The yellow lights of two tallow candles, pointed like spears, flickered on the table.

Uncle Jaakov grew more and more rigid, as though he were in a deep sleep with his teeth clenched; but his hands seemed to live with a separate existence. The bent fingers of his right hand quivered indistinctly over the dark keyboard, just like fluttering and struggling birds, while his left passed up and down the neck with elusive rapidity.

When he had been drinking he nearly always sang through his teeth in an unpleasantly shrill voice, an endless song:

"If Jaakove were a dog

He 'd howl from morn to night.

Oie! I am a-weary!

Oie! Life is dreary!

In the streets the nuns walk,

On the fence the ravens talk.

Oie! I am a-weary!

The cricket chirps behind the stove

And sets the beetles on the move.

Oie! I am a-weary!

One beggar hangs his stockings up to dry,

The other steals it away on the sly.

Oie! I am a-weary!

Yes! Life is very dreary!"

I could not bear this song, and when my uncle came to the part about the beggars I used to weep in a tempest of ungovernable misery.

The music had the same effect on Tsiganok as on the others; he listened to it, running his fingers through his black, shaggy locks, and staring into a corner, halfasleep.

Sometimes he would exclaim unexpectedly in a complaining tone, "Ah! if I only had a voice. Lord! how I should sing."

And grandmother, with a sigh, would say: "Are you going to break our hearts, Jaasha? . . . Suppose you give us a dance, Vanyatka?"

Her request was not always complied with at once, but it did sometimes happen that the musician suddenly swept the chords with his hands, then, doubling up his fists with a gesture as if he were noiselessly casting an invisible something from him to the floor, cried sharply:

"Away, melancholy! Now, Vanka, stand up!"

Looking very smart, as he pulled his yellow blouse straight, Tsiganok would advance to the middle of the kitchen, very carefully, as if he were walking on nails, and blushing all over his swarthy face and simpering bashfully, would say entreatingly:

"Faster, please, Jaakov Vassilitch!"

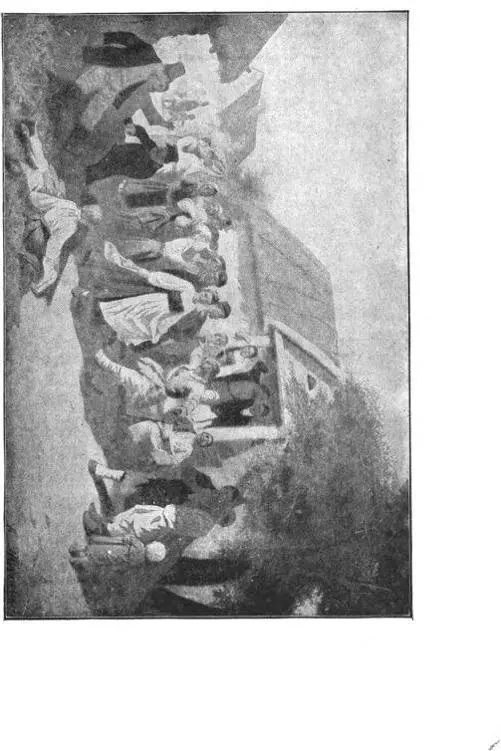

The guitar jingled furiously, heels tapped spasmodically on the floor, plates and dishes rattled on the table and in the cupboard, while Tsiganok blazed amidst the kitchen lights, swooping like a kite, waving his arms like the sails of a windmill, and moving his

feet so quickly that they seemed to be stationary; then he stooped to the floor, and spun round and round like a golden swallow, the splendor of his silk blouse shedding an illumination all around, as it quivered and rippled, as if he were alight and floating in the air. He danced unweariedly, oblivious of everything, and it seemed as though, if the door were to open, he would have danced out, down the street, and through the town and away . . . beyond our ken.

"Cross over!" cried Uncle Jaakov, stamping his feet, and giving a piercing whistle; then in an irritating voice he shouted the old, quaint saying:

"Oh, my! if I were not sorry to leave my spade

I 'd from my wife and children a break have made."

The people sitting at table pawed at each other, and from time to time shouted and yelled as if they were being roasted alive. The bearded chief workman slapped his bald head and joined in the uproar. Once he bent towards me, brushing my shoulder with his soft beard, and said in my ear, just as he might speak to a grown-up person:

"If your father were here, Alexei Maximitch, he would have added to the fun. A merry fellow he was--always cheerful. You remember him, don't you?"

"No."

"You don't? Well, once he and your grandmother --but wait a bit."

Tall and emaciated, somewhat resembling a conventional icon, he stood up, and bowing to grandmother, entreated in an extraordinarily gruff voice:

"Akulina Ivanovna, will you be so kind as to dance for us as you did once with Maxim Savatyevitch? It would cheer us up."

"What are you talking about, my dear man? What do you mean, Gregory Ivanovitch?" cried grandmother, smiling and bridling. "Fancy me dancing at my time of life! I should only make people laugh."

But suddenly she jumped up with a youthful air, arranged her skirts, and very upright, tossed her ponderous head and darted across the kitchen, crying:

"Well, laugh if you want to! And a lot of good may it do you. Now, Jaasha, play up!"

My uncle let himself go, and, closing his eyes, went on playing very slowly. Tsiganok stood still for a moment, and then leaped over to where grandmother was and encircled her, resting on his haunches, while she skimmed the floor without a sound, as if she were floating on air, her arms spread out, her eyebrows raised, her dark eyes gazing into space. She appeared very comical to me, and I made fun of her; but Gregory held up his finger sternly, and all the grown-up peopie looked disapprovingly over to my side of the room.

"Don't make a noise, Ivan," said Gregory, and Tsiganok obediently jumped to one side, and sat by the door, while Nyanya Eugenia, thrusting out her Adam's apple, began to sing in her low-pitched, pleasant voice:

"All the week till Saturday

She does earn what e'er she may,

Making lace from morn till night

Till she 's nearly lost her sight."

Grandmother seemed more as if she were telling a story than dancing. She moved softly, dreamily; swaying slightly, sometimes looking about her from under her arms, the whole of her huge body wavering uncertainly, her feet feeling their way carefully. Then she stood still as if suddenly frightened by something; her face quivered and became overcast . . . but directly after it was again illuminated by her pleasant, cordial smile. Swinging to one side as if to make way for some one, she appeared to be refusing to give her hand, then letting her head droop seemed to die; again, she was listening to some one and smiling joyfully . . . and suddenly she was whisked from her place and turned round and round like a whirligig, her figure seemed to become more elegant, she seemed to grow taller, and we could not tear our eyes away from her-- so triumphantly beautiful and altogether charming did she appear in that moment of marvelous rejuvenation. And Nyanya Eugenia piped:

"Then on Sundays after Mass

Till midnight dances the lass,

Leaving as late as she dare,

Holidays with her are rare."

When she had finished dancing, grandmother returned to her place by the samovar. They all applauded her, and as she put her hair straight, she said:

"That is enough! You have never seen real dancing. At our home in Balakya, there was one young girl--I have forgotten her name now, with many others--but when you saw her dance you cried for joy.

1 comment