" With these words he went over to

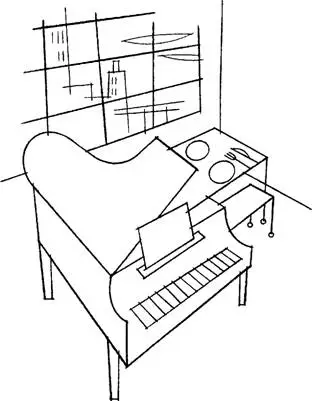

the piano, pressed a button, and there sprang forth—no other words were

adequate to the occasion—a table fitted with benches at which three guests

could sit with plenty of room.

"Very

ingenious, " Michel observed.

"Necessity

is our mother, " the pianist replied, "since the exiguity of the

apartments no longer permitted furniture! Have a look at this complex

instrument, an amalgamation of Érard and

Jeanselme[17]!

It fills every need, takes up no room at all, and I can assure you that the piano

itself is none the worse for it. "

At

this moment the doorbell rang. Quinsonnas opened the door and announced his

friend Jacques Aubanet, an employee of the General Corporation of Maritime

Mines. Michel and Jacques were introduced to each other in the simplest manner

possible.

Jacques

Aubanet, a handsome young man of twenty-five, was a close friend of Quinsonnas,

and like him reduced in circumstances. Michel had no idea what kind of work the

employees of the Corporation of Maritime Mines might do; certainly Jacques

brought with him a remarkable appetite.

Fortunately

dinner was ready; the three young men devoured: after

the initial moments of this struggle with comestibles, a few words managed to

make their way through the less expeditive mouthfuls. "My dear Jacques,

" Quinsonnas observed, "by introducing you to Michel Dufrénoy I

allowed you to make the acquaintance of a young friend who is one of us— one of

those poor devils Society refuses to employ according to their talents, one of

those drones whose useless mouths Society padlocks in order not to have to

feed!"

"Ah!

Monsieur Dufrénoy is a dreamer, " Jacques replied.

"A

poet, my friend! and I wonder what in the world he can be doing here in Paris,

where a man's first duty is to make money!"

"Obviously

enough, " Jacques replied, "he's landed on the wrong planet. "

"My

friends, " said Michel, "you're anything but encouraging, but I shall

take your exaggerations into account. "

"This

dear child, " Quinsonnas replied, "he hopes, he works, he loves good

books, and when Hugo, Musset, and Lamartine are no longer read, he hopes someone

will still read

him! But what have you done, wretch that

you are—have you invented a utilitarian poetry, a literature to replace

compressed air or power brakes? No? Well then! Gnaw your own vitals, my son! If

you don't have something sensational to tell, who will listen to you? Art is no

longer possible unless it produces a tour de force! These days, Hugo would have

to recite his

Orientates straddling two

circus horses, and Lamartine would perform his Harmonies upside

down from a trapeze!"

"Nonsense,

" exclaimed Michel, leaping up in indignation.

"Calm

down, child, " the pianist replied. "Just ask Jacques whether I'm

right or not. "

"A

hundred times over, " Jacques opined. "This world is nothing more

than a market, an immense fairground, and you must entertain your clients with

the talents of a mountebank. "

"Poor

Michel, " Quinsonnas continued with a sigh, "his Latin verse prize

will turn his head!"

"What

will you prove by that?" demanded the young man.

"Nothing,

my son! After all, you're following your destiny. You're a great poet! I've

seen some of your works; only you'll allow me to remark that they're hardly

suited to the taste of the age. "

"Which

means?"

"Which

means that you deal with poetical subjects, and nowadays that's a poetical

fault! You sing of mountains and valleys, fields and clouds, love and the

stars—all those worn-out things no one wants anymore!"

"Then

what should I sing?"

"Your

verses must celebrate the wonders of industry!"

"Never!"

Michel exclaimed.

"Well

put, " Jacques observed.

"For

instance, " Quinsonnas continued, "have you heard the ode that was

given first prize by the forty de Broglies cluttering up the Académie-Française?"

"No!"

"Well

then, listen and learn. Here are the two last stanzas:

And

coal was shoveled into blazing fires:

Through

glowing tubes the pressure it requires

Is

driven to the monster's heart; it pumps

In

pulsing fury and in frenzy thumps

Till,

bellowing, it emulates the forces

of

eighty horses!

Now

with his heavy bars, the engineer

Opens

the valves! Within the cylinder

The

double piston runs! The wheel has slipped

Its

cog! The roaring engine's speed is up!

The

whistle blows!... Hail to the Crampton System:

the

locomotive runs!

"Dreadful!"

Michel exclaimed.

"Some

nice rhymes, " Jacques observed.

"There

you are, my boy, " continued the pitiless Quinsonnas. "May heaven

keep you from being forced to live by your talent! Better follow the example of

those of us who recognize the present state of affairs for what it is, at least

until better days. "

"Is

Monsieur Jacques, " inquired Michel, "similarly obliged to ply some

rebarbative trade?"

"Jacques

is a shipping clerk in an industrial company, " Quinsonnas explained,

"which does not mean, to his great regret, that he has ever seen the

inside of a ship. "

"What

does it mean?" asked Michel.

"It

means, " Jacques replied, "that I'd have liked to be a soldier.

"

"A

soldier!" Michel betrayed his astonishment.

"Yes,

a soldier. A noble profession in which, barely fifty years ago, you could earn

an honest living!"

"Unless

you lost it even more honestly, " Quinsonnas added. "Well, it's over

and done with as a career, since there's no more army—unless you become a policeman.

In other times, Jacques would have entered some military academy, or joined up,

and there, after a life of battle, he would have become a general like a

Turenne, or an emperor like a Bonaparte! But nowadays, my handsome officer,

you'll have to give that all up. "

"Oh,

you never know!" said Jacques. "It's true that France, England,

Russia, and Italy have dismissed their soldiers; during the last century the

engines of warfare were perfected to such a degree that the whole thing had

become ridiculous—France couldn't help laughing—"

"And

having laughed, " Quinsonnas put in, "she disarmed. "

"Yes,

you joker! I grant you that with the exception of old Austria, the European

peoples have done away with the military state. But for all that, have they

done away with the spirit of battle natural to human beings, and the spirit of

conquest natural to governments?"

"Probably,

" remarked the musician.

"And

why?"

"Because

the best reason those instincts had for existing was the possibility of

satisfying them! Because nothing suggests battle so much as an armed peace, according

to the old expression! Because if you do away with painters there's no more

painting, sculptors, no more sculpture, musicians, no more music, and if you do

away with warriors—no more wars! Soldiers are artists. "

"Yes,

of course!" Michel exclaimed, "and rather than do the awful work I

do, I ought to join up. "

"Ah,

you fell for it, baby!" Quinsonnas crowed. "Is there any possibility

that you'd like to fight?"

"Fighting

ennobles the soul, " Michel replied, "at least according to Stendhal,

one of the great thinkers of the last century."

"Yes,

it does, " the pianist agreed, but added, "How much brains does it

take to give a good thrust with a saber?"

"A

lot, if you're going to do it right, " Jacques answered.

"And

even more, if you're going to receive the thrust, " Quinsonnas retorted.

"My word, my friends, it's likely you're right, from a certain point of

view. Perhaps I'd be inclined to make you a soldier, if there was still an

army; with a little philosophy, it's a fine career. But nowadays, since the

Champs-de-Mars has been turned into a school, we must give up fighting.

1 comment