The lawyers were clothed in sheep-skin, to remind them of the attributes of their calling—innocence, faithfulness, and sedateness. The repetition of their speeches was on account of the very slow apprehension and cautious decision of the people, by which peculiarities they were distinguished from all the inhabitants of the subterranean world. But what most excited my curiosity was the history of the supreme judge. This was a virgin, a native of the town, and appointed by the King to the office of Kaki, or judge, for her superior virtue and talent. It must be observed that this nation pay no regard to sex in appointments to office, but, after a strict examination, elect those to take charge of affairs who are proved to be the most worthy.

Seminaries are established throughout the country, to teach the aspirants to public honors the duties appertaining to the direction of government. The business of the administrators of these colleges is to search closely into the brains and hearts of the young students, and when satisfied with their virtue and ability, to give to the king a list of those fully prepared to fill the public offices. The administrators are called Karatti.

The young virgin of whom I have spoken, had received, four years before from the Karatti, a certificate for remarkable attainments and virtues, and had been invested with the "blanket." This blanket was wrapped about her head during my trial; this precaution, however, is taken only in trials such as mine, in which the occasionally broad nature of the testimony might have a painful effect upon the virgin judge, should her face be exposed to the public gaze.

The name of this virgin was Palmka. She had officiated for three years with the greatest honor, and was considered the most learned tree in the city.

She solved with so much discretion the knottiest questions, that her decisions had come to be regarded as oracles.

As Themis' self, with scales of equal weight,

She judged with candor both the small and great:

The sands of truth she, like the goddess, frees

From falsehood's glitter and from error's lees.

The following account was given to me of the blood-letting to which I had been subjected. When any one is proved to be guilty of a crime, he is bled, for the purpose of detecting from the color of the fluid, or blood, how far his guilt was voluntary or otherwise; whether he had sinned through malice or distemper. Should the fluid be found discolored, he is sent to the hospital to be cured; thus this process is rather a correction than a punishment. A member of the council, or any one high in office, would be removed, should it be found necessary to bleed him.

The reason why the surgeon, who performed the operation on me, was astonished, was, on account of the redness of my blood. The inhabitants having a sort of white fluid in their veins, the purity of which is proportional to their innocence and excellence.

I was put at my ease when I observed that the trees generally possessed a large share of humanity. This was displayed in their little attentions to me. Food was brought to me twice a day. It consisted of fruit and several kinds of beans; my drink was a clear, sweet and exceedingly delicious juice.

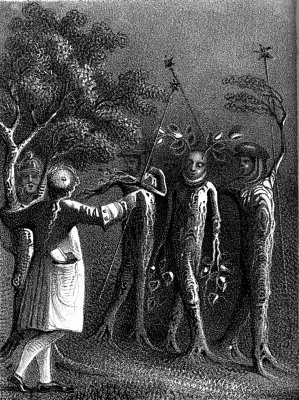

The sheriff, in whose house I was imprisoned, had immediately given notice to the King that he had by accident got possession of a somewhat sensible animal of an uncommon figure. The description of my person excited the king's curiosity. Orders were given to the sheriff, that I should be taught the language of the country; on which I should be sent to court. A teacher was appointed for me, whose instruction enabled me in a half year to speak very comprehensibly. After this preparatory course of private study, I was sent to the seminary, where particular care was taken both of my mental and physical education. Indeed, so enthusiastic were they to naturalize me, that they actually fastened branches to my body to make me look as much as possible like themselves.

CHAPTER III.

DESCRIPTION OF THE TOWN KEBA.

During the course of my education, my landlord frequently carried me about the town, and pointed out the most remarkable things. Keba is the town next in size and importance to the capital of the kingdom of Potu. The inhabitants are distinguished for their sedateness and moderation; old age is more respected by them than by any other community. They are strangely addicted to the pitting of animals against each other; or, as they call it, "play fight." I wondered that so moral a people could enjoy these brutal sports. My landlord noticed my surprise, and said, that throughout the kingdom it was the custom to vary their lives with a due mixture of earnest duties and amusing pleasures. Theatrical plays are very much in vogue with them. I was vexed, however, to hear that disputations are reckoned suitable for the stage, while with us they are confined to the universities.

At certain times in the year, disputants are set against each other, as we pit dogs and game cocks. High bets are made in favor of one or the other, and a premium is given to the winner.

Beside these disputants, who are called Masbakki, or boxers, various quadrupeds, wild as well as tame, are trained to fight as on our globe.

In this town a gymnasium is established, in which the liberal arts are taught with much success.

My landlord carried me, on a high festival day, to this academy. On this occasion a Madic, or teacher in philosophy, was elected. The candidate made a very prosy speech on some philosophical question, after which, without farther ceremony, he was entered, by the administrators, on the list of the public teachers.

On our way home from the academy, we met a criminal, led by three watchmen. By sentence of the kaki, he had been bled, and was now on his way to the city hospital. I inquired concerning his crime, and was answered, that he had publicly lectured on the being and qualities of God—a subject entirely forbidden in this country.

1 comment