Suite Francaise

Suite Française

Irène Némirovsky

Translated by Sandra Smith

ALFRED A. KNOPF NEW YORK • TORONTO

2006

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

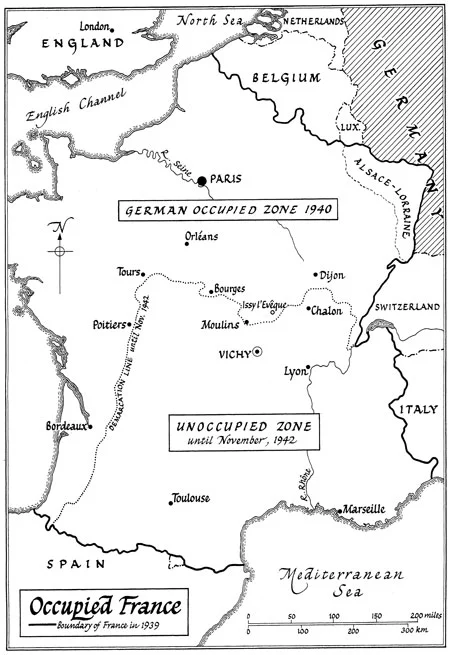

Map

Translator’s Note

ONE

Storm in June

1

War

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

TWO

Dolce

1

Occupation

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Appendices

APPENDIX I

Irène Némirovsky’s handwritten notes on the situation in France and her plans for Suite Française, taken from her notebooks

APPENDIX II

Correspondence 1936–1945

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

Preface to the French Edition

Copyright Page

I dedicate this novel to the memory of my mother and father, to my sister, Elisabeth Gille, to my children and grandchildren, and to everyone who has felt and continues to feel the tragedy of intolerance.

—DENISE EPSTEIN

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

Irène Némirovsky wrote the two books that form Suite Française under extraordinary circumstances. While they may seem remarkably polished and complete, “Storm in June” and “Dolce” were actually part of a work-in-progress. Had she survived, Irène Némirovsky would certainly have made corrections to these two books and completed the cycle she envisaged as her literary equivalent to a musical composition.

Translation is always a daunting task, especially when the translator has so much respect and affection for the author. It is also a creative task that often requires “leaps of faith”: a feeling for tone, sensing the author’s intention, taking the liberty to interpret and, sometimes, to correct. With Suite Française, I have made slight changes in order to correct a few minor errors that appear in the novel. In particular, I have altered characters’ names when they were inconsistent and could prove confusing. However, I have retained other anomalies that pose no real problem to the reader, such as the incorrect proximity of Tours to Paray-le-Monial. Perhaps the most striking error for the English reader is the misquotation of Keats, when Némirovsky writes: “This thing of Beauty is a guilt for ever.” I have deliberately retained this mistake in the text as a poignant reminder that Némirovsky was writing Suite Française in the depths of the French countryside, with a sense of urgent foreboding and nothing but her memory as a source.

The Appendices in this edition provide important details regarding Némirovsky’s plans for the remaining three books, along with poignant correspondence that reveals her own family’s terrible situation.

This translation would not have been possible without the support, advice and encouragement of many people. I am very grateful to my husband Peter, my son Harry, Rebecca Carter at Chatto & Windus, Anne Garvey, Patricia Freestone, Philippe Savary, Paul Micio, Jacques Beauroy and my friends and colleagues at Robinson College, Cambridge. It has been a privilege to translate Suite Française. I am sure Irène Némirovsky would have been happy that so many years after her tragic murder, so many thousands world wide can once again hear her voice. I hope I have done her justice.

I wish to dedicate this translation to my family: the Steins, Lantzes, Beckers and Hofstetters, and to all the countless others who fought, and continue to fight, prejudice and persecution.

ONE

Storm in June

1

War

Hot, thought the Parisians. The warm air of spring. It was night, they were at war and there was an air raid. But dawn was near and the war far away. The first to hear the hum of the siren were those who couldn’t sleep—the ill and bedridden, mothers with sons at the front, women crying for the men they loved. To them it began as a long breath, like air being forced into a deep sigh. It wasn’t long before its wailing filled the sky. It came from afar, from beyond the horizon, slowly, almost lazily. Those still asleep dreamed of waves breaking over pebbles, a March storm whipping the woods, a herd of cows trampling the ground with their hooves, until finally sleep was shaken off and they struggled to open their eyes, murmuring, “Is it an air raid?”

The women, more anxious, more alert, were already up, although some of them, after closing the windows and shutters, went back to bed. The night before—Monday, 3 June—bombs had fallen on Paris for the first time since the beginning of the war. Yet everyone remained calm. Even though the reports were terrible, no one believed them. No more so than if victory had been announced. “We don’t understand what’s happening,” people said.

They had to dress their children by torchlight. Mothers lifted small, warm, heavy bodies into their arms: “Come on, don’t be afraid, don’t cry.” An air raid. All the lights were out, but beneath the clear, golden June sky, every house, every street was visible. As for the Seine, the river seemed to absorb even the faintest glimmers of light and reflect them back a hundred times brighter, like some multifaceted mirror. Badly blacked-out windows, glistening rooftops, the metal hinges of doors all shone in the water.

1 comment