The earlier pages of the volume have been given up to a “Sketch of the History of Political Economy,” which aims to give the story of how we have arrived at our present knowledge of economic laws. The student who has completed Mill will then have a very considerable bibliography of the various schools and writers from which to select further reading, and to select this reading so that it may not fall wholly within the range of one class of writers. But, for the time that Mill is being first studied, I have added a list of the most important books for consultation. I have also collected, in Appendix I, some brief bibliographies on the Tariff, on Bimetallism, and on American Shipping, which may be of use to those who may not have the means of inquiring for authorities, and in Appendix II a number of questions and problems for the teacher's use.

In some cases I have omitted Mr. Mill's statement entirely, and put in its stead a simpler form of the same exposition which I believed would be more easily grasped by a student. Of such cases, the argument to show that Demand for Commodities is not Demand for Labor, the Doctrine of International Values, and the Effect of the Progress of Society on wages, profits, and rent, are examples. Whether I have succeeded or not, must be left for the experience of the teacher to determine. Many small figures and diagrams have been used throughout the text, in order [pg vi] to suggest the concrete means of getting a clear grasp of a principle.

In conclusion, I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to several friends for assistance in the preparation of this volume, among whom are Professor Charles F. Dunbar, Dr. F. W. Taussig, Dr. A. B. Hart, and Mr. Edward Atkinson.

J. Laurence Laughlin.

Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts,

September, 1884.

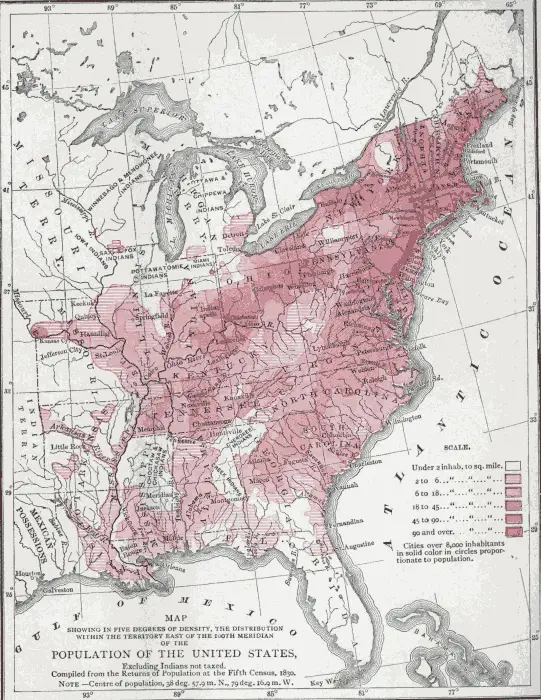

Chart I

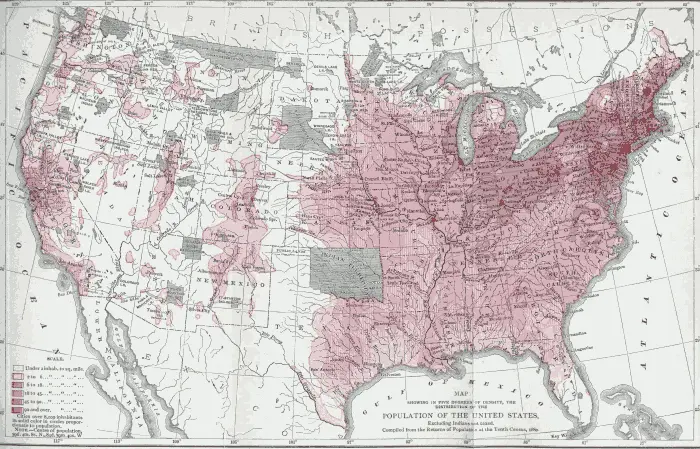

Chart II

[pg 001]

Introductory.

A Sketch Of The History Of Political Economy.

General Bibliography.—There is no satisfactory general history of political economy in English. Blanqui's “Histoire de l'économie politique en Europe” (Paris, 1837) is disproportioned and superficial, and he labors under the disadvantage of not understanding the English school of economists. He studies to give the history of economic facts, rather than of economic laws. The book has been translated into English (New York, 1880).

Villeneuve-Bargemont, in his “Histoire de l'économie politique”(Paris, 1841), aims to oppose a “Christian political economy” to the “English” political economy, and indulges in religious discussions.

Travers Twiss, “View of the Progress of Political Economy in Europe since the Sixteenth Century” (London, 1847), marked an advance by treating the subject in the last four centuries, and by separating the history of principles from the history of facts. It is brief, and only a sketch. Julius Kautz has published in German the best existing history, “Die geschichtliche Entwickelung der National-Oekonomie und ihrer Literatur” (Vienna, 1860). (See Cossa, “Guide to the Study of Political Economy,” page 80.) Cossa in his book has furnished a vast amount of information about writers, classified by epochs and countries, and a valuable discussion of the divisions of political economy by various writers, and its relation to other sciences. It is a very desirable little hand-book. McCulloch, in his “Introduction to the Wealth of Nations,” gives a brief sketch of the growth of economic doctrine. The editor begs to acknowledge his great indebtedness for information to his colleague, Professor Charles F. Dunbar, of Harvard University.

Systematic study for an understanding of the laws of political economy is to be found no farther back than the [pg 002] sixteenth century. The history of political economy is not the history of economic institutions, any more than the history of mathematics is the history of every object possessing length, breadth, and thickness. Economic history is the story of the gradual evolution in the thought of men of an understanding of the laws which to-day constitute the science we are studying. It is essentially modern.1

Aristotle2 and Xenophon had some comprehension of the theory of money, and Plato3 had defined its functions with some accuracy.

1 comment