The later version of the novel also introduces specific Homeric devices that help elevate the novel’s action, such as extended metaphors, the cataloging of the heroes’ names, and similes that retard the action at crucial moments and heighten the tension. In one instance, Gogol describes Taras Bulba’s heroic son Ostap at a critical moment on the battlefield to be “like a hawk flying wide circles high in the sky, its powerful wings spread wide, stopping suddenly before plummeting like an arrow at the quail squealing in terror.” While in the Iliad, Homer describes Hector attacking Achilles “like a hawk which hovers awhile over some lofty cliff, then darts to earth after a bird.”1

Within the epic scope of Taras Bulba, Gogol presents a detailed picture of the structure and principles of the Sech (the fortified Cossack encampment) on an island in the river Dnieper. Gogol’s description of the structure of the Sech is detailed and realistic, though historians have pointed out that he brought together historical elements from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for literary effect. This adds to the timeless quality of Taras Bulba, which is set, as Robert Kaplan points out in his Introduction, “sometime between the mid-sixteenth and seventeenth century.”

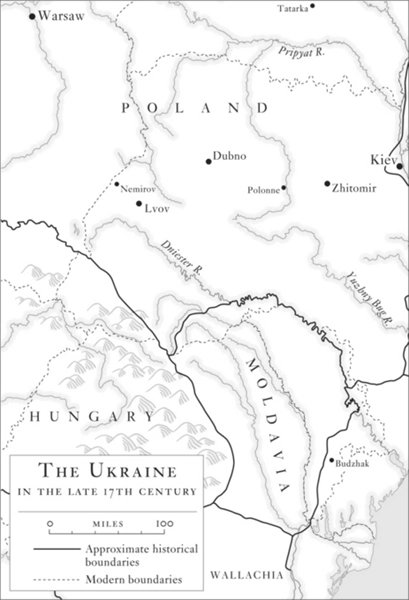

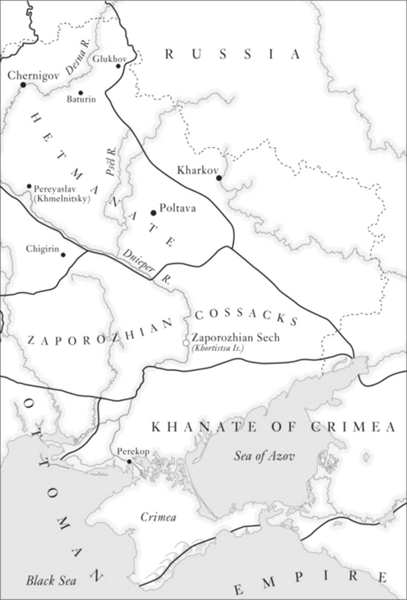

The Cossacks were the descendants of disenfranchised Russians who, during the reign of Ivan the Great (1440–1505), migrated to the Ukraine in search of freedom during “the gathering of the lands”—Ivan’s subjugation of the principalities surrounding Moscow to form a greater Muscovy. Over the next centuries, the Cossack communities fought for their continued independence, making their own laws and electing their own chiefs and commanders. By the mid-sixteenth century there were two large Cossack strongholds: one was on the river Don, the other was the Zaporozhian Sech on the Dnieper.

In the Zaporozhian Sech, unmarried Cossacks lived in fortified barracks from which women were excluded, while their married comrades—like Taras Bulba—lived in homesteads outside the Sech. The married Cossacks would regularly come to the Sech to join the Cossack army on campaigns and raids. Each year an assembly consisting of every adult Cossack elected a council of commanders to run the community’s affairs and to choose a leader, the Ataman. As Gogol shows, the Ataman’s powers were absolute during times of war, though the Ataman did convene assemblies to decide on important strategies. The assembly based its decisions on which Cossack faction shouted the loudest. Sometimes violence broke out during the voting.

The presence of the warring Cossacks on the western steppes of the Ukraine unsettled both the Polish and the Muscovite governments. Both tried to gain influence over the Cossacks by registering them, which made them subject to military duty. Taras Bulba “loved the simple life of the Cossack, and quarreled with comrades who were drawn to the Warsaw faction, accusing them of being lackeys of the Polish noblemen.”

