16th May to 28th June 1568)

The Net Closes Round Her (July 1568 to January 1569)

Years Spent in the Shadows (1569–84)

War to the Knife (1584–5)

“The Matter Must Come to an End” (September 1585 to August 1586)

Elizabeth against Elizabeth (August 1586 to February 1587)

“En Ma Fin Est Mon Commencement” (8th February 1587)

Aftermath (1587–1603)

Other Stefan Zweig titles published by Pushkin Press

Copyright

Chapter One

(1542–8)

MARY STUART WAS ONLY SIX DAYS OLD when she became Queen of Scotland, thus obeying in spite of herself what appears to have been the law of her life—to receive too soon and without conscious joy what Fate had to give her. On the same dreary December day in 1542 that Mary was born at Linlithgow Castle, her father, James V, was breathing his last in the royal palace at Falkland, little more than twenty miles away. Although he had hardly reached the age of thirty-one, he was broken on the wheel of life, tired of his crown and wearied of perpetual warfare. He had proved a brave and chivalrous man, fundamentally cheerful by disposition, a passionate friend of the arts and of women, trusted by his people. Many a time would he put on a disguise in order to participate unrecognised at village merry-makings, dancing and joking with the peasant folk. But this unlucky scion of an unlucky house had been born into a wild epoch and within the borders of an intractable land. From the outset he seemed foredoomed to a tragical destiny.

A self-willed and inconsiderate neighbour, Henry VIII, tried to force the Scottish King to introduce the Reformation into the northern realm. But James V remained a faithful son of the old Church. The lords and nobles gleefully took every opportunity to create trouble for their sovereign, stirring up contention and misunderstanding, and involving the studious and pacific James in further turmoil and war. Four years earlier, when he was suing for Mary of Guise’s hand in marriage, he made clear in a letter to the lady how heavy a task it was to act as King to the rebellious and rapacious clans. “Madam,” he wrote in this moving epistle (penned in French),

I am no more than seven-and-twenty years of age, and life is already crushing me as heavily as does my crown … An orphan from my earliest childhood, I fell a prey to ambitious noblemen; the powerful House of Douglas kept me prisoner for many years, and I have come to hate the name of my persecutors and any references to the sad days of my captivity. Archibald, Earl of Angus, George his brother, together with their exiled relatives, are untiring in their endeavours to rouse the King of England against me and mine. There is not a nobleman in my realm who has not been seduced from his allegiance by promises and bribes. Even my person is not safe; there is no guarantee that my wishes will be carried out, or that existing laws will be obeyed. All these things alarm me, madam, and I expect to receive from you both strength and counsel. I have no money, save that which comes to me from France’s generosity and through the thrift of my wealthier clergy; and it is with these scanty funds that I try to adorn my palaces, maintain my fortresses and build my ships. Unfortunately, my barons look upon a king who would act the king in very deed as an insufferable rival. In spite of the friendship shown me by the King of France, in spite of the support I receive from his armies, in spite of the attachment of my people to their monarch, I fear that I shall never be able to achieve a decisive victory over my unruly nobles. I would fain put every obstacle out of the path in order to bring justice and tranquillity to my people. Peradventure I might achieve this aim if my nobles were the only impediment. But the King of England never wearies of sowing discord between them and me; and the heresies he has introduced into the land are not only devouring my people as a whole, but have penetrated even into ecclesiastical circles. My power, as did that of my ancestors, rests solely upon the burgesses of my towns and upon the fidelity of my clergy, and I cannot but ask myself whether this power will long endure …

All the disasters foretold by the King in this letter took place, and even worse things befell the writer. The two sons Mary of Guise brought into the world died in the cradle, so that James, in the flower of his manhood, had no heir growing up beside him, an heir who should relieve him of the crown which, as the years passed, pressed more heavily on his brow. In despite of his own will and better judgement, he was pressed by his nobles to enter the field against England, a mighty enemy, only to be deserted by them in the eleventh hour. At Solway Moss, Scotland lost not only the battle but likewise her honour. Forsaken by the chieftains of the clans, the troops hardly put up even the semblance of a fight, but ran leaderless hither and thither. James, too, a man usually so acutely aware of his knightly duty, when the decisive hour came was no longer in a position to strike down the hereditary foe, for he was already wounded unto death. They bore him away, feverish and weary, and laid him to bed in his palace at Falkland. He had had his fill of the senseless struggle and of a life which had become nothing but a burden to him.

Mist wreaths darkened the window panes on 9th December 1542, when there came a messenger knocking at the door. He announced to the sick King that a daughter had been born to the House of Stuart—an heiress to the throne.

1 comment