Nonetheless, since

everything—even speeches—must come to an end, the machine stopped. The

oratorical exercises having been terminated without incident, the Ceremony

proceeded to the actual awarding of the prizes.

The

question given to the Grand Competition of Higher Mathematics was as follows:

Given two circumferences OO': from a point A on O, tangents are drawn to O';

the contact points of these tangents are joined: the tangent at A is drawn to

the circumference O; what is the point of intersection of this tangent with the

chord of contacts in the circumference O'?

The

importance of such a theorem was universally understood. Many were familiar

with how it had been solved according to a new method by the student Gigoujeu

(François Némorin) from Briançon (Hautes

Alpes). Bravos rang out when this name was called; it was uttered seventy-four

times in the course of this memorable day: benches were broken in honor of the

laureate, an activity which, even in 1960, was not yet merely a metaphor

intended to describe the outbreaks of enthusiasm.

On this

occasion Gigoujeu (François Némorin) was

awarded a library of some three thousand volumes. The Academic Credit Union did

things properly.

We

cannot cite the endless nomenclature of the Sciences which were taught in this

barracks of learning: an honors list of the day would have certainly astonished

the great-grandfathers of these young scholars. The prize giving continued, and

jeers rang out when some poor devil from the Division of Letters, shamed when

his name was called, received a prize in Latin composition or an honorable

mention for Greek translation. But there came a moment when the taunts

redoubled, when sarcasm assumed its most disconcerting forms. This was when

Monsieur Frappeloup pronounced the following words:

"First

prize for Latin verse: Dufrénoy (Michel Jérome)

from Vannes (Morbihan). "Hilarity was universal, amid remarks of this

sort:

"A

prize for Latin verse!"

"He

must have been the only competitor!"

"Look

at that darling of the Muses!"

"A

habitue of Helicon!"

"A

pillar of Parnassus!" et cetera, et cetera.

Nonetheless,

Michel Jérome Dufrénoy stepped forward and

faced down his detractors with a certain aplomb; he was a blond youth with a

delightful countenance and a charming manner, neither awkward nor insolent.

His long hair gave him a slightly girlish appearance, and his forehead shone

as he advanced to the dais and snatched rather than received his prize from the

Director's hand. This prize consisted of a single volume: the latest Factory Manual.

Michel

glanced scornfully at the book and, flinging it to the ground, calmly returned

to his seat, still wearing his crown and without even having kissed His

Excellency's official cheeks.

"Well

done, " murmured Monsieur Richelot.

"Brave

boy, " said Monsieur Huguenin.

Murmurs

broke out on all sides. Michel received them with a disdainful smile and sat

down amid the cat-calls of his schoolfellows.

This

grand ceremony concluded without hindrance around seven in the evening; fifteen

thousand prizes and twenty-seven thousand honorable mentions were distributed.

The chief laureates of the Sciences dined that same evening at Baron de

Vercampin's table, among members of the Administrative Council and the major

stockholders.

The joy

of these latter was explained by... figures! The dividend for the 1960

exercises had been set at 1, 169 francs, 33 centimes per share. The current interest

already exceeded the issue price.

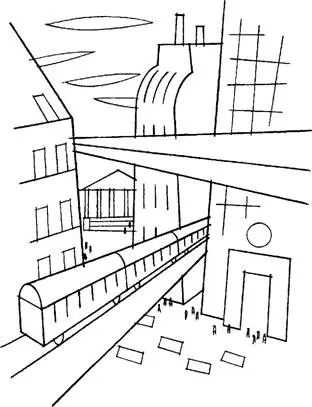

Chapter II: A Panorama of the Streets of Paris

Michel

Dufrénoy had followed the crowd, a mere drop of water in this stream

transformed into a torrent by the removal of its obstructions. His excitement

had subsided; the champion of Latin poetry became a timid young man amid this

joyous throng; he felt alone, alien, and somehow isolated in the void. Where

his fellow students hurried ahead, he made his way slowly, hesitantly, even

more orphaned in this gathering of contented parents; he seemed to regret his

labors, his school, his professor.

Without

father or mother, he would now have to return to an unsympathetic household,

certain of a grim reception for his Latin verse prize. "All right, "

he resolved, "let's get on with it! I shall endure their nastiness along

with all the rest! My uncle is a literal-minded man, my aunt a practical woman,

and my cousin a boy out for the main chance—ideas like mine are not welcome at

home, but so what? Onward!"

Yet he

proceeded quite unhurriedly, not being one of those schoolboys who rush into

vacation like a subject people into freedom. His uncle and guardian had not

even thought enough of the occasion to attend the prize giving; he knew what

his nephew was "incapable" of, as he said, and would have been

mortified to see him crowned a nursling of the Muses.

The

crowd, however, impelled the wretched laureate forward; he felt himself borne

on by the current like a drowning man. "A good comparison, " he

thought. "Here I am abandoned on the high seas; requiring the talents of a

fish, all I have are the instincts of a bird; I want to live in space, in the

ideal regions no longer visited—the land of dreams from which one never returns!"

