The marriage of Beatrice and Benedick turns on the ability of their peers to trick them out of their self-conscious role-playing. It is of interest to note that the latter pair’s willingness to surrender to love and marriage takes place while Hero’s virtue is still under a cloud as far as Claudio is concerned, and therefore at a moment when their previous bantering would be inappropriate. It is equally important to note that both Beatrice and Benedick, if somewhat subdued, actually bring alive again, at the play’s end, something of the ambiguity toward love that they had had from the beginning of the play.

Beatrice’s final words are not those of a Rosalind or a Viola:

I yield upon great persuasion, and partly to save your life, for I was told you were in a consumption.

(5.4.95-96)

Benedick’s penultimate comments are addressed not to Beatrice, but rather to Don Pedro. And Benedick insists upon being as ambiguous about his feelings, now that he had agreed to conform to marriage, as he had been earlier, when he could only exclaim against it. He insists to Don Pedro that “since I do purpose to marry, I will think nothing to any purpose that the world can say against it” (104-6). He concludes that Don Pedro himself had better marry in order that he too may join the gay company of cuckolds-to-be:

get thee a wife, get thee a wife! There is no staff more reverend than one tipped with hom. (122-24)

In Romeo and Juliet, written about four years before Much Ado, Shakespeare had dramatized the lyric, fragile love of very young people not yet wise enough to yield to the social realities—and therefore broken by them. He had presented their love as a highly perishable commodity, one as subject to accident as to time. It is not only Romeo and Juliet, but we, as audience, who acquiesce in their deaths because we are fully aware that in “reality” there can only be either slow dilution or abrupt extinction of such flower-like love. In Twelfth Night, written probably a year or so later than Much Ado, we are kept within the elegant, golden confines of courtly, aristocratic romance—a place full of music and of bodily forms (to borrow from Yeats) “of hammered gold and gold enameling,” set singing to keep some “drowsy Emperor awake.”

The kind of love encompassed by the dialogue of Much Ado, and by its two sets of lovers, is love in the social world. This comedy, indeed, is a highly novel one for Shakespeare to have written. The play ends with its characters and the audience accepting the two marriages that have been in the making from its beginning. But the power of the comedy lies not in our accepting the fragility of youthful passion or in our surrender to idyllic romance. Rather, Much Ado, by all its strategies of language and characterization, moves so close to reality that it cannot reach a denouement in which the simply understood mood or attitude of Romeo and Juliet or of Twelfth Night reaches final focus.

The essential uniqueness of Much Ado as a comedy, and its fascination, lies in the fact that it invokes our awareness of the complicated relationship between the indeterminate nature of private feeling and the simplicities of the decorous behavior which is supposed to embody such feeling. That is to say, Much Ado dramatizes sex, love, and marriage in close imitation of their complexity in actuality. This play, of course, is far too stylized to be “real,” and it keeps us comically insulated from too deep involvement with its characters and its substance. The play’s final moment of balance, of standing still, then, is necessarily somewhat different from that of the Shakespearean romances where a long ritual of wooing comes to a ritualized conclusion. In Much Ado we are given, in its last scene, the dramatic illusion that the pair of marriages has been created by the volition of the characters themselves. They seem to be marrying out of their own desire to find, if only momentarily, a way of being at peace with themselves and with each other.

—DAVID L. STEVENSON

Hunter College

Much adoe about Nothing.

Enter Leonato governour of Meffina, Innogen bis wife, Here

his daughter, and Beatrice bis neece, with a

messenger.

Leonato.

I Learne in this letter, that don Peter of Arragon comes this night to Meffina.

Mess. He is very neare by this,he was not three leagues off when I left him.

Leona. How many gentlemen have you loft in this action?

Mess. But few of any fort, and none of name.

Leons. A victory is twice it felfe, when the atchiuer brings home ful numbers: I find here,that don Peter hath beftowed much honour on a yong Florentine called Claudio.

Mess. Much deferu don his part, and equally remembred by don Pedro he hath borne himfelfe beyond the promife of his age, doing in the figure of a lamb, the feats of a lion he hath indeed better bettred expectation then you must expect of me to tell you how.

Leo. He hath an vnckie here in Messina will be very much glad of it.

Mess. I have already delivered him letters, and there ap peares much joy in him, even to much, that ioy could not fhew it felfe modeft enough, without a badge of bitternesse.

Leo. Did he breake out into teares?

Mess. In great measure.

A 2 Leo.

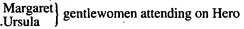

First page of text from the Quarto of 1600. Notice that in the first stage direction, the Governor of Messina is said to be accompanied by “Innogen his wife.” Apparently when Shakespeare began writing the scene, he thought he would include this character, but in fact she appears nowhere in the play.

Much Ado About Nothing

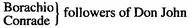

[Dramatis Personae

Don Pedro, Prince of Aragon

Don John, his bastard brother

Claudio, a young lord of Florence

Benedick, a young lord of Padua

Leonato, Governor of Messina

Antonio, an old man, his brother

Balthasar, attendant on Don Pedro

Friar Francis

Dogberry, a constable

Verges, a headborough

A Sexton

A Boy

Hero, daughter to Leonato

Beatrice, niece to Leonato

Messengers, Watch, Attendants, &c.

Scene: Messina]

Much Ado About Nothing

[ACT 1

Scene I.

1 comment