Gogol modeled Taras Bulba on Bogdan Khmelnitsky (1595–1657), who was Ataman of the Zaporozhian Cossacks from 1648 to 1657, and who organized a rebellion against Polish rule in the Ukraine that ultimately led to the transfer of the Ukrainian lands east of the Dnieper to Russian control.

In Taras Bulba, Gogol made the Cossacks the emblem of the Russian spirit:

[T]he whole of primitive Russia’s south, abandoned by its princes, was laid waste and left in ruins by the relentless onslaught of the Mongol marauders; it was a time when man, turned out of house and home, became dauntless, when he settled in charred ruins in the face of terrible neighbors and never-ending danger, learning to look them in the eye and unlearning that fear exists in the world; when the flames of war gripped the ancient peaceful Slavic spirit, and Cossackry—that wide, raging sweep of Russian character—was introduced.… It was truly an extraordinary phenomenon of Russian power, arising from the national heart of fiery poverty.

The style of Taras Bulba is unlike anything Gogol wrote before or after. The expansive epic tone is quite different from the sharp and witty social critique of his later works, such as Dead Souls or “The Overcoat.” One of the major tasks facing this translator was to fathom and reflect Gogol’s rendition of Cossack speech in its simplicity and directness, speech that nevertheless harbors a noble grandeur. Gogol’s Cossacks are men of war who best express themselves in the violence of battle, and yet when they do speak, their words have an epic weight. I was fortunate to be able to rely on my Russian editor, Katya Ilina, who is of Cossack background and who was able to explain many details and nuances. I am thankful for the many hours she spent checking the text.

I would also like to express my thanks to MJ Devaney, my editor at Modern Library, and to my agent, Jessica Wainwright, whose interest in Russian literature has been a source of great encouragement over the years.

My very special thanks to Burton Pike, who introduced me to the pleasures of translation and who provided much advice and support throughout the project.

1. The Iliad, translated by W.H.D. Rouse (New York, 1960), p. 150.

TARAS BULBA

1

“Turn around and let me look at you! What a sight! What are you wearing there, a priest’s cassock or something? Is that how you run around at that academy of yours?”

These were the words with which old Bulba greeted his two sons, who, having completed their studies at the Seminary in Kiev, had come home to their father. The sons had just dismounted from their horses. They were robust young men, with the sullen look one sees in all Seminary students recently released. Their strong, healthy faces were covered with a first down that had not yet been touched by a razor. Embarrassed by the way their father welcomed them, they stared sullenly at the ground.

“Wait, wait! Let me get a good look at you!” Bulba continued, turning them around. “What are these long tunics you’re wearing, if you can even call them that? I’ve never seen the like! Take a few steps—I swear they’ll get caught between your legs, and you’ll go flying!”

“Don’t make fun of us, Papa!” the older of the boys finally said.

“Look how high and mighty he is! And why, pray, shouldn’t I make fun of you?”

“Because, well … even though you’re my papa, if you make fun of me, then by God I’ll thrash you!”

“Ha! You damn son of a you-know-what! Your own father?” Taras Bulba shouted, staggering back in surprise.

“Yes, even though you’re my father. Insult me, and I don’t care who you are!”

“So how do you want to fight, with your fists?”

“Any way you want!”

“Well then, show me your fists!” Taras Bulba said, pulling up his sleeves. “I’d like to see what kind of man you are with your fists!”

Father and son, instead of greeting one another after their long separation, began throwing punches at each other’s stomach and chest, stepping back to glare at each other and then attacking again.

“Neighbors, villagers!” shouted the boys’ pale, gaunt mother, who was standing on the threshold and had not had a chance to embrace her beloved children. “The old man’s gone mad! His mind’s unhinged! The boys come home, we haven’t seen them for over a year, and what does he do? Fly at them with his fists!”

“He fights well, this one!” Bulba gasped, stopping for a moment. “By God, he fights well!” he continued, catching his breath. “So well that I’d have done better not to test him. He’ll make a good Cossack, this one! I welcome you, my son! Let us kiss!”

And father and son kissed.

“Well done, my boy! You can get the better of any man if you go at him the way you went at me! Show mercy to no one.

1 comment