Amid

such reflections, jostled and buffeted, he reached the Grenelle station of the

Metro. This line served the Left Bank of the river along the Boulevard Saint-Germain,

which extended from the Gare d'Orléans to

the buildings of the Academic Credit Union; here, curving toward the Seine, it

crossed the river on the Pont d'Iéna,

utilizing an upper level reserved for the railroad, and then joined the Right

Bank line, which, through the Trocadéro

tunnel, reached the Champs-Élysées and the axis of the Boulevards, which it

followed to the Place de la Bastille, crossing the Pont d'Austerlitz to rejoin

the Left Bank line.

This

first ring of railroad tracks more or less encircled the ancient Paris of

Louis XV, on the very site of the wall survived by this euphonious verse:

Le mur murant Paris rend Paris

murmurant.

A second line reached the old faubourgs of Paris, extending

for some thirty-two kilometers neighborhoods formerly located outside the

peripheral boulevards. A third line followed the old orbital roadway for a

length of some fifty-six kilometers. Finally, a fourth system connected the

line of fortifications, its extent more than a hundred kilometers.

It is

evident that Paris had burst its precincts of 1843 and made incursions into the

Bois de Boulogne, the Plains of Issy, Vanves, Billancourt, Montrouge, Ivry,

Saint-Mandé, Bagnolet, Pantin, Saint-Denis, Clichy, and Saint-Ouen. The heights

of Meudon, Sevres, and Saint-Cloud had blocked its development to the west. The

delimitation of the present capital was marked by the forts of Mont Valérien,

Saint- Denis, Aubervilliers, Romainville, Vincennes, Charenton, Vitry, Bicêtre, Montrouge, Vanves, and Issy; a city of

one hundred and five kilometers in diameter, it had devoured the entire

Department of the Seine.

Four

concentric circles of railways thus formed the Metropolitan

network; they were linked to one another by branch lines, which, on the Right

Bank, extended the Boulevard de Magenta and the Boulevard Malesherbes and on

the Left Bank, the Rue de Rennes and the Rue des Fosses-Saint-Victor. It was

possible to circulate from one end of Paris to the other with the greatest

speed.

These

railways had existed since 1913; they had been built at State expense,

following a system devised in the last century by the engineer Joanne[3]. At that time, many

projects were submitted to the Government, which had them examined by a

council of civil engineers, those of the Ponts et Chausées no longer existing

since 1889, when the École Polytechnique had been suppressed; but this council

had long remained divided on the question; some members wanted to establish a

surface line on the main streets of Paris; others recommended underground

networks following London's example; but the first of these projects would

have required the construction of barriers protecting the train tracks, whence

an obvious encumbrance of pedestrians, carriages, carts, et cetera; the second

involved enormous difficulties of execution; moreover, the prospect of even

temporary burial in an endless tunnel was anything but attractive to the

riders. Every roadway formerly created under these deplorable conditions had

had to be remade, among others the Bois de Boulogne line, which by both bridges

and tunnels compelled riders to interrupt reading their newspapers

twenty-seven times during a trajectory of some twenty-three minutes.

Joanne's

system seemed to unite all the virtues of rapidity, facility, and comfort, and

indeed for the last fifty years the Metropolitan railways had functioned to

universal satisfaction.

This

system consisted of two separate roadbeds on which the trains proceeded in

opposite directions; hence there was no possibility of a collision. Each of

these tracks was established along the axis of the boulevards, five meters

from the housefronts, above the outer rim of the sidewalks; elegant columns of

galvanized bronze supported them and were attached to one another by cast

armatures; at intervals these columns were attached to riverside houses, by

means of transverse arcades. Thus, this long viaduct, supporting the railway

track, formed a covered gallery, under which strollers found shelter from the

elements; the asphalt roadway was reserved for carriages; by means of an

elegant bridge the viaduct traversed the main streets which crossed its path,

and the railway, suspended at the height of the mezzanine floors, offered no

obstacle to boulevard traffic.

Some

riverside houses, transformed into waiting rooms, formed stations which

communicated with the track by broad footbridges; underneath a double-ramp

staircase gave access to the waiting room. Boulevard stations were located at

the Trocadéro, the Madeleine, the Bonne Nouvelle department store, the Rue du

Temple, and the Place de la Bastille.

This

viaduct, supported on simple columns, would doubtless not have resisted the old

means of traction, which required locomotives of enormous weight; but thanks to

the application of new propulsors, the modern trains were quite light; they

ran at intervals of ten minutes, each one bearing some thousand riders in its

comfortably arranged cars.

The

riverside houses suffered from neither steam nor smoke, quite simply because

there was no locomotive: the trains ran by means of compressed air, according

to the Williams System, recommended by the famous Belgian engineer Jobard[4], who flourished in the

mid-nineteenth century.

A vector

tube some twenty centimeters in diameter and two millimeters thick ran the

entire length of the track between the two rails; it enclosed a soft-iron disc,

which

slid inside it under the action of several atmospheres of compressed air

provided by the Catacomb Company of Paris.

1 comment