In 2 Henry IV, when Feeble is conscripted, he stoically says, “I care not. A man can die but once. We owe God a death” (3.2.242-43), punning on debt, which was the way death was pronounced. Here an enormously significant fact of life is put into simple commercial imagery, suggesting its commonplace quality. Shakespeare used the same pun earlier in 1 Henry IV, when Prince Hal says to Falstaff, “Why, thou owest God a death,” and Falstaff replies, “‘Tis not due yet: I would be loath to pay him before his day. What need I be so forward with him that calls not on me?” (5.1.126-29).

Sometimes the puns reveal a delightful playfulness; sometimes they reveal aggressiveness, as when, replying to Claudius’s “But now, my cousin Hamlet, and my son,” Hamlet says, “A little more than kin, and less than kind!” (1.2.64-65). These are Hamlet’s first words in the play, and we already hear him warring verbally against Claudius. Hamlet’s “less than kind” probably means (1) Hamlet is not of Claudius’s family or nature, kind having the sense it still has in our word mankind; (2) Hamlet is not kindly (affectionately) disposed toward Claudius; (3) Claudius is not naturally (but rather unnaturally, in a legal sense incestu ously) Hamlet’s father. The puns evidently were not put in as sops to the groundlings; they are an important way of communicating a complex meaning.

2. Vocabulary. A conspicuous difficulty in reading Shakespeare is rooted in the fact that some of his words are no longer in common use—for example, words concerned with armor, astrology, clothing, coinage, hawking, horsemanship, law, medicine, sailing, and war. Shakespeare had a large vocabulary—something near thirty thousand words—but it was not so much a vocabulary of big words as a vocabulary drawn from a wide range of life, and it is partly his ability to call upon a great body of concrete language that gives his plays the sense of being in close contact with life. When the right word did not already exist, he made it up. Among words thought to be his coinages are accommodation, all-knowing, amazement, bare-faced, countless, dexterously, dislocate, dwindle, fancy-free, frugal, indistinguishable, lackluster, laughable, overawe, premeditated, sea change, star-crossed. Among those that have not survived are the verb convive, meaning to feast together, and smilet, a little smile.

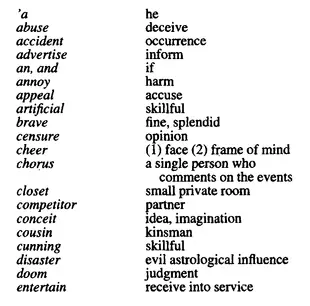

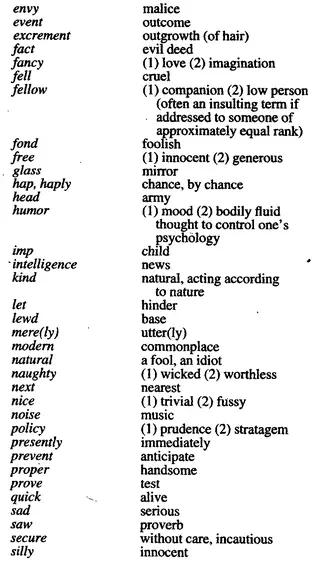

Less overtly troublesome than the technical words but more treacherous are the words that seem readily intelligible to us but whose Elizabethan meanings differ from their modem ones. When Horatio describes the Ghost as an “erring spirit,” he is saying not that the ghost has sinned or made an error but that it is wandering. Here is a short list of some of the most common words in Shakespeare’s plays that often (but not always) have a meaning other than their most usual modem meaning:

All glosses, of course, are mere approximations; sometimes one of Shakespeare’s words may hover between an older meaning and a modem one, and as we have seen, his words often have multiple meanings.

3. Grammar. A few matters of grammar may be surveyed, though it should be noted at the outset that Shakespeare sometimes made up his own grammar. As E.A. Abbott says in A Shakespearian Grammar, “Almost any part of speech can be used as any other part of speech”: a noun as a verb (“he childed as I fathered”); a verb as a noun (“She hath made compare”); or an adverb as an adjective (“a seldom pleasure”). There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of such instances in the plays, many of which at first glance would not seem at all irregular and would trouble only a pedant. Here are a few broad matters.

Nouns: The Elizabethans thought the -s genitive ending for nouns (as in man’s) derived from his; thus the line “ ‘gainst the count his galleys I did some service,” for “the count’s galleys.”

Adjectives: By Shakespeare’s time adjectives had lost the endings that once indicated gender, number, and case. About the only difference between Shakespeare’s adjectives and ours is the use of the now redundant more or most with the comparative (“some more fitter place”) or superlative (“This was the most unkindest cut of all”). Like double comparatives and double superlatives, double negatives were acceptable; Mercutio “will not budge for no man’s pleasure.”

Pronouns: The greatest change was in pronouns. In Middle English thou, thy, and thee were used among familiars and in speaking to children and inferiors; ye, your, and you were used in speaking to superiors (servants to masters, nobles to the king) or to equals with whom the speaker was not familiar. Increasingly the “polite” forms were used in all direct address, regardless of rank, and the accusative you displaced the nominative ye. Shakespeare sometimes uses ye instead of you, but even in Shakespeare’s day ye was archaic, and it occurs mostly in rhetorical appeals.

Thou, thy, and thee were not completely displaced, however, and Shakespeare occasionally makes significant use of them, sometimes to connote familiarity or intimacy and sometimes to connote contempt. In Twelfth Night Sir Toby advises Sir Andrew to insult Cesario by addressing him as thou: “If thou thou‘st him some thrice, it shall not be amiss” (3.2.46-47). In Othello when Brabantio is addressing an unidentified voice in the dark he says, “What are you?” (1.1.91), but when the voice identifies itself as the foolish suitor Roderigo, Brabantio uses the contemptuous form, saying, “I have charged thee not to haunt about my doors” (93). He uses this form for a while, but later in the scene, when he comes to regard Roderigo as an ally, he shifts back to the polite you, beginning in line 163, “What said she to you?” and on to the end of the scene. For reasons not yet satisfactorily explained, Elizabethans used thou in addresses to God—“O God, thy arm was here,” the king says in Henry V (4.8.108)—and to supernatural characters such as ghosts and witches. A subtle variation occurs in Hamlet. When Hamlet first talks with the Ghost in 1.5, he uses thou, but when he sees the Ghost in his mother’s room, in 3.4, he uses you, presumably because he is now convinced that the Ghost is not a counterfeit but is his father.

Perhaps the most unusual use of pronouns, from our point of view, is the neuter singular. In place of our its, his was often used, as in “How far that little candle throws his beams.” But the use of a masculine pronoun for a neuter noun came to seem unnatural, and so it was used for the possessive as well as the nominative: “The hedge-sparrow fed the cuckoo so long / That it had it head bit off by it young.” In the late sixteenth century the possessive form its developed, apparently by analogy with the -s ending used to indicate a genitive noun, as in book‘s, but its was not yet common usage in Shakespeare’s day.

1 comment