We had felt for some time that our improvised restaurant encampment under the auspices of distant stars was doomed to collapse miserably, unequal to the ever increasing demands of the night. What could we set against these bottomless wastes? The night simply canceled our human undertaking, even though it was supported by the sound of the violins, and moved into the gap, shifting its constellations to their rightful positions.

We looked at the disintegrating camp of tables, the battlefield of half-folded tablecloths and crumpled napkins, across which the night trod in triumph, luminous and immense. We got up as well, and our thoughts, forestalling our bodies, followed the movements of starry carts on their great and shiny paths.

And so we walked off under the stars, anticipating with half-closed eyes the ever more splendid illuminations. Ah, the cynicism of such a triumphant night! Having taken possession of the whole sky, it now played dominoes in space, lazily and without calculation, indifferently losing or winning millions. Then, bored, it traced on the battlefield of overturned tiles transparent squiggles, smiling faces, the same smile in a thousand copies, which a moment later rose toward the stars, already eternal, and dispersed into starry indifference.

On our way home we stopped at a pastry shop to get cakes. No sooner had we entered the white, icing sugar room than the night suddenly tensed up and became watchful lest we should escape. It waited for us patiently, outside the door, showing the unmoving stars through the window panes of the shop while we were inside selecting our cakes with great deliberation.

It was then that I saw Bianca for the first time. She stood sideways in front of the counter with her governess; she was slim and linear in a white dress as if she had just left the zodiac. She did not turn her head but stood with the perfect poise of a young girl, eating a cream bun. I could not see her clearly, for the zigzags of starry lines still lingered under my eyelids. It was the first time that our still confused horoscopes had crossed, met, and dissolved in indifference. We did not anticipate our fate from that early aspect of the stars, and we left the shop casually, making the glass-fronted door rattle.

The photographer, my father and I walked home in a roundabout way, through distant suburbs. The few houses there were small, and eventually houses disappeared altogether. We entered a climate of gentle warm spring; the silvery reflection of a young, violet moon just risen crept on the muddy path. That pre-spring night antedated itself, feverishly anticipating its later phases. The air, a short while before seasoned with the usual tartness of the time of year, became sweetly insipid, filled with the smell of rain, of damp loam, and of the first snowdrops that bloomed spectrally in the white, magic light. And it was strange that under that benevolent moon frogs' spawn did not spread on the silvery mud, that the night did not resound with a thousand gossiping mouths on those graveled river banks saturated with shiny drops of sweet water. And one had to imagine the croaking of frogs in the night, which was filled with the murmur of subterranean springs, so that—after a moment of stillness—the moon might continue on its way and climb higher in the sky, spreading wide its whiteness, ever more luminous, more magical and transcendental.

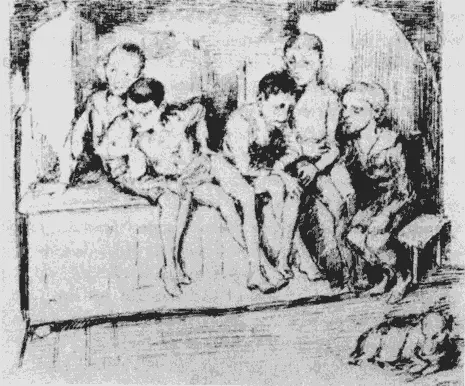

We walked thus under the waxing moon. My father and the photographer half-carried me between them, for I was stumbling with tiredness and hardly able to walk. Our steps crunched in the moist sand. It had been a long time since I had slept while walking, and under my eyelids I now saw the whole phosphorescence of the sky, full of luminous signs, of signals and starry phenomena. At last we reached an open field. My father laid me down on a coat spread on the ground. With closed eyes I saw the sun, the moon, and eleven stars aligned in the sky and parading before me.

"Bravo, Joseph!" my father exclaimed and clapped his hands in praise. I committed an unconscious plagiarism of another Joseph and the circumstances were not the same, but no one held it against me. My father, Jacob, shook his head and smacked his lips, and the photographer stood his tripod on the sand, pulled out his camera like a concertina, and hid himself entirely in the folds of its black cloth: he was photographing the strange phenomenon, a shining horoscope in the sky, while I, my head swimming in brightness, lay blinded on the ground and limply held up my dream to exposure.

III

The days became long, light, and spacious—maybe too spacious for their content, which was still poor and tenuous. They were days with an allowance for growth, days pale with boredom and impatience and full of waiting. A light, bright breeze cut their emptiness, yet untroubled by the exhalations of the bare and sunny gardens; it blew the streets clean, and they looked long and festively swept, as if waiting for someone's announced but uncertain arrival. The sun headed for the equinoctial position, then braked and almost reached the point at which it would seem to stand immobile, keeping an ideal balance and throwing out streams of fire, wave after wave, onto the empty and receptive earth.

A continuous draft blew through the whole breadth of the horizon, creating avenues and lanes. It calmed itself while blowing and stopped at last, breathless, enormous and glassy as if wishing to enclose in its all-embracing mirror the ideal picture of the city, a Fata Morgana magnified in the depth of its luminous concavity.

1 comment